Journal of Scientific Exploration,Vol. 4, No.2, pp. 171-188, 1990

Moslem Cases of the Reincarnation Type in Northern India:

A Test of the Hypothesis of Imposed Identification

Part I: Analysis of 26 Cases

ANTONIA MILLS

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry and Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908

Abstract- The author describes the features of 26 Moslem (or half-Moslem) cases of the reincarnation type in India. In eight of these cases a Moslem child is said to have recalled the life of a Moslem. In seven cases a Moslem child is said to have recalled a life as a Hindu, and in 11 cases a Hindu child is said to have recalled the life of a Moslem (these are referred to as half-Moslem cases). Most Moslems in India do not officially endorse the concept of human earthly reincarnation. In some instances the absence of the doctrine in Islam made Moslems hostile to investigation of the cases. However, the cases are generally very similar to the more common Hindu cases, except that in solved Moslem and half-Moslem cases a higher proportion of previous personalities died violently, and the subjects in the half-Moslem cases showed behavior and (in two instances) birthmarks appropriate for the other religious community. Both Hindu and Moslem parents found it troubling to have a child recall a past life in a different religion. Such cases are unlikely to be the result of subtle clues given the child to adopt an envied identity.

Introduction

The majority of the numerous cases Stevenson (1966, 1969, 1974, 1975a, 1975b, 1977, 1980, 1983b, 1985, 1986, 1987) has reported of children who are said to remember a previous life occur in cultures that believe in reincarnation, such as the Hindu and Buddhist cultures of South Asia and various tribal peoples from a number of continents. The incidence of reported cases (Stevenson, 1983a, 1987) is, not surprisingly, smaller among the Sunni Moslem and Judeo-Christian populations, which do not believe in reincarnation.

Stevenson (1966, 1980) has reported many cases among the Druze of Lebanon and the Alevi of Turkey, two Shi'ite Moslem communities that believe in reincarnation, but no cases among the Sunni Moslem population, which does not endorse the concept that a human being comes back for a second or repeated earthly reincarnations.

In the majority of the more than 2,400 cases of the reincarnation type on file at the Division of Personality Studies at the University of Virginia, the child and the person he/she is said to recall being are from the same culture and country. Stevenson (1987) has noted that there are a small number of "international cases" in which a child recalls a life in another culture and country, but in these cases no one has been found to correspond to the child's description.

During 1987-1989 I undertook three trips to India to conduct, at the invitation of Ian Stevenson, an independent replication study of his investigations into cases in which a child is said to spontaneously remember a previous life. After the first trip I recognized that the Moslem cases in India would be of particular interest, because such cases would be unlikely to be encouraged or coached by parents. I therefore investigated five such cases (and one possibly spurious case reported in Part I1of this paper). These five cases had previously been investigated by Stevenson and Pasricha. The sixth case, possibly spurious, was previously unstudied.

This paper describes the characteristics of 26 cases of the reincarnation type within India in which a Moslem child claimed to recall a past life (either as a Moslem or a Hindu) or a Hindu child claimed to recall a life as a Moslem. I refer to the cases in which both the subject and the previous personality were Moslem as "Moslem cases." Cases in which either the sub- ject or the previous personality were Moslem but the other person was Hindu are referred to as "half-Moslem"cases. The features of these Moslem and half-Moslem cases are compared to the features of the more frequent Hindu to Hindu cases in India reported by Stevenson (1974, 1975b)and his colleagues (Cook, Pasricha, Samararatne, U Win Maung, & Stevenson, 1983; Pasricha, 1990; Stevenson, 1986) and studied by myself (Mills, 1989).'

These intercultural or interreligious cases are of particular interest for several reasons. First, they offer an opportunity to discern whether the identification of a child with another religious group was the result of mimicking or role modelling for the child's religious group behavior, and therefore provide a test of whether status-envy identification (Burton & Whiting, 1961) can provide an adequate explanation for the phenomenon. Second, such cases allow evaluation of another alternative explanation, suggested by Brody (1979)' according to which children who remember a past life are in fact adopting an alternate identity in response to subtle cues from the socializers who, perhaps unconsciously, encourage such an identity formation.

In Part II of this paper I present the data from three Moslem or half-Moslem.. so that the readers can assess on what basis the Moslem and Hindu community identify such cases and can decide for themselves whether the cases suggest that some paranormal phenomenon may be taking place.

Relevant Relationships Between Moslems and Hindus in India

Belief in reincarnation was presumably almost universal in India at the time of the successive Moslem contacts and conquests in India (Haimendorf, 1953; Obeyesekere, 1980; O'Flaherty, 1980). Mohammed (571-623 A.D.), the Prophet and founder of Islam, expressed the prevalent Semitic view of his time that a human had only one life on earth. Dissension over the proper succession of leadership in Islam led to the formation of two separate sects, the Sunni or orthodox Moslems, and the Shiite sects. From the earliest times the Moslems who have come to India have represented the variety of Islamic thought, both Sunni and Shiite (Hodgson, 1974; Hollister, 1953). However, none of the Moslem groups in India, whether they were Sunni, Shiite, or the Shiite mystical Sufi groups, ever officially endorsed the concept of reincarnation (Schimmel, 1975). Moslem rulers varied in their tolerance, intolerance, and interest in Hindu practice and philosophy (Arnold, 1961; Schimmel, 1975; Smith, 1943).

Over the course of more than eight hundred years of Moslem presence and three hundred years of Mogul rule in India, the small number of original Moslem invaders and immigrants was expanded by conversion of a considerable proportion of the indigenous population (Arnold, 1921; Lewis, Menage, Pellat & Schacht, 1971;Spear, 1965). As Lewis et al. (1971) point out, It was in the sphere of social life and customs that the influence of Hinduism on the Indian Moslems was most far-reaching. Since most of the people were converts from Hinduism, it was not possible for them to break away completely from their social background. In ceremonies connected with birth, marriage, mourning, etc. the impact of Hindu traditions was quite remarkable. (p. 436)

Arnold (1961, p. 289) has noted that, "Of many, nominally Muslims, it may be said that they are half Hindus: they observe caste rules, they join in Hindu festivals and practice idolatrous ceremonies." Thus, both the Moslem rulers and the originally Hindu converts to Islam remained aware of the Hindu tradition of reincarnation and retributive karma.

Lawrence (1979) suggests that Hindu-Moslem relations grew more strained after the predominance of Moslem rule ended with the British Raj because the British tried to heighten dissension between the Moslem and Hindu populace. He cites concern over the loss of power as solidifying the Sunni anti mystical tradition. Smith (1943) points out the impact of communalism in making Moslems and Hindus emphasize their differences, even before partition.

At the end of the British Raj, approximately one quarter of the population was Moslem. After independence was achieved in 1947 and India was divided into an Eastern and Western Pakistani (Moslem) state and a predominantly Hindu India, many Hindus from the new Pakistani states moved into India, and many Moslems in India moved to Pakistan, amidst widespread violence and rioting between the two groups. Nonetheless, many Moslems remained in India after partition and continue to be a strong presence,especially in northern India. In 1981, 11% of the population of India, or 75.4 million,were Moslem, of which most were Sunni (Europa Year Book,1988). Moslems account for 20- 50% of the population in the villages and towns figuring in the cases described below.

Moslems and Hindus do not now intermarry, as a rule, and may in some instances live in separate sections of cities. In smaller villages they tend to be interspersed, and in both village and city they have considerable commerce and association with each other. It is in this context that the Moslem and half-Moslem cases of the reincarnation type are found.

Methods of Investigating the Cases

The main methods used in investigating the Moslem and half-Moslem cases were the same as employed in the study of other cases. These methods include: interviewing the child and his or her family members; independently checking the accuracy of the statements the child made by interview- ing relevant witnesses and relatives of the person the child claims to be; searching for documents (autopsies, birth, and death certificates); repeated interviews when necessary.The methods of investigating cases of the reincarnation type have been thoroughly described elsewhere (Stevenson, 1974, 1975b, 1987).

Common Features of Cases of the Reincarnation Type

Stevenson (1986, 1987) has found that there is considerable cultural variation in features of cases of the reincarnation type. However, instances in which children spontaneously recall an apparent past life typically have a number of features in common, regardless of the culture in which they occur. The common features are: the early age at which the child begins to speak about the apparent previous life (between the ages of two and five years), forgetting the previous-life memories by the time the child becomes seven or eight years old, and a high incidence of violent death among the previous personalities. Children often recall the mode of death, particularly in cases in which the previous personality died violently, and sometimes have a related phobia. Typically, the previous personality in Indian cases died within the two years prior to the child's birth (Stevenson, 1986).

The Characteristics of Moslem and Half-Moslem Cases

The Sample of Cases

The 34 Moslem or half-Moslem cases among the 356 cases from India in the files of the Division of Personality Studies of the University of Virginia comprise nine percent of the Indian sample. I have not included in the analysis the brief synopses of eight Moslem or half-Moslem cases because the information is incomplete and has not been verified by Stevenson or his associates. The 26 cases I have included were at least cursorily investigated by Stevenson or his associate. With the exception of one case reported by K. K. N. Sahay in the 1920s the cases were all investigated between 1960 and 1989, that is, after partition.

Even for the cases I have included, information is missing in some in- stances, due to incomplete questioning, absence of documents, or gaps in the memories of the informants. Therefore the sample size is less than 26 for some of the features discussed below.

Location of the Cases

Like most of the cases on file at the University of Virginia, the 26 Moslem and half-Moslem cases are all from northern India. Fourteen of the subjects lived in Uttar Pradesh, seven in Rajasthan, three in Madhya Pradesh, and one each in Gujarat and in India's most northern state, Jammu and Kash- mir. Most of these cases were identified in the course of studying the other cases of the reincarnation type in India.

Religion of the Subject and Previous Personality

Of the 26 Moslem and half-Moslem cases, in 7 (27%) a Moslem child remembered being a Hindu in a previous life, in another 11 (42%) a Hindu child recalled being a Moslem in a previous life, and in 8 (31%) a Moslem child was identified as the reincarnation of a Moslem.

The majority of the Moslem subjects or previous personalities considered themselves Sunni Moslems. One subject from Rajasthan said he was Sunni but really more Sufi than either Sunni or Shi'ite. Three of the Rajasthan cases came from a special Merhat group described as a Moslem merchant caste. In one case, described further below, a Sunni Moslem girl claimed to have been a Moslem Bohora in a previous life. Although some Bohoras in India are Hindu (Gibb & Kramers, 1953), the Moslem Bohoras are members of the Isma'ili Shi'ite branch of Islam.

Sex of the Subject

Of the 26 cases, 5 (19%)of the subjects were female. There were no cases of cross-sex reincarnation in the sample. The incidence of cross-sex reincarnation among an Indian sample of 261 was 3%;and the incidence of female subjects was also slightly higher (36%) for the 271 Indian cases analyzed (Stevenson, 1986).

Proportion of Solved to Unsolved Cases

Among 3 of 7 (43%)of the Hindu-to-Moslem cases, 5 of 11 (45%)of the Moslem-to-Hindu cases, and 1 of 8 (13%)of the Moslem-to-Moslem cases, the case remained "unsolved" (that is, no one was found who met the description of the person the child claims to remember being). Cases in which someone corresponding to the child's statement has been identified are called "solved." This distribution of solved and unsolved cases is presented in Table 1.

The proportions of 4 out of 7 (57%)solved Hindu-to-Moslem cases and 6 out of 11 Moslem-to-Hindu cases (55%)are lower than the 77% of solved cases found among the much larger Indian sample analyzed by Cook et al. (1983). On the other hand, the 88%solved among the 8 Moslem-to-Moslem cases exceeds the proportion of solved cases in the larger Indian ~arnple.~ Contact and distance are relevant to whether a case is solved.

Contact Between the Families of the Subject and the Previous Personality

Of 16 solved Moslem and half-Moslem cases, in 5 (31%) the two families were unknown to each other, in 9 (56%) they had some knowledge of each other or were acquainted, and in 2 Moslem-to-Moslem cases (13%) they were related. Information on contact is missing for one solved Moslem to Hindu case.

In two other Moslem-to-Moslem cases the two families were unknown to each other, and in three cases they were acquainted. Among five Moslem-to- Hindu cases, there was slight knowledge of the existence of the previous personality's family in three, whereas in two cases the families were more closely acquainted. Of the Hindu-to-Moslem cases, in one case the subject's family had some knowledge of the existence of the previous personality's family, whereas in three cases they were unknown to each other. In two cases (one solved and one unsolved) the contact between the two families was very slight but involved theft of something by a parent of the subject from the previous personality.

In a larger sample of 183 cases in India analyzed by Stevenson (1986), 43% were unknown to each other, 41% acquainted, and 16% related. This sample contained 14 (or 8%) Moslem or half-Moslem cases, all of which are included in my sample.

Distance between the Domiciles of the Families Concerned

The distance between the subject's and the previous personality's places of domicile varied from within the same town or village (in seven cases), to a different village within 30 km (in five cases), to a considerable distance, ranging from 60- 380 km (in four cases).

Socioeconomic Statuses of the Families Concerned

Little information is available on the comparative economic/caste status for the Moslem and half-Moslem cases. However, of three Hindu-to-Moslem cases for which we have relevant information, in two cases the Hindu previous personality was wealthy whereas the Moslem subject was quite poor, and in one case the previous personality was poor and the subject more affluent. In one (unsolved) Moslem-to-Hindu case the Moslem previous personality was wealthier than the subject, although the subject's family was comfortably situated.

Stevenson reports (1987, p. 215) that in one-third of the cases in India the subject and previous personality have the same socioeconomic circumstances. Two-thirds of the remaining portion or 44% of the Indian cases recall a life in better circumstances or caste.

Age of First Speaking of a Previous Life

In the Moslem and half-Moslem sample, the mean age of first speaking of a past life was three years, with a range from one year to six years old. This range is similar to that found in a larger body of Indian (nearly all Hindu) cases in which the mean age of speaking of an apparent past life was 38.02 months (Cook et al., 1983).

Age at Death of the Previous Personality

The age of the previous personality at death ranged from 5-72.5 years old, with a median age of 50. The median age of the previous personality at death in a largely Hindu sample of 159 cases in India was 32 years (Stevenson, 1986).

Interval Between the Death of the Previous Personality and the Birth of the Subject

The interval in the Moslem and half-Moslem cases ranged from 8 hours to 36 months. The median interval was 9 months. This is similar to the median interval of 12 months in a sample of 170 cases (nearly all Hindu) in India (Stevenson, 1986).

Mode of Death of the Previous Personality

According to the Demographic Yearbook (1970) the incidence of violent death in the general population in India was 7.2% in 1970. The percentage of violent death in Moslem and Hindu cases in India greatly exceeds this. Of 12 solved Moslem and half-Moslem cases, the mode of death was violent in 10 (83%).The percentage of violent death was only slightly lower (82%)for the unsolved cases. Cook et al. (1983, p. 128) found that 49%of 193 solved cases in India had a violent mode of death, whereas 85% of 47 unsolved cases in their sample from India involved a violent mode of death. Cook et al.'s Indian sample included 6 solved Moslem or half-Moslem cases with information on mode of death. When these cases are eliminated from the sample, one finds that 49% of 187 solved Hindu cases had a violent mode of death, whereas 84% of 43 unsolved cases had a violent mode of death. The solved Moslem and half-Moslem cases have a higher incidence of violent mode of death than the solved Hindu Indian sample. The difference is statistically significant.The unsolved Moslem and half-Moslem cases and the combined solved and unsolved Moslem and half-Moslem samples are not significantly different from the Hindu Indian sample.

The violent causes of death in solved cases included six instances of murder, one case of suicide, and three deaths from accidents, of which one was snakebite, another being hit by a tractor, and a third from a flood. Of the unsolved cases, three involved murders and five involved accidents: in two cases the subject recalled dying in a flood, in two others falling (from a roof in one case and from a scaffold in another), and the fifth involved a fatal car accident. Interpersonal violence was more frequently present in solved cases than unsolved ones 4

Birthmarks

Stevenson ( 1974,1975b, l977,1980,1983b, 1985, 1987) has noted numerous cases in which a child who apparently recalled a previous life bore birthmarks or birth defects that corresponded to injuries or lesions on the body of the previous personality, many of which had been the cause of the previous personality's death. Stevenson (in press) has in preparation several volumes describing birthmarks and birth defects in cases of the reincarnation type. This includes detailed reports of the birthmarks of two Moslem boys in India included in the sample for this paper, those of Nasruddin Shah and Umar Khan. In the former case the child had a birthmark corresponding to a spear wound described in the postmortem report. In the latter (unsolved) case the child had birthmarks resembling bullet entry and exit wounds.

Twelve of the 26 subjects had birthmarks or birth defects of which 9 were said to be related to the previous life. Of the three cases in which the relation is unclear, in one unsolved case there is no knowledge of whether the birth- mark was related to the fatal fall the subject recalled, in one solved case the birthmark was not studied, and in the third the relation of the subject's birthmark to the previous personality's drowning is unclear. In three of the nine unsolved cases the subject had a birthmark, two of which were related to the child's (unverified) description of the mode of death of the previous personality.

Nine of the children in 17 solved Moslem and half-Moslem cases had birthmarks or birth defects, of which four related to fatal wounds sustained by the previous personality. This category includes the case of Naresh Kumar, whose case is described in Part II of this paper. In the other two cases the child was born with deformities said to relate to the cause of death of the previous personality. Neera Kathat was born without a left forearm and recalled being beset by people wielding staffs and swords. The postmortem report of the previous personality describes blows to all his limbs. The fourth subject, Giriraj Soni, was born with a twisted spine and a knoblike protrusion on the back of his head. He identified himself as a man who was cut down by a party wielding swords. The postmortem report of this case has not yet been located.

In two solved cases the unborn child's past-life identity was foretold in a dream of the mother, and the subsequently born child bore a birthmark or other physical feature related to the previous personality (but not to his mode of death). In one of these cases, that of Ali Kathat, he and the apparently unrelated previous personality were albino. The second case, that of Jalaluddin Shah, was among two cases (one solved and one unsolved) in which the child was born congenitally circumcised.

The Prophet Mohammed is said to have been "born circumcised and happy" (Ibn Saad, 1917, p. 64). In the Shi'ite tradition the 12 Imams were also said to have been congenitally circumcised (Sachedina, 1981). The Prophet Mohammed's congenital circumcision is cited as the source of the importance attached to circumcision ceremonies among both Sunni and Shi'ite Moslems (Gibb & Kramers, 1953),although circumcision was practiced by pre-Islamic Semites (Houtsma, Wensinck, Arnold, Heffening, & Levi-Provenqal, 1987, p. 957). Circumcision is not a practice followed by the Hindu population, so that being born congenitally circumcised is considered a Moslem trait. In one of the cases involving congenital circumcision, the child, Jalaluddin Shah, was Moslem, as was the previous personality. In the second (unsolved) case, the Hindu subject, Mukul Bhauser, remembered a life as a Moslem.5

Behavior of the Subjects Related to the Previous Personality

Phobias. Five of the 26 subjects (19%) had a phobia related to the mode of death. This is less than the 27% reported for the entire sample from India (Cook et al., 1983). In three cases in which the mode of death involved drowning (two in floods and one suicide in a well) the subject had a phobia of drowning. In one case, the phobia was manifested as a fear of expanses of water such as ponds or rivers, in another of thunderstorms (which produced the fatal flash flood), and in the third, of wells. Two other phobias related to death by murder. In one such case the child had a phobia of dulse fields, which was said to be related to the location of an apparently remembered murder. This subject also had a phobia of the previous personality's brother, reportedly one of the murderers. In another case involving murder, the sub- ject had a phobia of going out at night, which related to his apparent memories of being beset by murderers under cover of darkness. In another case, the child who recalled jumping in a well had an aversion if not a phobia of the previous personality's wife, with whom the child said he had quarreled just before committing suicide. Some aspects of philias and aversions related to the previous personality are discussed next.

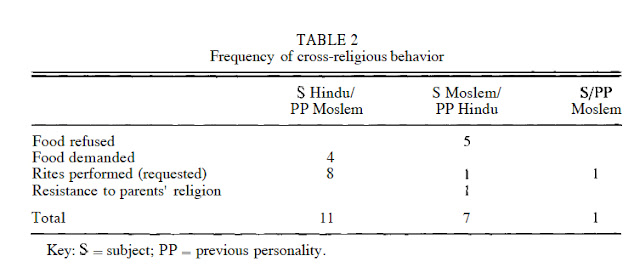

Cross-Religious Behavior of the Subjects. In the majority of half-Moslem cases the child exhibited traits characteristic of the religious group of the previous personality. Table 2 summarizes the nature of these cross-religious traits. Moslem children said to recall a Hindu life refused foods eaten by Moslems; Hindu children said to recall a Moslem life frequently requested Moslem dishes and performed Moslem rites.

Among the Hindu to Moslem cases, four out of seven children refused to conform to the diet of the parents. Umar Khan refused to eat meat, saying he was Hindu. Mohammed Hanif Khan initially refused to eat fish (the previous personality did not eat fish). Noor Bano refused to eat meat; in fact, Noor's mother indulged her in her vegetarian desires, although her father had been unaware that his wife cooked food for her separately. Nasruddin Shah refused to eat beef or fish, although he would eat mutton.

Conversely, in four cases in which a Hindu subject apparently recalled a previous life as a Moslem, the child asked his vegetarian parents to serve him meat. Giriraj Soni asked for mutton and eggs although his parents were vegetarian. Naresh Kumar asked for semia (a noodle dish favored by Moslems in northern India), eggs, and tea; his family drank tea, but did not eat eggs or serve semia. Subhash Singhal asked for Moslem food on a Moslem holiday. Kailash Narain Mishra wanted meat and special dishes for Moslem festivals, about which he used to talk.

Moslem habits of religious practice were noted among the Moslem to Hindu subjects more often than Hindu worship among the Hindu-to-Moslem subjects. In 2 of 7 (29%) Hindu-to-Moslem cases, the child resisted Moslem religion, or desired Hindu ceremonies. Nasruddin Shah resisted the Moslem religion and would not say Moslem prayers or go to the mosque. Mohammed Hanif Khan wanted a Rakhi thread tied on him when he observed the practice of this Hindu ceremony which celebrates the brother-sister bond.

However, in 8 out of 1 1 (73%) Moslem to Hindu cases the child exhibited Moslem traits, such as practicing namaz (the Moslem form of prayer said facing towards Mecca, in which one kneels and bows the head to the ground repeatedly, while reciting Arabic prayers). For example, Mukul Bhauser was observed bowing to perform namaz even before he could speak. Kailash Narain Mishra also performed namaz. Archana Shastri when two and a half years old was observed to say namaz for her father's health when he was ill. Thereafter, and for some time, she practiced namaz at 5:00 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. Hirdesh K. Saxena said namaz until he was five years old, and he wanted to go to Moslem services. Giriraj Soni began to practice namaz before his parents suspected he might be having memories of a previous life. He was continuing to do so up to the age of seven and a half (his age when I last met him); he was also attending the services at the local mosque each Friday. Naresh Kumar quietly practiced namaz from an early age, even before he first visited the previous personality's home. After going there, he insisted on wearing the Moslem cap which had belonged to the previous personality, despite considerable teasing from his Hindu playmates. Subhash Singhal practiced namaz when about three years old, and felt very attracted to ladies wearing the black outer covering worn by Moslem women in public in India. When we last interviewed this subject, he was thirty-five years old. He was continuing to go to a Moslem shrine to pray whenever he was trobled or wanted special divine assistance. He had introduced his wife to this shrine, but had never mentioned to his father that he was following this non-Hindu custom, suspecting parental disapproval. Manoj Nigam did not perform namaz but recalled that when falling to his (the previous personality's) death he had called "Allah."

In most of these cases in which the subject performed namaz, the parents noted the characteristic genuflection and that the child was quietly making a vocal prayer. Since the prayer was usually not audible, however, this makes it difficult to assess whether the child was repeating a prayer in Arabic, thus perhaps showing evidence of xenoglossy, or paranormal knowledge of a language not acquired since birth (cf. Stevenson, 1984).

Attitudes of the Adults Concerned in the Cases

Resistance to the Investigation and Solving of Cases. In four cases the Moslem relatives showed considerable hostility to the investigation of the case because reincarnation is against their doctrine. In three of these cases the child came from a Moslem family and recalled a life as a Hindu. In one Hindu to Moslem case studied by Stevenson, the Moslem community expressed opposition to the inquiries: the investigation took place under the protection of and in the quarters of the local Hindu patron of the area. In yet another case, described in Part I1 of this paper, the great-uncle of the subject belligerently said that reincarnation was not part of Moslem belief and there- fore we had no business investigating it. We were able to pursue questioning only because his view was not shared by his nephew or his nephew's wife and sons.

Opposition from the Moslems involved blocked further investigation in only two of the twenty-six cases in this study. In one Hindu to Moslem case which Stevenson hoped to study, he was told by a Moslem man that he should not look for such information about reincarnation among the Moslem community but only among the Hindus. This was despite the fact that this man's own sister had suggested Stevenson contact this man's wife, who had told her about the case.

In one Moslem to Hindu case (in which the boy recalled throwing himself in the well) studied by myself and previously by Pasricha, the Moslem rela- tives of the previous personality refused to have anything further to do with an investigation and told us with considerable hostility that they knew nothing about the case, even though several people had witnessed their initial meeting with the child and acceptance of him as their family member re- turned. Hindus in the area explained the reversal of the attitude of the previous personality's relatives as the result of the recent pronouncement of the Moslem leader that the Moslem parties concerned should have nothing to do with such an issue because it was contrary to Moslem doctrine.

However, Moslems do not resist acknowledging cases in all instances. K. K. N. Sahay persuaded the Moslem relatives of the subject and previous personality in a Moslem to Moslem case to sign or affix their mark to an affidavit endorsing the case (Sahay, 1927). The case is described in Part 11.In three other instances the case was accepted by the Moslem relatives as a valid instance of reincarnation. In one of these the Moslem daughter of the previous personality would come to visit the Hindu subject whenever the child became ill.

However, acceptance of a case does not necessarily imply a change in religious conviction. In one unsolved case, the Moslem mother of the subject suspected that her son's birthmark related to a past life, but when asked if she believed in reincarnation, said,"No." The father of another Moslem subject said, "The teachings of our Koran say that we should not believe in it." His brother said, " According to my religious conviction, no. But it may be possible."

Although only one of the Hindus, whether related to the child or the previous personality in half-Moslem cases, were reluctant to give information, I found that Hindus were apprehensive about and even feared Moslem opposition to the topic of reincarnation while they were trying to solve two (unsolved)Moslem to Hindu cases. One Hindu we questioned showed great reluctance to become involved in giving information about a Moslem reputed to have lived in his neighborhood who was said to have been reborn as a Hindu. A sense of uneasiness between the two religious communities seemed to result in more resistance and reluctance to solve the case than when the cases were within the same religious community. Thus one Hindu boy, Manoj Nigam, who recalled a life as a Moslem mason, was not allowed to go to the previous personality's house, even though it was in the same town and the child and parents passed by it. The child was observed greeting a woman as his wife, but his family had not even sought to learn the name of this woman.

Another Hindu boy, Mukul Bhauser, whose congenital circumcision was mentioned above, was merely ignored when he spoke of a previous life, but when he and his parents happened to pass through a town which he identified as the site of his (the previous personality's) death by drowning, his parents hid his face as they passed through the town. They had made no effort to trace the existence of the person their son claimed to have been, although they did not doubt the veracity of what he said, and they provided us with information about another half-Moslem case. In another case, when the Hindu father of a boy asked in the Moslem community if anyone corre- sponding to his son's statements had existed, he was told that someone did, but he did not seek out the previous personality's relatives. Part II describes a case in which the Moslem parents of a child had made no effort to solve the case.

Suppression of the Child's Speech and Behavior. Information about suppression is absent for many of the Moslem and half-Moslem cases. Of the 15 cases for which we have the relevant information, some form of suppression was practiced on all the cases in which children claimed to remember a previous life in the other religious community, and in three out of four of the Moslem-to-Moslem cases.

The measures used to suppress the child were no more severe for the Hindu to Moslem cases for which we have the relevant information than among the Moslem-to-Hindu cases, in which the cases posed no threat to religious doctrine. One Moslem family tried a combination of rotating the child counterclockwise on a millstone (to "undo" his past-life memories), tapping him on the head, and beating him. In the only other Hindu-to-Moslem case for which we have any information about suppression, the parents deny the allegation made by a fellow Moslem that they beat their daughter for remembering a past life as a Hindu, but they said they forbade her to speak about her previous life and feared that she was possessed by a demon. However, the mother went so far as to cook vegetarian food for her daughter because she refused to eat meat, saying she was a member of a Hindu vegetarian caste.

Hindu parents of a child who claimed to be a Moslem generally tried to take measures which they hoped would erase the child's previous-life memories. The techniques used included simply ignoring the child's claims, teasing, piercing the child's ear, turning the child on a potter's wheel, and taking the child to an exorcist out of fear that the child would go mad.

The fear that their child's attachment to a previous life would cause him or her to run away to the family of the previous life occurred in both some Moslem and some Hindu cases. The grandfather of one Moslem girl (who apparently recalled a previous life as a Moslem) recited a prayer or spell to make her forget, lest she run away to the previous personality's relatives. One Hindu girl who recalled a past life as a Moslem indeed tried to run away to her Moslem family, and a Moslem child was suppressed because the parents feared the child might run away to the village of the Hindu previous personality 6

Summary and Discussion

Although small, the proportion of Moslem and half-Moslem cases in the collection of the University of Virginia is approximately equal to the proportion of Moslems in the general population in contemporary India. In most respects the 26 Moslem and half-Moslem cases are very similar to the more prevalent Hindu-to-Hindu cases. However, the cases differ in several regards. First, the cases include numerous instances of a young child showing behavior appropriate for a religious community other than that of the parents. Secondly, the incidence of a violent mode of death was higher in the solved Moslem and half-Moslem sample than in the Hindu cases from India.

The similarity of the Moslem and half-Moslem cases to Hindu cases is unlikely to be the result of Moslem familiarity with specific Hindu cases. In only two cases did Moslem parents say that they had heard of a case of the reincarnation type among the Hindu population before the case developed in their far nil.... In all but one instance, the Moslem relatives had not believed that reincarnation took place before they were presented with a specific case. When confronted with the evidence of a case, even if the Moslem relatives had privately acknowledged a case, in some instances they publicly disavowed the case or any knowledge of it, because it was contrary to their religious doctrine.

Hindu parents who thought their child was remembering a life as a Moslem showed almost as much opposition to the development of the case as did Moslem relatives, even though the Hindu parents found no threat to their religion. In either situation the families of the child who claimed to re- member a past life in the other religious community were displeased sufficiently often so that they cannot be universally credited with fostering the child's identification with someone of a different religious persuasion.

I found no indication that the subject perceived the other religious community as dominant and, therefore, more desirable than the natal religion. The status-envy hypothesis would predict that more Moslem children would adopt Hindu behavior than vice versa, since Hindus greatly outnumber Moslems in India. However, more Hindu children adopted Moslem religious behavior than vice versa. In short, the status-envy hypothesis, which suggests that a child adopts an admired identity, does not seem to be applicable to these cases.

In the cases I have studied I have found no evidence that the subjects were treated as scapegoats by the parents, or abused in any way that might cause the child to adopt an alternate identity as appears to happen in some cases of multiple personality disorder (Bliss, 1986; Coons, Bowman, & Milstein, 1988). In the solved cases the statements and recognitions were accurate, on the whole, and the child's behavior appeared to be appropriate for the previous personality even when that person was a member of another religious community.

Endnotes

1

Children in cases of the reincarnation type often adopt behavior appropriate to the previous personality, which may contrast strikingly with the behavior of the child's family. The half-Moslem cases differ in that the behavior is appropriate to a different religious group with which the parents do not identify.

2

The eight cases not included in the analysis were reported in the Indian press. Three of these are reprinted by Sant Ram (1974), and one by Dklanne (1 924). All but 4 ofthe 26 cases included in the analysis were investigated by Stevenson, Pasricha, McClean-Rice, or myself. Of the other four, one was investigated by K. K. N. Sahay, one by K. S. Rawat, one by L. P. Mehrotra with the assistance of M. Khare, whereas one rests on the description given to Stevenson by Swami Krishnanand and a letter from the boy's father. I have included these four cases not investigated by Stevenson or his principal associatesfor the following reasons. K. K. N. Sahaywasa lawyer of Bareilly, U.P., who during the 1920s investigated and published (Sahay, 1927) seven cases, including that of his own son. Pasricha and Stevenson (Pasricha, 1990; Stevenson, 1987) fol- lowed up most of these cases and judged them to be authentic. K. S. Rawat worked with Stevenson on field trips in India, as did L. P. Mehrotra. Manjula Khare was at one time Steven- son's research assistant. Swami Krishnanand has also assisted Stevenson, who judged the report and letter from the subject's father acceptable for inclusion in an analysis.

3

Cook et al. ( 1983) have found that unsolved cases resemble solved cases in most features, except that the children in unsolved cases cease speaking about a previous life at an earlier age, make fewer verifiable statements, and have a higher incidence of violent death.

4

Cook et al. ( 1983) report that children who recalled a life that had ended violently were more likely to describe the mode of death than were children recalling a life that ended naturally. Stevenson and Chadha (1990) found that the interval between death and birth tended to be shorter in cases involving a violent demise and that the children refemng to a life that ended violently began talking about a previous life at an earlier age.

5

It should be noted that the congenital aplasia of the male prepuce (foreskin) has been noted in the medical literature in contexts where this anomaly had no special religious or cultural significance (Warkany, 197 1). James (1951) reports four cases in England and notes that the father (and in one case the father's father) had been born with the same aplasia of the prepuce, which suggested some evidence of hereditary transmission. Warkany (197 1)notes that in some cases congenital absence of the prepuce is accompanied by other, more severe malformations. This was not the case in the two instances cited above.

6

Suppression techniques are also used in cases completely within the Hindu community, because the parents feel hurt by having a child claim to belong to another family; annoyed by the child's demand to be taken to the other family; embarrassed that the child makes invidious comparisons between the circumstances of the previous family and the present family; con- cerned that a child who identifies him- or herself with a past life will be less well adjusted in the current life; and/or they believe that such a child may die prematurely. Pasricha (1990) reported that 23% of 30 fathers and 27% of 37 mothers used some method in an attempt to suppress the child's apparent recollection of a past life. Stevenson and Chadha (1990) report 41% of parents in an Indian sample of 99 cases used suppression techniques.

7

In a survey in one area of northern India (Uttar Pradesh), Barker and Pasricha ( 1979) found that cases of the reincarnation type were relatively rare: 2.2 people in 1000 appeared to have remembered a previous life.

References

Arnold, T . (1921). Saints and martyrs (Muhammadan in India). In J. Hastings (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics (pp. 68-73). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Arnold, T. (1961). The preaching of Islam: A history of the propagation of the Muslim faith. Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf.

Barker, D. S., & Pasricha, S. (1979). Reincarnation cases in Fatehabad: A systematic survey of north India. Journal ofAsian and African Studies, 14, 231-240.

Bliss, E. (1986). Mliltiple personality, allied disorders and hypnosis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brody, E. (1979). Review: Cases of the reincarnation type. Ten cases in Sri Lanka, by Ian Stevenson. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 73(l), 71-8 1.

Burton, R. & Whiting, J. W. M. (1961). The absent father and cross-sex identity. Merrill Palmer Quarterly of Behavior & Development, 7(2),85-95.

Cook, E. W., Pasricha, S., Samararatne, G., Maung, U Win, & Stevenson, I. (1983). A review and analysis of "unsolved" cases of the reincarnation type: 11. Comparison of features of solved and unsolved cases. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 77, 115- 135.

Coons, P., Bowman, E., & Milstein, V. (1988). Multiple personality disorder: A clinical investigation of 50 cases. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1 76(9), 5 19- 527.

Dklanne, G. (1924). Documents pour servir ci l'etude de la reincarnation. Paris: Editions de la B.P.S.

Demographic Yearbook. (1970). New York: United Nations.

Europa Year Book. (1988). London: Europa Publications Ltd.

Gibb, H. A., & Kramers, J. H. (1953). Shorter encyclopedia of Islam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Haimendorf, C. (1953). The after-life in Indian tribal belief. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 83, 37-49.

Hodgson, M. G. S. (1974). The venture of Islam. Vol. III. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hollister, J. (1953). The shi'a of India. London: Luzac and Company, Ltd.

Houtsma, M. T., Wensinck, A. J., Arnold, T. W., Heffening, W., & Levi-Provencal, E. (Eds.).

(1987).E. J. BrillSJirst encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Vol. IV. Leiden: E. J. Brill. Ibn Saad. (1917). Biographie Muhammed's. Band I. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

James, T . ( 1951). Aplasia of the male prepuce with evidence of hereditary transmission. Journal

of Anatomy, 85, 370-37.

Lawrence, B. (1979). Introduction. In B. Lawrence (Ed.), The rose and the rock: Mystical and rational elements in the intellectual history of south Asian Islam (pp. 3-13). Comparative studies on southern Asia, No. 15. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Program in Comparative Studies on Southern Asia, Islamic and Arabian Development Studies.

Lewis, B., Menage V. L., Pellat, C., & Schacht, J. (Eds.). (1971). The encyclopedia ofIslam. Vol. I  . (New Edition). London: Luzac & Company.

Mills, A. (1989). A replication study: Three cases of children in northern India who are said to remember a previous life. Journal of Scientijic Exploration, 3(2), 133- 84.

Obeyesekere, G. (1980). The rebirth eschatology and its transformations: A contribution to the sociology of early Buddhism.In W. O'Flaherty (Ed.),Karma and rebirth in classical Indian traditions (pp. 137- 164). Berkeley: University of California Press.

O'Flaherty, W. (1980). Karma and rebirth in the Vedas and Puranas. In W. O'naherty, (Ed.). Karma and rebirth in classical Indian traditions (pp. 3- 37). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pasricha, S. (1990). Claims of reincarnation: An empirical study of cases in India. New Delhi: Harman Publishing House.

Sachedina, A. A. (1981). Islamic messianism: The idea of madhi in twelver Shi'ism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Sahay, K. C. (1927). Reincarnation:Verijied cases of rebirth after death. Bareilly: N. L. Gupta. Sant Ram. (1974).The riddle of rebirth. Hoshiarpur, Punjab: Vishveshvaranand Institute Publication 626. [in Hindi]

Schimmel, A. (1975). Mystical dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Smith, W. C. (1943). Modern Islam in India: A social analysis. Lahore: Ripon Printing Press. Spear, P. (1965). A historyof India. Vol.2. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Stevenson, I. (1966). Cultural patterns in cases suggestive of reincarnation among the Tlingit Indians of southeastern Alaska. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 20, 229- 243.

Stevenson, I. (1969). The belief in reincarnation and related cases among the Eskimos of Alaska. Proceedings of the ParapsychologicalAssociation, 653-55.

Stevenson, 1. (1974). Twenty cases suggestive of reincarnation.Charlottesville:University Press of Virginia. (First published Proceedings of the American society for psychical research, 26: 1-362, 1966.)

Stevenson, I. (1975a). The belief and cases related to reincarnation among the Haida. Journal of

Anthropological Research, 31(4), 364- 375. (Reprinted with revisions, Journal of the American society for Psychical Research, 71, 1.77-189, 1977.)

Stevenson, I. (1975b).Cases of the reincarnationtype. Vol. I. Ten cases in India. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson,I. (1977).Cases of the reincarnation type. Vol. II. Ten cases in Sri Lanka. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1980). Cases of the reincarnation type. Vol. ZII. Twelve cases in Lebanon and Turkey. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1983a). American children who claim to remember previous lives. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 171(12),742-748.

Stevenson, I. (1983b). Cases of the reincarnation type. Vul. IV . Twelve cases in Thailand and Burma. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. ( 1984). Unlearned language: New studies in xenoglossy. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson,I.(1985).The belief in reincarnation among the Igbo of Nigeria.Journal of Asian and African Studies, 20( 12), 13- 30.

Stevenson, 1. (1986). Characteristics of cases of the reincarnation type among the Igbo of Nigeria. Journal o f Asian and African Studies, 21(34), 204- 216.

Stevenson, 1. (1987). Children who remember previous lives: A question of reincarnation. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson,I.(inpress).Birthmarks and birth defects: A contribution to their etiology.NewYork: Paragon House Publishers.

Stevenson, I., & Chadha, N. K. (1990). Can children be stopped from speaking about previous lives?Some analyses of features in cases of the reincarnation type. Journal of the Society.for Psychical Research, 56(818).82-90.

Warkany,J.(1971). Congenital malformations:Notes and comments. Chicago:Year Book Medical Publishers.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 189-202, 1990

Moslem Cases of the Reincarnation Type in Northern India:

A Test of the Hypothesis of Imposed Identification

Part II: Reports of Three Cases

Abstract- The author describes three cases of the reincarnation type in India in which either the subject or the previous personality (or both) were Moslem. In one case both the child and the person she was said to be were Moslem. In the second case, a Hindu child claimed to be a Moslem. The third case not only remains unsolved (that is, no one was ever found who corresponded to the child's statements), but probably represents a spurious case. In this case or non-case, a Moslem child gave some indication of recalling being a Hindu Brahmin. Moslems do not endorse the concept of reincarnation and, therefore, approach cases skeptically. The cases are presented in some detail so the readers can assess for themselves to what extent the cases represent evidence that something paranormal by Western standards (such as reincarnation) may be taking place.

Introduction

In a companion article (Mills, 1990) I compared the 26 cases of the reincarnation type in northern India (on file in the Division of Personality Studies at the University of Virginia) in which either the subject or the person whose life was apparently remembered (or both) were Moslem with the features of the more common cases among the Hindu population of India. (Cases in which both the subject and the previous personality were Moslem are called "Moslem cases." Cases in which either the subject or the previous personal- ity was Moslem but the other was Hindu are called "half-Moslem"). That article noted that these Moslem and half-Moslem cases are in general similar to the more common Hindu cases in India, and that Moslem or half-Moslem cases are of particular interest because it is unlikely that a child's identification of him- or herself as a person of another religious community would be covertly fostered by the parents. Since Moslems in India do not in general believe in reincarnation, encouragement of cases by the Moslem community is even more unlikely. The companion article described some of the opposition to the investigation of the cases that has been encountered.

This article presents descriptions of three Moslem or half-Moslem cases (although one may be a pseudo-case). The case of Doohi Khan is one of the eight Moslem-to-Moslem cases in the sample from India. The case of Naresh Kumar is one of the 1 1 half-Moslem cases in which a Hindu child identified himself as a Moslem. The case of Chinga Khan is probably a spurious case of a Moslem said to recall the life of a Hindu. There are seven cases of Moslem children who claimed to have been a Hindu in a previous life. I include it as an example of how rumors of a case (or non case) can come into existence. I have not included it in the sample of seven cases in which a Moslem child is said to recall the life of a Hindu analyzed in Part I because it probably belongs to the small group of cases involving deceit or self-deceit of which Stevenson and his associates have reported seven examples (Stevenson, Pasricha, & Samararatne, 1988). The presently reported cases are described in some detail so the reader can assess the kind of evidence they present.

Case Reports

The Case of Doohi Khan--------------------------

The case of Doohi Khan rests on the affidavit K. K. N. Sahay had signed by the relatives of the subject and the previous personality in this Moslem to Moslem case. On October 17, 1926, Mr. Sahay wrote up the following affidavit, quoted in Bose (1960, p. 94).

My daughter Pirbin died at the age of five. One year after her death the daughter of Mohammed Madari Khan of this village gave birth to a girl child. When the girl was five years old, I chanced one day to go on some business to the house in which she was living. She recognized me and called me"Father." I brought her to my house with me and she recognized my wife as her mother and my two sons are her brothers. She also knew my parents, grandparents, two brothers, and near relatives of this village; namely, Mordan Khan, Pir Khan, Alisher Khan, Sahib Khan, Tej Khan, etc. She even told which things of the house she had used as her own. She is now with her husband, Mohammed Khandan Khan in Sarolly Village of [District] Bareiily.

(Signed) Mohammed Jahan Khan Hafiz (Dated) October 17, 1926

Witnesses

Signature: Hakim Babu Ram (Landlord of Karanpur Vill.)

Thumb Impressions

1) Mohammed Mordan Khan (Village Head) 2) Mohammed Nur Khan (Village Head by government nomination) 3) Mohammed Rashid Khan 4) Mohammed Monser Khan 5) Mohammed Jaber Khan 6) Mohammed Mir Sahib 7) Mohammed Maduri Khan

S. C. Bose (1960, p. 94), who cited this case, commented, "I congratulated Mr. Sahay on getting this valuable statement and told him probably no one but a lawyer could have done so. He laughed and admitted he had obtained it only with the greatest of difficulty."

Further Attempts to Study the Case

In 1976, some 50 years later, and again in 1979, Ian Stevenson tried to meet the subject and her husband at Sarolly, and/or the original informants of the case, without success. T o what extent the failure was due to the great passage of time, to the considerable movement of Moslems into Pakistan after Partition in 1947, or to reluctance on the part of some Moslems to discuss a topic disavowed by their faith, it is difficult to say. The subject of the case would have been at least sixty and would have been unlikely to recall the statements she had made when five, if her case followed the pattern of the numerous cases which have been better studied (Cook, Pasricha, Samararatne, U Win Maung, & Stevenson, 1983; Pasricha, 1990; Stevenson, 1987).

The Case of Naresh Kumar--------------------------

In this half-Moslem case the Hindu child Naresh Kumar Raydas identified himself as the deceased son of an elderly Moslem Fakir. Naresh Kumar Raydas (henceforth called Naresh) was born in Baj Nagar about April 1981. No exact record of his birthdate is known to exist.' He was the third of four children of Guru Prasad Raydas and his late wife, who lived in the village of Baj Nagar (population c. 600). Baj Nagar is about five kilometers from the city of Kakori, in the District of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh.

The previous personality, Mushir Ali Shah (henceforth called Mushir) was the eldest son of the Fakir Haider Ali Shah by his second wife. Mushir had lived with his parents in the town of Kakori. Mushir was employed driving a horse-cart filled with fruit or vegetables from Kakori to the market at Luck- now. He was approximately twenty-five years old when, on June 30, 1980, a tractor struck him and his cart filled with mangos. Mushir died on the spot, which was on the road from Kakori to Lucknow where ir passes about a half kilometer from the village of Baj Nagar.

Investigation of the Case

I learned of the case in August 1988 and interviewed Naresh and his family then, again in December 1988, and in July 1990. Satwant Pasricha studied the case in November 1988. The informants at Baj Nagar were Naresh; Naresh's father, Guru Prasad; Guru Prasad's brother's wife, Rukana; Guru Prasad's nephew's son, Chandi Ram; and Istaq Ali, the Moslem next-door neighbor of Naresh and his family. Naresh's mother had died some months before we began investigating the case. In addition, Pasricha interviewed Naresh's paternal grandmother. In Kakori I interviewed the Fakir and his wife; their married daughter, Waheeda; the previous personality's brother, Naseer; the wife of Shafique, who was a neighbor of Mushir's; Zaheed Ali and his wife; and an employer of Mushir's, one Sukuru. In the village of Katoli I interviewed Nokay La1 Raidas, who was with Mushir at the time of his death.

Prior Contact Between the Two Families

During his lifetime Mushir was not known to Naresh's family. However, his father, the Fakir Haider Ali Shah, was known to them as a Moslem householder who had dedicated his life to God. The Fakir came every Thurs- day to Naresh's village and home on his round of asking for alms and offer- ing prayers. Naresh's parents called him Kubra Baba. Naresh's family had not heard of the Fakir's son Mushir until his death. When word of the accident that had killed Mushir spread to Baj Nagar, many villagers, including Naresh's parents and great aunt, Rukana, came to see the body. They learned then that the victim was the son of the elderly Fakir Kubra Baba.

Development of the Case

Early Behavior of Naresh Later Related to Mushir. When Naresh was quite young, he did and said things that were puzzling to his parents and that they only later considered early indications of his identification of himself as Mushir. At the time they paid little attention to these traits.

When Naresh first started speaking, at the age of about two years, he often said, "Kakori, Kakori" and also"karka, karka," which means "horse-cart" in the local dialect. His parents did not know why he said these words. When

Naresh was first able to walk, he would follow after the Fakir Haider Ali Shah when he came to Baj Nagar on his rounds, begging for alms and praying for people. Naresh would go with the Fakir to the next two or three houses and then return to his own home. Naresh called the Fakir Abba, the Urdu word for father, used by Moslems and some Hindus in this area of Uttar Pradesh. Naresh's parents told him he should call the Fakir by the Hindu term, Baba.

From the time Naresh was about two years old, he was sometimes observed kneeling down at home as if to perform namaz, the Moslem form of ritual prayer. If Naresh noticed that he was being observed, he would stop.

Naresh's Explicit Identifiation of Himself as Mushir. By August 1987, when Naresh was about six years old, he had said he was a Moslem and from Kakori so often that his mother approached the Fakir when he was in Baj Nagar and asked him what she should do about this. The Fakir, although not himself an adherent of the concept of reincarnation, advised her to take the child to Kakori and see which house he was from. Naresh's mother said, "How can I take him to a house I don't know?"

Later that day Naresh saw the Fakir and again called him Abba, and this time he also said, " Don't you recognize me? In my house there are five neem trees. I was hit by a tractor." Naresh then said that the mangos were scattered around and that Naresh's mother had eaten two mangos. He expressed con- siderable hostility at this, and asked the Fakir to take him home with him, which the Fakir declined doing. The next morning Naresh persuaded his mother to take him to the Fakir's house in Kakori. Naresh's mother told the Fakir that on the way she had asked someone for directions to the Fakir's house.Naresh responded with annoyance, saying, "You mean I don't know? Come, I will show you." Naresh's mother told the Fakir that Naresh then led her to the Fakir's house, which is in an area of Kakori where he and his mother had never been before.

When they arrived, Naresh again called the Fakir "my Abba [Father]." Naresh called the Fakir's wife Amma (Mother), and recognized Mushir's brothers and a sister present, as well as her husband, whom he called by name, Mohammed Islam.

Naresh then pointed out one of five metal suitcases inside the house, said it was his, and asked for the key. Naresh described the contents before opening it, saying (according to the Fakir) that there were three rupees and his cap in the trunk, When he opened it, these items were inside. The Fakir and his wife said that they had not known there were three rupees inside Mushir's trunk.

Naresh then asked the Fakir's wife, Najima, "Where is my younger brother, Nasim?" She said he was sleeping. Naresh went to him and hugged him and started kissing him. Najima then asked Naresh how many brothers and sisters he had. Naresh said that he had five brothers and six sisters and that one of the sisters was a stepsister. This was correct for the time Mushir was alive. Najima, pointing to Sabiah, a girl about six years old, then asked him who she was. Naresh said, "She was in your stomach at that time." This youngest child of the Fakir's was born three months after the death of Mushir.

The Fakir's wife then examined Naresh and noted that he had a mark on his head which corresponded to a mark on Mushir where she had struck him with tongs when exasperated that he did not eat. (When asked in 1990, Najima said she had heard that birthmarks may relate to an earlier life). I found this mark difficult to see in 1988 because it is in Naresh's thick hair. Najima thought the mark had faded in the year since she first met Naresh, but pointed out an area on the back of Naresh's head in which the scalp appeared to have a darker pigmentation than the surrounding area.

The Fakir and his wife also noted that Naresh had a slight depression near the middle of his chest. (When I examined him in 1988, I could see this depression, which was at the lower end of the sternum, extending across the midline, but more to its right than its left.) In 1988, but not in 1990, the Fakir and his wife said that this depression was at the same place as a wound in Mushir's chest that occurred during his fatal accident. By 1990, the depres- sion in Naresh's chest was less evident.

Naresh recognized a number of people from Kakori who had gathered at the Fakir's house on Naresh's first visit. One of these was the wife of a man called Zaheed, and he is said to have asked her, "Have you not given my 300 rupees to my Abba?" In fact, three days after Mushir's death Zaheed had given the Fakir the 300 rupees that Mushir had deposited with him. Naresh was asked if he recognized a particular old lady who arrived at the Fakir's house. This lady told me that he had not. However, Mushir's mother said that Naresh, out of this lady's hearing, had said that she was " Shafique's wife who lives near the mosque." This was correct.

When Naresh was going to be sent back home from the Fakir's house with five rupees, he said, "What do you mean? That you will send me off without giving me tea and egg?" Mushir had been very fond of tea, eggs, and semia. Tea and eggs were foods that he had every day.

Naresh's Continued Identijication of Himself as Mushir. After Naresh re- turned from Kakori, he wore Mushir's Moslem-style cap every day for months, despite the teasing he received from other children about being a Moslem man. According to Naresh's father, after going to Kakori Naresh's identification of himself as a Moslem, and as Mushir, became stronger than before, and he performed namaz (the Moslem form of prayer) more often and wanted to be given tea, egg, and semia. However, his father said that during the year that had elapsed since Naresh first went to the Fakir's home in Kakori, the intense identification had begun to fade so that Naresh had begun to talk more from the point of view of Naresh and less from the point of view of Mushir.

Suppression Efforts

Some time after Naresh's first trip to the Fakir's home, Naresh's parents, in an effort to make him forget his identification of himself as Mushir, had taken him to a Mazaar, a site where a Moslem saint was buried. The Fakir felt this was responsible for the fact that Naresh had begun to show less interest in him when the Fakir arrived in Baj Nagar to beg.

Attitudes of Moslems Regarding the Case

The Fakir said that he did not believe in reincarnation before this case. After Naresh approached him and said he was his son, the Fakir felt deeply troubled. Unable to sleep, at midnight he prayed,"Allah, what is this mystery?" Naresh's recognitions the following day convinced the Fakir that Naresh was his son Mushir reborn. At first the Fakir's wife was shocked that a young boy claimed to be her son. However, she too became convinced that Naresh was her son reborn. In recounting the events, the Fakir and his wife were moved to tears. The Fakir's voice shook with emotion every time he recounted the incidents.

Perhaps it is because the Fakir was and is respected as a Moslem holy man that I found no opposition to the study of the case on the part of any of the numerous Moslems whom I interviewed regarding the case. Most people would give evidence about the case and then repeat that they did not believe in reincarnation. For example, Waheeda, the sister of Mushir, described how Naresh had identified her by saying, "You are my sister." When I asked her how she had responded, she said, "We don't believe in reincarnation."

The Fakir is now himself so familiar with the reincarnation explanation of the case that he said to me and the assembled gathering in July 1988, as an aside, " This is my last life on earth," to which a prominent Moslem resident of Kakori responded, "How can you know? Only God can know."

In short, despite the fact that the doctrine of reincarnation is not a part of the Sunni Moslem tradition, the case involving the Fakir's son has not only caused most members of the Fakir's family to entertain the concept, but softened the attitude towards reincarnation in the surrounding Moslem community as well. This lack of opposition was not typical of the other Moslem and half-Moslem cases, as Part I attests.

Comment on the Paranormal Features of the Case

Some of the features of this case are difficult to explain by normal processes of communication and standard psychological premises. These features include Naresh's identification of himself as someone he did not know and his knowledge about the life of this person. This knowledge was ex- pressed in some of his statements about Mushir's home and possessions, his recognition of Mushir's family and people known to him, and his knowledge of money owed to Mushir. His birthmark and the slight birth defect apparent in 1988 may also have a paranormal origin.

As noted above, Naresh's identification of himself as Mushir appears to have begun before he was able to verbally make this clear to his family or the Fakir. His persistent mentioning of Kakori and a horse-cart and his attraction to the Fakir and early practice of namaz are evidence of this early identification.

Naresh's practice of namaz may have derived from observation of his next-door neighbor Istaq Ali or of other Moslems performing this ritual. According to a resident of Baj Nagar, 80% of the village was Moslem. Nonetheless it is not common for Hindu children to say that they are Moslem. Naresh's early performance of namaz is consistent with his identifying himself as Mushir.

Naresh's identification of himself as the son of the Fakir was not based on a wish to identify himself with better material conditions. Both the Fakir's family and Naresh's had some difficulty meeting their material needs. The Fakir had 14 children, of which the eldest were working and helping to add to the meager living the Fakir gained by begging for alms. Nonetheless, the family was materially quite poor. Naresh's father owned four acres of land which he worked, but Naresh's family was not much more affluent than the Fakir.

Many of Naresh's later statements (verified as correct) also indicate the depth of his identification of himself as Mushir. Some contained infomation that was publicly known, but some do not. For example, Naresh's description of the accident and of the spilling and eating of the mangos was correct, but these facts were known to Naresh's parents. Naresh may have heard this detail as well as a description of the fatal accident that occurred before his birth, but it is unlikely that such information would have much saliency for a boy from Baj Nagar. Knowledge of the events would not explain Naresh's first-person identification with them. Naresh's statement that there were five neem trees in the courtyard of the Fakir's home was made before Naresh had ever been there and suggests paranormal knowledge.

The recognitions Naresh made in Kakori, of people and objects, were also correct. Critical observers may note that clues may be inadvertently or un- consciously supplied in the charged setting of "past-life" reunions by the crowd of bystanders or by the people directly involved. Whereas such clues may account for some recognitions, they are unlikely to account for the spontaneity and appropriateness of the child's behavior towards these people. This is exemplified by Naresh's hugging and kissing Mushir's youngest brother Nasim the first time he saw him. Such action was entirely appropriate for Mushir and unlikely for a Hindu child who had never seen Nasim before. One of the people apparently recognized by Naresh was the wife of a man who owed Mushir money. It is unlikely that the bystanders would have supplied information about the amount of money Mushir was owed.

Naresh's recognition of Mushir's suitcase-cum-trunk, identification of it from a group of others, and knowledge of its contents seems to have been spontaneous and also indicates paranormal knowledge. For example, as noted above, Mushir's parents had not known there were three rupees in the trunk.

The slight defect on Naresh's chest, which is apparent in photographs taken in 1988, may also require some explanation. There is a rare birth defect known as funnel chest (pectus excavatum), the incidence of which has been found in different series to vary between 1-4 births per 10,000 (Degenhardt, 1964). Degenhardt (1964) and Nowak (1936) noted that the defect sometimes occurs in several members of a family as a dominantly inherited trait. However, a genetic factor seems improbable in Naresh's case because no other members of his family had a similar defect. The correspondence of the depression in Naresh's chest to the place where Mushir's ribs were broken in the fatal accident, according to Mushir's brother and the man who was with him at the time of the accident, suggests a causal relation to Mushir's wound. However, to date I have not obtained the autopsy, and the police report mentions only that Mushir died on the spot.

The [Questionable] Case of Chinga Khan------------------

The case of Chinga Khan is unsolved, that is, no one corresponding to the child's description was found to have existed. Indeed I do not consider it as a case at all, but I include a report of it because it is important to report the weakest cases as well as the strongest in the interests of evaluating how cases come to be defined as such and what evidence they present that some paranormal process is involved.

Investigation of the Case

Stevenson and Pasricha heard about the case in 1987 when they were in Bharatpur investigating another case, but they did not investigate it. I investigated the case on January 2 and January 9, 1989 with the assistance of Dr. N. K. Chadha, and Geetanjali Gulati. The information about Chinga rests on what Chinga's parents and elder brother said, what Chinga shyly added, and the testimony of one neighbor lady. In addition Hari Sharma (a man who had probably erroneously been identified by third parties as being the son of the previous personality), a street vendor, and Babbu, the son of a betel leaf seller, were interviewed.

Opposition to the Investigation

Chinga's great-uncle said with great hostility that they do not believe in reincarnation, and he sought to stop me and my translators from asking questions and taking notes about the case. His opposition was so belligerent and persistent that the study of the case would have been impossible if any other members of the family had sided with him. However, Chinga's mother had begun giving us information before the tirade became heated, and Chinga's elder brother and father, who were not present when this elderly man voiced such strident opposition to the study, were open to being interviewed.

Development of the case

Chinga Khan was born in Bharatpur, Rajasthan in about 1980. He was the son of Ajmeri Babu Khan and Jora Khan, who were Sunni Moslems and as such did not endorse the concept of reincarnation. Ajmeri Khan had cows which he sold and milked. Chinga had one elder brother, Chandu, who was about five years his senior. Chinga's mother had had 1 I children, of which Chinga and Chandu were the only ones alive.

Chinga was born with a left thumb that was bifurcated into two. To have six digits is considered a sign of good luck in India. Chinga's father considered him a lucky child and credited him with the ability to foretell events. He was called Chinga because it means " six-fingered."

When Chinga was young, according to his parents and brother, he made the following statements: He said that he was a Brahmin Pandit (apparently both words were used) and that he had two sons. Chinga's father said he had given the names of the sons, but he did not remember what they were. Hari Sharma said that when he went to learn about the case a year before our investigation, Chinga's brother had told him that Chinga had previously given the names of the sons. However, when we interviewed Chinga's brother, he did not think that Chinga had named them specifically.

Chinga's father (but not his mother and brother) said that Chinga had said he had a paan (or betel leaf) shop. (Vendors of paan are called paan walas.) His mother reported that he had said that his shop was in Laxman Mandir. There is a Laxman Mandir market area about two kilometers from Chinga's home. His parents independently said that Chinga had said there was a barber shop opposite and a sweet shop nearby. Chinga's father (but not his mother) said that Chinga used to go off towards the area of Laxman Mandir. Chinga had ceased making these statements some time before I began studying the case.

When Chinga was small, he had two habits which suggested that he was a Brahmin; namely he refused to eat meat and eggs, and he repeatedly washed his hands (and less often his feet and body). Whether these traits occurred before Chinga began making statements which his parents thought might be referring to a past life I did not ascertain. His father also noted that Chinga has a fair complexion unlike himself and his elder son, which he apparently thought could be explained by a reincarnation interpretation.

Continuation of Anomalous Behavior

Chinga was repeatedly washing his hands and keeping a vegetarian diet up to the time I investigated the case, when he was about eight years old. Chinga's mother said that his hand washing had been so frequent that she had taken him to a doctor to see if his hands itched or had some affliction which accounted for the repeated ablutions (one might wonder whether the anomaly of the divided thumb prompted this habit). The doctor said there was nothing wrong with his hands. He had no other obsessions.

Regarding Chinga's continued vegetarian diet, Chinga's mother indicated that she did not eat meat because of her poor teeth, although she prepared it for her husband and elder son. There were no Brahmins in the neighborhood whom Chinga could have been taking as a role model. However, the Moslems of the area were just as much aware as the Hindus that Brahmins are particularly concerned about cleanliness and are (typically) strict vegetarians.

Development of Rumors about the Case

Word that a Moslem child was saying he was a Pandit and had a paan shop had spread throughout the neighborhood and eventually reached a kachori wala (a man who cooks and sells a food called kachoris from a cart) in the Laxman Mandir market about a year before our investigation. The kachori wala was told by a customer (whom he had not seen before or since) that a Moslem boy in a particular neighborhood was saying that he was a Pandit and had a paan shop. The kachori wala said that this customer had told him the names the child had given of "his" sons, and they were the names of Hari Sharma and his brother. The kachori wala had known the paan shop and the sons who ran it and their late father, by name, for many years. His cart was across and up the street about a hundred yards from Hari Sharma's paan shop and positioned so that both Hari Sharma and the kachori wala could see what was taking place at each other's establishment.

The kachori wula then went to Hari Sharma and told him what he had heard, and together they set out to find the child. They arrived at Chinga's house and met his elder brother but found that Chinga had gone with his mother to her family in Mathura, a city a considerable distance away. The Brahmin Hari Sharma said he did not believe in reincarnation in any case, and he did not further pursue the matter until I arrived a year later and made inquiries.

Hari Sharma was skeptical about the case. His father had died in about 1963 after an illness of a few days when he was between sixty and sixty-five years old. He had never had a paan shop. Hari himself had opened the paan shop in about 1977. The location of the shop, in the Laxman Mandir market, fits the description attributed to Chinga, but could not have been garnered from his late father's memory. Further, the sweet shop Chinga is said to have referred to was not present during Hari Sharma's father's life.