Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 217-238, 1988

Abstract- Three new cases in Sri Lanka of children who claim to re- member previous lives were identified before the statements made by the children subjects of the cases had been verified. The authors made a written record of what the child said and then located a family correspondingto the child's statements. Although none of the children stated the name of the deceased person whose life the child seemed to remember, they all fur- nished details that, taken together, were sufficiently specific to identify one particular person as the only person corresponding to the child's statements. Careful inquiries about the possibilities for the normal communication of information from one family to the other before the case developed provide no evidence of such communication and make it seem almost impossible that it could have occurred. The written records of exactly what the child said about the previous life make it possible to exclude distortion of memories of the child's statements on the part of informants after the two families concerned have met. The children seem to have shown para- normal knowledge about deceased persons who were previously completely unknown to their families.

Introduction

Children who claim to remember previous lives can be found with little difficulty in South Asia, parts of western Asia, West Africa, and in some other parts of the world. A survey of a randomly sampled population in northern India showed an incidence of one such case in 500 persons (Barker & Pasricha, 1979). Previous articles and books have reported 62 cases of this type in detail (Stevenson, 1974, 1975, 1977, 1980, 1983). In addition, the features of the cases have been analyzed in cross-cultural comparisons (Cook, Pasricha, Samararatne, U Win Maung, & Stevenson, 1983) and in comparisons of cases occumng two generations apart (Pasricha & Steven- son. 1987).

The subjects of these cases often show behavior, such as phobias, philias, and play, that is unusual in their family but that accords with behavior that the person whose life the child recalls was known to have shown or that could be plausibly attributed to him. However, such behavior could derive from the child's belief that he had been a particular person. For example, a phobia of knives would be appropriate for a person who believed that he had been stabbed to death in a previous life; the belief by itself is not evidence that the subject had a previous life that ended in stabbing. More valuable evidence can, however, derive from the child's statements about the pre- vious life. Yet not all of these statements can qualify as satisfactory.For this to happen we must know not only that the statements are correct for events in the life of a particular person; we must also know that the child could not have obtained the information in his statements by normal means of communication. These are difficult criteria to satisfy, for reasons that we shall next explain.

First, in a large number of cases the child does not make statements that are sufficiently specific to permit tracing a deceased person corresponding to them. (We call such a person the "previous personality" of the case.) These unverified cases (which we call "unsolved cases") may include memories of real previous lives; but we cannot know this, and they may be only fantasies. The incidence of unsolved cases varies from one country to another; they are particularly common in Sri Lanka and among non-tribal cases of the United States. In a second large group of cases the subject's family and that of the previous personality were acquainted before the case developed, and information about the previous personality might have reached the subject normally. There remains a third large group of cases in which the two families were unrelated and unacquainted before the case developed. Moreover, they often live so far apart- perhaps 50, 100, or more kilometers from each other- that (given the difficulties of communication in Asia) it is extremely unlikely that the subject's family could have learned anything normally about the previous personality's family before the case developed.

Unfortunately, investigators of cases rarely learn about them before the two families concerned have met. If the subject of a case furnishes information about the previous personality that seems to his parents sufficiently specific (by including proper names of places and persons) and if the distance involved is not too great, the subject's family will usually try to trace the family of which he is talking. They may be impelled to do this by their own curiosity, by the child's strongly expressed wish to go to the other family, or for both reasons. When the families meet, they naturally exchange information about what the subject said concerning the previous life and the extent to which what he said corresponds to facts in the life of a deceased member of the other family. In this exchange members of one or both families may credit the child with having more accurate knowledge about the previous personality than he did in fact have before the families met. This improvement of the case may occur unconsciously and without any intention to deceive. These circumstances make particularly important the rare cases in which someone made a written record of exactly what the subject said before the two families met. Despite our long-standing aware- ness of the importance of such cases they still number only about one percent of the cases admitted to the series documented at the University of Virginia. More exactly, among approximately 2,500 cases someone made a written record of the subject's statements before they were verified in only 24 cases. Reports of three cases of this group in India (Stevenson, 196611974, 1975) and of two in Sri Lanka (Stevenson, 196611974, 1977) have been published.

A means of increasing the number of such cases has been obvious for many years, but has proven difficult to implement. It is to have a person able to identify the cases living in an area where they occur; and that person must quickly reach any case of which he learns and record the subject's statements about the previous life before the subject's parents (or someone else) take the subject to the previous family.

Sri Lanka appears to be a country well suited for such an effort. We have learned of cases there in which the two families had not met that came first to the attention of newspaper reporters. The reporters identified a family corresponding to the subject's statements and often took the subject to that family. They then published a report of the case in a newspaper (which often provided our first information about the case). However, the reporters (with a single exception known to us) were only interested in the immediate news value of the case, and they made no written list of the child's statements before taking him to the other family. Such cases, therefore, could not be included in the small series of these special cases (with written records before verification) that we are trying to increase.

Circumstances finally gave our team a slight advantage over the newspaper reporters in the race to learn first about new cases. Mr. Tissa Jayawardane (T.J.) has been assisting in our research in Sri Lanka for many years. He notified us of new cases that he learned about, and he often accompanied one or both of us on tours to investigate cases. However, his activity on behalf of the research was sporadic and largely confined to the periods when one of us was actually investigating a case. Then in 1985 he unexpectedly became able to devote his entire time to the research. He quickly widened the network of his informants for cases and soon began to learn of many new ones. Some of these were unsolved and probably are insoluble; in others, the two families had already met even before T.J. reached them. Nevertheless, in several instances he reached the scene of the case before the families had met, made a written record of the subject's statements, and then went on to identify a family corresponding to the statements (which family the subject's family had not met or heard about). Our team has now studied four of these cases in Sri Lanka and the present paper reports three of these. (For reasons of space we omit the fourth case here in order to provide sufficient details about the other three.)

These four cases are less than 10% of all the Sri Lanka cases that we have learned about over the period of studying them. At least 50 other Sri Lanka cases have come to our attention during the approximately three years since we learned of the first of these four cases. In all the other cases either the two families had already met by the time we reached the site of the case or the subject had given information that was insufficiently specific to permit tracing a family corresponding to his statements (unsolved cases). It was fortunate for our investigations that in two of the three cases here reported, the families concerned were widely separated geographically; and in the third case, although the families lived much closer to each other, the child's parents were indifferent about the verification of her statements. No report of these cases has been published in a newspaper or magazine. T.J. learned of them through private sources.

Methods of Investigation

Interviews with firsthand witnesses for relevant information are the principal instruments of investigation. On the subject's side of a case the impor- tant informants are the subject's parents, but older siblings, grandparents, and other relatives may provide supplemental information. We always try to interview the subject, but young children vary greatly in their willingness to talk with us. On the side of the previous personality, that person's parents, siblings, and spouse (if the person was married) are the important informants.

We also study any pertinent written documents that are available, but these are rare in Sri Lanka, except for birth and death certificates. In one of the cases that we report here newspaper accounts of the accident in which a previous personality had died provided some confirmatory information. For the same case we examined the report of an inquest.

The investigation of the cases proceeded in the following general manner. When T.J. learned of a new case he went to the family concerned as soon as possible. He obtained an exact address and recorded the main demographic information about the subject. He drew up a list of the subject's statements about the previous life, noting the names of the informants for these. He would advise the subject's family not to try to find the previous personality's family before we had done so. He then notified us about the case. At the same time, if the case seemed solvable, he would go to the place mentioned by the subject and try to find a family corresponding to the statements. If successful in this he would notify us.

As soon as possible thereafter, G.S. would go to the subject's family for more detailed interviews. At this time he would often note statements that the informants had not mentioned earlier to T.J. If he interviewed them before the two families had met, we counted these additional statements in the list of those recorded before verification, even though T.J. had already verified some of the statements that he had recorded earlier. G.S. sometimes also went to the previous personality's family and confirmed the verifica- tions of the subject's statements with them.

In the final stage of the investigation, I.S. (accompanied by G.S. and T.J.) interviewed (sometimes twice) members of both families concerned in the case. Although the informants sometimes mentioned a few additional statements in these later interviews, I.S. concentrated his attention mainly on two aspects of the case: the verification of the subject's statements with the previous personality's family, and the possibilities for some normal communication of information from that family to the subject's.

In making our independent verifications of the subject's statements we always obtained information from two, and sometimes from several, informants for the identified previous family. When visiting them we also exam- ined for ourselves roads, houses, shops, and other details of surroundings that had figured in the subject's statements. These direct observations freed us from dependence on the informants for the verification of these details, although we naturally had to rely on their memories concerning changes in buildings that had occurred after the previous personality's death as well as for information about events in the family life that had figured in the subject's statements.

G.S. acted as an interpreter for I.S., who speaks no Sinhalese, although he can sometimes understand elements of the exchanges between the speaker and the interpreter. Some informants could speak English. All were Sinhalese Buddhists. We rarely use tape recorders, preferring instead to make handwritten notes which record questions asked and answers given by each informant. Details of interviewing techniques have been described else- where (Stevenson, 196611974, 1975).

In the interest of brevity we omit from the case reports that follow many of the details that a complete report of each case would include. For example, we shall only mention the names of informants where doing so would help readers to identify persons referred to more than once. We also omit some details of the subjects' behaviors that related to their statements. Instead, we shall focus attention on the following two features of each case: the key statements made by the subject that were verified as corresponding to events in the life and death of a particular deceased person and the possibilities for the normal communication of information about the previous personality to the subject or the subject's family.

Case Reports

The Case of Thusitha Silva

Thusitha Silva was born near Payagala, Sri Lanka, on July 29, 1981. Her parents were Gunadasa Silva and his wife, Gunaseeli. Gunadasa Silva was a tailor. Thusitha was the sixth of the family's seven children.

When Thusitha was about three years old she heard someone mention Kataragama, and she began to say that she was from there. She said that she lived near the river there and that a dumb boy had pushed her into the river. She implied, without clearly stating, that she had then drowned. (Thusitha had a marked phobia of water.) She said her father was a farmer and also had a boutique for selling flowers which was near the Kiri Vehera (Buddhist stupa). She said that her house was near the main Hindu Temple (Devale)at Kataragama. She gave her father's name as Rathu Herath and said that he was bald and wore a sarong. (Thusitha's father wore trousers.) Thusitha did not give a name for herself in the previous life and indeed gave no proper names apart from "Kataragama" and "Rathu Herath." She never explicitly said that she had been a girl in the previous life, but she mentioned frocks and also objected to having her hair cut; so her parents inferred that she was talking about the life of a girl.

Tissa Jayawardane learned of this case in the autumn of 1985 and visited Thusitha and her family for the first time on November 15, 1985. Having recorded the above statements and some others he went to Kataragama. Here we should explain that Payagala is a small town (population in 1981: 6,000) on the western coast of Sri Lanka south of Colombo, and Kataragama, a well-known place of pilgrimage, is in the southeastern area of the island, in the interior (Obeyesekere, 1981; Wirz, 1966). Kataragama is approximately 220 km by road from Payagala. It is also a small town (population in 1987: approximately 17,500) and consists almost entirely of temples and supporting buildings together with residences for the persons who maintain the temples and supply the needs of the pilgrims. A moderately large river, the Manik Gangs,-runs through the town.

T.J. went first to the police station in Kataragama, where he inquired for a family having a son who was dumb. He was directed to a double row of flower stalls along the pavement of the main road to the Buddhist stupa, known as the Kiri Vehera. (The vendors at these stalls sell flowers to pilgrims for their use in worship.) Upon inquiring again among the flower vendors he was told to go to a particular flower stall, and at that one he asked whether a young girl of the family had drowned. He was told that a young daughter of the family had drowned in the river some years earlier, and one of her brothers was dumb. According to T.J.'s notes, Thusitha had made 13 verifiable statements and all but three of these were correct for the family with the dumb child who had lost a girl from drowning.

In the second phase of the investigation (in December 1985),G.S. learned about 17 additional statements that Thusitha had made, and he recorded these. The two families still had not met (and, so far as we know, this is still true), so that, as mentioned earlier, we consider our record of these statements uncontaminated by any contact between the two families. Two of these 17 additional statements were unverifiable, but the other 15 were correct for the family of the drowned girl. A few of these statements, such as that one of the houses where the family had lived had had a thatched roof, were of wide applicability. A few others, such as that there were crocodiles in the river, could be regarded as part of information generally known about Kataragama. However, several of the additional statements that G.S. recorded were about unusual or specific details, and we will mention these. Thusitha said that her father, in addition to being a farmer and selling flowers, was also a priest at the temple. She mentioned that the family had had two homes and that one of them had glass in the roof. She referred to the water in the river being low. She spoke of dogs that were tied up and fed meat. She said her previous family had a utensil for sifting rice that was better than the one her family had. She described, with imitative actions, how the pilgrims smash coconuts on the ground at the temple in Kataragama.

Western readers unfamiliar with Sri Lanka may not immediately appreciate the unusualness of the details in several of these statements. For example, there are plenty of dogs in Sri Lanka, but most of them are stray mongrels who live as scavengers; few are kept as pets. Also, most Sinhalese who are Buddhists would abhor hunting, although Christian Sinhalese might not. It happened that the family of the drowned girl had neighbors who hunted, and they fed meat from the animals they killed to a dog chained in their compound. This would be an unusual situation in Sri Lanka. Another unusual detail was that of a glass (skylight) in the roof of the house. Devotees at Hindu temples other than the one at Kataragama may smash coconuts as part of their worship; however, Thusitha had never had occasion to see this ritual.

In the third phase of the investigation, I.S. (accompanied by G.S. and T.J.) went to Thusitha's family and then to Kataragama. Each family was visited twice in this phase, once in November 1986 and again in October 1987. We learned that the girl who had drowned, who was called Nimal- kanthi, had been not quite two years old when she died, in about June 1974. Nimalkanthi had gone to the river with her mother, who was washing clothes there. She was playing near her mother with two of her brothers one of whom was the dumb one. Her mother apparently became absorbed in her washing, and then suddenly noticed that Nimalkanthi was missing. The brother who could speak could not say where she had gone. Nimalkanthi's mother raised an alarm, a search was made, and Nimalkanthi's dead body was recovered from the river. It is unlikely that the dumb brother had pushed Nimalkanthi into the water, but all three children had been playing around just before she disappeared. It seems probable that she lost her footing and slid or fell into the water; she could not swim. Thusitha's statement that the dumb brother had pushed her into the river thus remains unverified, and it is probably incorrect. However, the brother may have pushed her playfully just before she drowned accidentally.

Two of Thusitha's verifiable statements were definitely incorrect. She said that her father of the previous life was bald, but Nimalkanthi's father (whom we interviewed) had a good head of hair. She said his name was Rathu Herath, but it was Dharmadasa. There were, however, two bald men in the family- Nimalkanthi's maternal grandfather and a maternal uncle- and Nimalkanthi would have seen them often. And a cousin by marriage, whom Nimalkanthi saw from time to time, was called Herath (not Rathu Herath). Thus one could argue that Thusitha's memories included some confusions of the adult men in her family, but we do not wish to emphasize this explanation.

Another of Thusitha's statements was incorrect for Nimalkanthi's life- time, but not for the period after her death. She said that she had sisters (but did not say how many). Nimalkanthi had one sister, and about 18 months after her death, her mother gave birth to another daughter.

Concerning the possibilities for previous acquaintance between the families concerned, we are confident that they had none. Nimalkanthi's family had never even heard of Thusitha when we first met them. Nimalkanthi's father had never been to Payagala; he had passed through it only on his way to a larger town called Kalutara, also on the west coast of Sri Lanka. Thusitha's family had never gone to Kataragama in an effort to verify her statements. Gunadasa Silva said he had hoped to do this, but for various reasons- largely the needs of his tailoring business- he had never got around to this.

In the years 1980-81 Gunadasa Silva had gone "very often" to Kataragama. On one visit only, when she was two months pregnant with Thusitha, his wife, Gunaseeli, had gone with him. Gunadasa had bathed in the river in the usual way of pilgrims and had purchased flowers from the flower stalls near the Kiri Vehera. He could not remember the name- if he ever knew it- of the flower vendor from whom he purchased most of the flowers he bought. Thus he had gone to Kataragama after Nimalkanthi's death, but had stopped going there before Thusitha's birth. Thusitha, incidentally, said that she had seen her father at Kataragama, a reference on her part to a presumed discarnate existence between the death of Nimalkanthi and her own birth [Most children who claim to remember previous lives say nothing about events after death in the previous life and before their birth. Memories of a discarnate existence are particularly rare in Sri Lanka cases. The case of Disna Samarasinghe (Stevenson, 1977) is exceptional. When the children do make comments about such "intermediate(7)' experiences, they frequently include the child's explanation of how it came to be in its family, instead of in some other family.]

We made inquiries in Kataragama about the frequency of drownings in the river. The police station had records available only for the three years of 1985-87. There had been one drowning in 1985, none in 1986, and one (up to October) in 1987. The coroner of Kataragama had died in 1986 and his records were not available. The coroner of the neighboring town of Tissamaharama, who had been acting coroner at Kataragama for almost a year (since the death of its regular coroner), had no detailed figures of drownings in the river at Kataragama; however, he estimated that one occurred about every two years, mostly among pilgrims. The registrar of births and deaths at Kataragama did not keep records beyond each year, at the end of which the records were sent to the government office (kachcheri) of the next largest administrative area. The records were not classified according to causes of death. The registrar said that there had been no drownings so far in 1987 (contrary to the police records). She estimated that two children drowned in the river each year, a much higher estimate than other sources suggested.

There were 20 stalls of flower vendors on either side of the broad avenue that leads to the Buddhist stupa (Kin Vehera) in Kataragama. On the day of our inquiries one stall was unattended, but we asked the vendors at all the others whether any member of their family was dumb and whether any member had drowned. One vendor's family had a cousin who was dumb; no other family (apart from Nimalkanthi's) had any dumb member. No family except Nimalkanthi's had lost a member through drowning.

Comment. Despite Thusitha's failure to state correctly any proper names other than that of Kataragama, we have no doubt that we have identified the only family to which her statements could refer. The single detail that her (previous) father had a flower stall near the Kiri Vehera in Kataragama immediately restricted the possibilities to about 20 families. Of these, only one had both a son who was dumb and a daughter who drowned in the river. The various other details Thusitha mentioned are hardly necessary for in- creasing the correctness of the identification of the family to which Thusitha's statements correspond, although they do provide additional confirmation.

The Case of Iranga Jayakody

Iranga Jayakody was born in Uragasmanhandiya, Sri Lanka, on June 29, 1981. Her parents were M.H.P. Jayakody and his wife, Nimali. Iranga's father was a schoolteacher and an astrologer. She was the seventh and youngest child, and also the only daughter, in the family. Uragasmanhandiya is a small village (population estimated in 1987: 3,100).

When Iranga was between three and four years old she began to talk about a previous life that she said she had lived in Elpitiya, a small town (population estimated in 1987: 6,200) located about 15 km from Uragasmanhan- diya. Her family had neighbors one of whom was from a place called Matugama, and Iranga seems to have been first stimulated to talk about the previous life when she heard the neighbor referring to Matugama. She then said that she had had (meaning in a previous life) a mother who came from Matugama. After this, she gradually made a large number of statements concerning the life she claimed to remember. These statements included details of events in the family life, descriptions of the family's house and its surroundings, and the description of a shop where bananas were sold that the previous personality's father had owned. She said that she had three sisters, one of whom was married. She said that she had been attending a school that was much larger than her present school. At the school she wore a white uniform, but changed into other clothes when she came home from school and studied. She mentioned only one personal name (which remains unverified) and only one place name additional to Elpitiya. This was Matugama, the town from which her (previous) mother came. She did not men- tion how she had died in the previous life. Iranga also showed several traits of behavior that were unusual in her family and that were subsequently found to correspond with behavior that the subsequently identified previous personality was known to have shown or that would have been appropriate for her. The most remarkable of these behaviors was an extreme modesty about any exposure of her body, especially her breasts, which she first showed when only three years old.

In December 1985, T.J. learned about the case. In the same month he visited Iranga and her parents and recorded a list of 18 statements that her parents remembered Iranga had made about the previous life. In February 1986, Iranga went to Elpitiya with her family to attend a wedding, and while there she pointed toward a road and said it was the way to her previous house. However, her parents had no time then and no interest in pursuing the matter, so they brought Iranga home, somewhat disappointed.

In July 1986, T.J. went to Elpitiya and from his list of Iranga's statements he provisionally identified a family corresponding to them. He did this by inquiring among the vendors of bananas whether any had lost a daughter of school age. T.J. interviewed four of the members of the family and verified all but two of the statements he had recorded from Iranga's parents. The parents of the family had died, and his informants were brothers and sisters of the candidate previous personality.

On August 11, 1986 G.S. and T.J. interviewed Iranga's parents again and recorded another 25 statements not previously recorded by T.J. (and proba- bly not earlier mentioned to him). They then went to Elpitiya and inter- viewed a member (Podi Haminie) of the family T.J. had earlier identified as the one correctly corresponding to Iranga's statements.

This family had lost a daughter, Punchihamie, who had died on May 5, 1950, at the age of 13. Punchihamie had been ill for a year or more before her death and had been paralyzed on the left side of her body. Doctors in Colombo had diagnosed a brain tumor and proposed an operation, but she was taken home and died there. (We remain uncertain about whether the family had refused an operation or whether the doctors considered the tumor inoperable when they first diagnosed it.) In a further interview with Punchihamie's younger sister, Podi Haminie, G.S. verified nearly all of Iranga's statements.

The following day (August 12, 1986) G.S. and T.J. took Iranga to Elpitiya (with her parents) with a view to seeing whether she could recognize people and places there. Iranga seemed to recognize the old road or path from the highway to Punchihamie's house (not then much used, because a new, wider road provided easier access to the house). However, at the house she did not clearly (or even vaguely) recognize anyone or any object with which Pun- chihamie had been familiar. She seemed comfortable in the (for her) strange situation, but not familiar with it in a specific way.

In the third phase of the investigation, I.S. (accompanied by G.S. and T.J.) visited both the families on November 3-4, 1986. We then gave particular attention to the possibilities for normal contact between the families concerned and to the verifications of Iranga's statements. For the verifications we interviewed again two of Punchihamie's sisters, Podi Haminie and Emalinnona. In October 1987, we had another interview with Iranga's mother; and we also visited Elpitiya again, mainly to determine the number and location of the banana vendors.

T.J. and G.S. had recorded (before the two families met) 43 statements Iranga's parents said she had made about the previous life. Of these two were incorrect and three unverifiable or doubtful. One other statement was not literally correct, but could be considered correct from the perspective of a Sri Lanka child. Iranga had said that her younger sister had a bicycle. This was not true of Punchihamie's real younger sister, Podi Haminie. However, the daughter of a neighbor had a bicycle and Podi Haminie played with it. Also, the neighbor's daughter, whose bicycle was played with, was known to Punchihamie's family (in the manner of Asians) as "younger sister." The elimination of these six statements that were wrong, unverifiable, or doubt- ful left 37 statements all of which were correct for Punchihamie. Some of these might have applied to many village homes in Sri Lanka. This would be true for example, of Iranga's references to a Jasmine creeper and Jak trees at the house. However, many other statements had a much more restricted applicability, and although no single one of them was decisive, taken to- gether they convinced us that Iranga was talking about Punchihamie's life and no one else's.

We will now describe the more important of Iranga's statements that, in our view, specified the family and the person of whom she was speaking. We begin with the fact that Elpitiya is a small town with only two main streets, which are both continuations of highways through the town. We found six boutiques (as small shops are known in Sri Lanka) that sold bananas and learned of three more that had formerly sold bananas, but no longer did so. These were among about 100 boutiques extending along the main roads. The choice among the owners of these few boutiques where bananas were sold became further narrowed by the requirement that the owner have married a woman from Matugama and have had four daughters of whom one had married. Further, Iranga said that the family lived in a house approached along a road through a jungle with rubber and cinnamon trees, and it was both near the boutique and near a temple; the house had red walls and a kitchen with a thatched roof; and a well of the family had been destroyed by rain, but the family still had two other wells, one for washing and drinking and one for bathing. Iranga, in addition to stating, as men- tioned, that she had attended a large school to which she went wearing a white uniform from which she changed on returning home, also said that she had attended a Buddhist Sunday School. She had gold earrings given to her by her father and wore her hair in two plats. She was a middle sister and had a younger sister. All these details were correct for Punchihamie and her family.

Iranga referred correctly to several features of the boutique and house that had been present during Punchihamie's life, but were subsequently changed. For example, the boutique where bananas were sold had had a roof of coconut leaves, but later the roof was changed to one of tile. The walls of the house had been red, but were subsequently painted white. The kitchen had had a thatched roof, but its roof was later tiled also.

We shall next mention and briefly discuss three of Iranga's statements that are unverified or doubtful. She referred to someone called Wijepala. No one in Punchihamie's family could place with certainty a person of that name, although Podi Haminie thought Wijepala might have been the name of an employee. Iranga also referred to her older sister and her mother going to the hospital and returning with a "younger sister." It happened that during Punchihamie's life both her mother and her older sister had given birth to daughters. Both of these baby girls would have been regarded by Punchihamie as " younger sisters." It is possible that Iranga had fused mem- ories of these two births. Iranga said that she had gone to village fairs with her mother. This was correct, but she also said that (on one occasion) she could not find her mother at the fair and then found herself in her (present) family. When we asked Podi Haminie whether Punchihamie had ever been lost at a fair, she could not remember such an episode. She then thought she remembered (without certainty) that Punchihamie had gone to a fair by herself and had there become ill. This was the onset of the illness from which she subsequently died. However, Punchihamie's older sister, Emalinnona, remembered that Punchihamie had first become ill when at school, where she had fainted or collapsed.

Members of the two families concerned in the case had not known each other before the case developed. Iranga's mother said that their family had no connections with Elpitiya; they did their shopping in Uragasmanhandiya. However, Iranga's father had visited patients in the hospital at Elpitiya, and he had sometimes stopped briefly in Elpitiya on his way to other places to which he would travel by bus. Also, Iranga's family had attended a wedding in Elpitiya, so they evidently had some acquaintances there. This does not mean that they knew or knew about Punchihamie's family, and it seems extremely unlikely that they did. That they were unacquainted with Punchihamie's family seems further shown by their indifference to Iranga's effort, when they were in Elpitiya for the wedding, to show them the way to the house where she said she had lived in the previous life. If they had recognized the road as one on which someone they knew lived, they would have remembered this later.

Punchihamie's father had had a relative in Uragasmanhandiya, and he went there sometimes to visit the relative. Also, there had been a well-known monk at Uragasmanhandiya who reputedly had healing powers, and sick persons were sometimes taken to him for healing. Punchihamie's family had taken her to this monk in Uragasmanhandiya only a few weeks before she died. (At that time Iranga's family were still living in Ampurai, far away in the east of Sri Lanka.) Punchihamie's younger sister, when she learned about Iranga, became eager to meet her, and if she had known about Iranga and her family before we brought the two families together, she would certainly have gone to Uragasmandhandiya and met them. We asked Ir- anga's father whether, when the two families had met, they discovered that they had had mutual friends or other connections, and he said that they had not. There might have been occasions when they happened to be at the same place at the same time in Elpitiya, such as at the bus stand or at the hospital, but this does not mean that they knew each other or had ever formally met. To summarize, our inquiries showed that each family had some acquain- tances or relatives in the community of the other family and each had visited the other community; but we are satisfied that they had not known each other before the case developed.

Comment. Many of Iranga's statements taken one by one could apply to a number of families in Elpitiya. Among the sellers of bananas originally questioned by T.J., only two had lost daughters. However, one of these had lost two daughters who were under school age and Iranga had spoken about attending school, as Punchihamie, the daughter of the other banana seller, had done. The identification is additionally further specified by many of Iranga's other statements. When we add detail after detail the collective applicability of all her statements to other persons becomes steadily reduced until it becomes clear that Iranga was talking about the life of Punchihamie and no one else.

The Case of Subashini Gunasekera

Subashini Gunasekera was born in the hospital at Madampe, Sri Lanka, on January 13, 1980. Her parents were M.G.M. Gunasekera and his wife, Podi Menike. They were both schoolteachers. Subashini was their second daughter and fourth (and youngest) child. From before the time of Subashini's birth the family lived in Kuliyapitiya, which is a small town (population in 1987: approximately 5,000) in the western central area of Sri Lanka about 35 km from the west coast. By road it is about 75 km west and slightly north of Kandy.

When Subashini was about 3 years old, she began to speak about a previous life. She said that she had been " trapped" when a hill fell on her house and that this had happened at Sinhapitiya, Gampola. She gave some details of the family she was remembering,including that she had an older brother, an older sister, a younger brother, and a younger sister. She referred to someone called Vasini who was where she lived, but she did not state who Vasini was; and she did not give a name for herself in the previous life. Gradually she mentioned other details, such as that her family worked on a tea plantation, where her mother and brother plucked tea, and where they had a water tap that could not be fully closed off. She said that when the hill began falling it made a sound like "Gudu, Gudu." Her mother, she said, called her and asked her to take a torch (flashlight)and go out to see whether the hill was coming down on the house. She said that then she was "trapped" and came to her (present) family with the torch.

Gampola is in the highlands of Sri Lanka about 20 km south and slightly west of Kandy and therefore about 95 km by road from Kuliyapitiya. Sinhapitiya is also a small town (population in 1987: approximately 5,000) about 1 km south of Gampola. Subashini's mother had close relatives in villages in the area of Gampola. An older sister lived 10 km from Gampola and an older brother about 15 km from it. She and her husband visited these relatives at least once a year. Podi Menike heard about a landslide at Sinha- pitiya in 1977, soon after it happened, but she learned no details about it and read no newspaper report of it. She must not have mentioned the matter to her husband, because M.G.M. Gunasekera said that he had known nothing about a landslide at Sinhapitiya until Subashini began talking about one.

When Subashini was about three years old, her parents attended a wed- ding in the region of Gampola and Subashini accompanied them. Subashini's father told his in-laws about her statements referring to a previous life. Podi Menike's brother-in-law remembered that some years earlier there had been a landslide at Sinhapitiya with some deaths. Thinking to learn more about the accuracy of Subashini's statements, her father took her along a road on the tea estate where, he had been told, the landslide had occurred. However, Subashini became frightened, screamed, and refused to go on, saying that she was afraid of being " trapped." M.G.M. Gunasekera therefore turned back and did not meet any of the families who had lost members in the landslide. Subsequently, he wrote to his wife's older brother and asked him to make further inquiries. His brother-in-law verified that there had been deaths of workers in the landslide, that the deaths had included members of a Sinhalese family who had been living in "lines" (as described by Subashini), and that a son of the family had been working in a shop in Gampola. That was the sum of all that M.G.M. Gunasekera had verified before we reached the scene of the case. He appeared to have lost interest in it, because he had discontinued his inquiries.

T.J. learned about the case in late 1983, and he first visited Subashini and her family on November 24, 1983. At that time Subashini was not quite four years old, and as she was still speaking about the previous life, he recorded 10 statements directly from her. (Other members of her family subsequently corroborated that she had been stating these details earlier.)

T.J. sent the list of Subashini's statements to us. He also sent a photocopy of a newspaper report of a landslide at Sinhapitiya that was published (three days after the landslide) on October 25, 1977 in the Ceylon Daily Mirror. (This included a photograph of caskets containing the bodies of some of the victims buried in the landslide.) Here we shall digress to describe the land- slide briefly. Our information about it came mainly from surviving members of one of the families whose houses were destroyed, from one of their neighbors, and from the ownerlmanager (I.B. Herath) of the tea estate on which the landslide occurred. The newspaper report mentioned above (and another that we obtained subsequently) also provided information as did a copy of the inquest that we examined. The landslide occurred on a high hill near the upper limits of a large tea estate. Heavy rains had been falling and in the early evening- estimates of the time varied between 7:30 p.m. and 8:30 p.m.- the earth with heavy rocks above a line of workers' houses began falling and quickly completely covered the houses and their occupants. It took some days to recover all the bodies. One informant said that 17 persons had died, but the estate's ownerlmanager said 28 persons had died. They had all been living in a line of small houses (called "lines") where the workers on the plantations lived. As it was evening, many of the residents were in the houses when the landslide occurred.

To return to our investigation of the case, during 1984-85 we did little fieldwork in Sri Lanka, and it was not until May 1986 that we resumed work on this case. In that month G.S. went twice to Sinhapitiya. He first met I.B. Herath, the ownerlmanager of the tea estate on which the landslide had occurred, who then arranged for G.S. to meet a surviving male member of one of the families whose houses had been covered by the landslide. This man was H.G. Piyasena, and he verified the accuracy of most of Subashini's statements for the life of his younger sister, Devi Mallika, who, with four other members of their family, including both their parents, had died in the landslide on October 22, 1977. H.G. Piyasena had himself been away from the house at the time, and so he had escaped; accordingly, he could not verify Subashini's statement that when the landslide began, her mother asked her to take a torch and see whether the hill was coming down.

In the next phase of our investigation (August-September 1986)' G.S. interviewed both of Subashini's parents and recorded an additional 22 items that Subashini had stated about the previous life. He then arranged for Subashini and her parents to go with him and T.J. to Sinhapitiya, where they were to meet members of Devi Mallika's family at the home of the tea estate's ownerlmanager. There Subashini recognized H.G. Piyasena by call- ing him "older brother," but she failed to recognize Mallika, Devi Mallika's older sister, and a neighbor of the family, R.W.K. Banda, who had known Devi Mallika well. (Subashini's recognition of H.G. Piyasena was marred, because he pushed himself forward from a group and stood in front of Subashini; G.S. then asked her "Who is he?" Thus, although she had no verbal clue to his identity, she might have inferred that he was an older

232 I. Stevenson and G. Samararatne

At the time of this meeting, G.S. went over the complete list of Suba- shini7s recorded statements, which now contained 32 items. He found that all but seven of these were correct for the life of Devi Mallika. Devi Mallika's older brother and sister provided most of the verifications, but R.W.K. Banda also contributed some information.

The party consisting of Subashin's family, G.S., and T .J. took the car that had brought them to Sinhapitiya along the road leading toward the upper levels of the tea estate. They reached the place where Subashini had earlier reacted with fear so that her father had had to bring her away. On this second occasion- three and a half years later- she showed no fear; she also did not seem to recognize any place along the way. The car could not go to the site of the landslide and the party turned back.

In November 1986, I.S. (accompanied by G.S. and T.J.) met Subashini and her parents at Kuliyapitiya. We went over some of the main features of the case again and learned more about Podi Menike's relatives who lived in villages near Sinhapitiya. We then went to Sinhapitiya (near Gampola) and continued the investigation there. It seemed important for us to examine the site of the landslide for ourselves. This required walking uphill for about 4 km from where the estate's jeep could take us no farther. At the site of the landslide and on a neighboring hill we met again Devi Mallika's older brother, H.G. Piyasena, and her older sister, Mallika. H.G. Piyasena took us to the site of the landslide. Abundant vegetation had completely covered the area and no trace of the destroyed line of houses remained. However, H.G. Piyasena showed the sites of some details that Subashini had mentioned. From examining the steep terrain, we could easily imagine how the land- slide had occurred. We also saw some of the typical residential lines where laborers on the estate lived and received a vivid impression of the extreme poverty of the families living in these tiny, squalid houses. In this case, far more than in most Sri Lanka cases, the two families were separated widely in their socioeconomic statuses.

In Gampola we examined and copied part of the inquest into the deaths of persons who had lost their lives in the landslide.

In October 1987 we had another interview with Subashini's parents and we went again to the area of Gampola. On this occasion we met and inter- viewed Podi Menike's sister, brother-in-law,and brother. We also obtained additional information about the occurrence of landslides with deaths in the area of Sinhapitiya.

We mentioned above that all but seven of Subashini's statements were correct for the life of Devi Mallika. The seven exceptional statements were unverifiable or wrong; we think five of them deserve brief mention and discussion. Two of them were the statements mentioned earlier referring to the previous mother having asked her to take a torch and see whether the hill was coming down on the house. From lack of eyewitnesses these remain unverified but are plausible. The house had no electricity and the family used torches at night; also, Devi Mallika was the oldest of three children in the house at the time and so the one likely to have been asked by her mother to see what was happening. We were also unable to verify a reference that Subashini made to an older brother having come home shortly before the landslide and then gone out again to have his supper elsewhere. One of Devi Mallika's older brothers, Chandrasena, had come home at that time. He then left the house after his father asked him to request another older brother to come to see him; thus Chandrasena escaped being killed in the accident. He had not left the house, so far as we could learn, because his supper was not ready; but it was possible that Subashini had a somewhat muddled memory of this older brother. (We have not yet been able to meet him.) Subashini also referred to an "uncle" who was strict, and he could not be identified. It is just possible that Subashini was referring here to R.W.K. Banda, the neighbor we mentioned earlier. Devi Mallika might have re- garded him, in the Sri Lanka manner, as an "uncle." He was in the police force, and Devi Mallika might have associated his occupation with strictness and therefore thought of him as strict. Also, although he was friendly and even affectionate with her, he would sometimes tease her by pretending to be strict. The fifth statement of this group may perhaps be explained as an example of confusion between two closely similar Sinhalese words. Suba- shini had said- or had been thought by her older brother to have said- that the previous house was near a waterfall. This was not true of Devi Mallika's house, but there was a stream nearby. The Sinhalese word for stream is ala and that for a waterfall is dialla, hence the possibility of a confusion. (We discuss below an eighth item, a name Subashini mentioned, which is inex- act, although we have counted it as correct.)

Subashini used some words and phrases that were not current in her family, but appropriate for the life that she seemed to be remembering. For example, she referred to the previous father by the low country word

Thatha, whereas she addressed her father as Apachie, using the word cus- tomary with the Kandyan (up country) Sri Lankans. Devi Mallika had addressed her father as Thatha. In referring to the row of houses called lines, in which laborers on tea .estatesare housed she referred to line kamera and lime. Both these terms are used by the residents of the tea estates to refer to these lines of houses. (The word lime [in this context] may be a sort of collapsed fusion of line kamera or it may derive from the Tamil word layam, which means a horse stable.)

We will next describe the reasoning we followed in deciding that Subashini was talking about the life of Devi Mallika and not that of some other person. Subashini had mentioned " the hill coming down" (an obvious refer- ence to a landslide), and she said that she was from Sinhapitiya, Gampola. From I.B. Herath, who had lived in Sinhapitiya all his life (being then 36 years old), from newspaper correspondents of the area south of Kandy, and from two "old-timer" townsfolk whom we interviewed, we ascertained that for the previous 25 years and probably for much longer, there had been only one major landslide with fatalities at Sinhapitiya, that of October 22, 1977. In that accident, however, Devi Mallika was one of the perhaps 28 persons who were killed, and we need to show how we could decide that Subashini was talking about her life and not that of another person killed in this accident. It happens that although there were about eight houses in the lines destroyed in the landslide, all but one of these were occupied by Tamils (2) . Subashini had made it clear that her family were Sinhalese. She had mentioned Tamils living in the lines, and then some of her siblings had teased her about being a Tamil; this had made her angry, as it would not have done

if she had been remembering the life of a Tamil. A further clue for this detail came from Subashini's statement that there had been a Buddhist Temple in the area where she had lived. Sinhalese people are mostly Buddhists, although some are Christians; Tamils are nearly always Hindus. Subashini was therefore referring to the single Sinhalese family living in the residential lines covered by the landslide. In that family, there were 11 children, although they were not all living at home at the time of the accident. In fact, only the three youngest children- two girls and a boy- were in the house with their parents when the accident occurred. These three children and their parents were all killed. Subashini mentioned the father and mother of the previouslife and made (correct)descriptive remarks about them, such as that the previous father had a big belly and that the previous mother was larger than her mother. Some of her other remarks, such as references to a blue frock and to a kite (both of which Devi Mallika had), also clearly pointed to the life of a female child of the family, not that of one of the adults. Devi Mallika was the oldest of the three children killed and the only one of them who could say, as Subashini did, that she had a younger brother and a younger sister. She had also given the name of Vasini, not as that of herself in the previous life, but as that of a girl who was perhaps a member of the family. We think the name "Vasini" was Subashini's modified recollection of the pet name of Devi Mallika's younger sister, the baby of the family, who was one and a half years old at the time of the landslide. This child's given name was Chandrakanthie, but her pet name was Vasanthie. This name is closely similar to Vasini. We have no doubt, therefore, that Subashini was speaking about the life of Devi Mallika and no one else. Devi Mallika was about seven years old when she died.(3)

---------------------

1.The Sinhalese for centuries were independent cultivators and they did not like to become employees of other people. For this reason the British tea planters of the 19th century brought Tamils from India to work on the highland tea estates. Even at the present time Tamils are the principal laborerson the tea estates, and it is somewhat unusual to find Sinhalese among them.

2. We obtained estimates of Devi Mallika's age at her death that varied widely between a low of three and a half years and a high of seven years. (One of the coroner's records gave her age as four years, but the information for this may have derived from an uninformed neighbor of the family; another of his records gave her age as seven and noted that this information came from her older sister.) We have adopted the age of seven on which Devi Mallika's older sister, Mallika, and the family's neighbor, R.W.K. Banda, agreed.

--------------------

In addition to her statements about the previous life that provided clues to the identification of the previous personality, Subashini made other remarks and showed behavior harmonious with the life of a poor family living on a tea estate. She was able to describe tea bushes, which she could never have seen in the area where her family lived; it has a distinctly different vegetation from that of the region around Gampola. She commented that her younger brother was given more milk than she, which indicated a life in poverty as did her habit of taking with her tea only a small amount of sugar on the palm of her hand from which she licked it up. (Devi Mallika's older sister, Mal- lika, said that this was the practice in their family because they could afford so little sugar.) Devi Mallika was particularly fond of her father and slept with him more often than with her mother. Subashini similarly preferred to sleep with her father. Subashini also had a marked phobia of thunder and lightning; the other children of the family had no such phobia.

To conclude the report of Subashini's case we shall mention again the relatives of Subashini's mother, Podi Menike, who lived in villages in the general area of Gampola. Devi Mallika's family had relatives in two villages of this area, and she had been taken there. It is possible that after her death some of her family were in this area at times when Subashini's parents were also there. One may suppose that Subashini's parents or Subashini herself overheard Devi Mallika's relatives talking about the landslide of 1977. If this happened, the occasion would not have been a social one because of the wide disparity in social status between the families. Moreover, we do not believe that Subashini or her parents could have assimilated 25 correct details about a strange family without her parents later remembering at least some of these.

Devi Mallika's family had no connections with Kuliyapitiya, and we can confidently exclude the possibility that Subashini and her family would have learned about Devi Mallika in the area where they lived.

Comment. This case requires less comment than the preceding two. The subject said she remembered a landslide that was unique in a place that she named. She gave details about a family and a daughter of that family that could apply to only one person, a girl who had perished in the landslide.

Summary of Statements by the Three Subjects

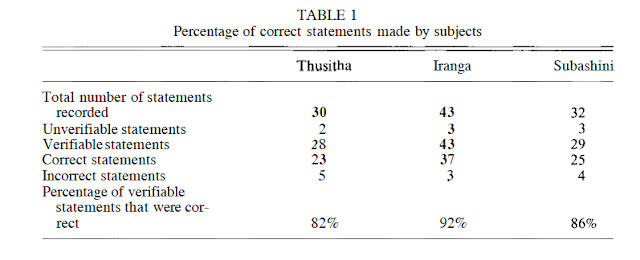

We have summarized in Table 1 the statements each subject made, and we have stated the percentage of verifiable statements that were correct. Although we have not conducted a systematic exarci.nation of the accuracy of the children's statements in cases of this type, we believe that other subjects whose cases we have investigated showed similar levels of accuracy. We should emphasize, however, that the identification of a deceased person corresponding to a child's statements depends on the specificity of the statements more than on their number. A few specific statements having restricted applicability, such as proper names, may suffice for correct identification when many statements of wide applicability would not.

Discussion

Before discussing the particular strength of the three cases here reported, we wish to place them in the larger context of investigationsof cases of this type. Among the approximately 180 cases that we have investigated in Sri Lanka these three cases are among the strongest in the evidence they provide of some paranormal process. However, some other cases are as strong as these three, or even stronger. We think readers can best appraise the strengths of these cases by studying reports of a number of them together- certainly more than three only- and we hope the present paper will stimulate readers unfamiliar with these cases to examine some of our other reports of them and a general survey of this research that I.S. has published (Ste- venson, 1987).

None of the three subjects of these cases stated the name of the person whose life they seemed to recall. Indeed, as is almost the rule among Sinhalese subjects, they mentioned few personal names of any kind.(4) However, they all mentioned the names of the places where the previous life had occurred, and they all gave sufficiently specific additional details so that it was possible to identify a deceased person- in each case another child- whose life and death corresponded to the subject's statements.

---------------

4. In their daily intercourse with each other- even within families- Sinhalese people do not much use personal names in speaking with each other. One of us has offered elsewhere further observations on this habit, which is almost a phobia of using personal names (Stevenson, 1977). Whatever its origin, the reluctance to use personal names probably has a bearing on the infrequency with which the subjects of cases in Sri Lanka include such names among their statements about previous lives they seem to be remembering.

--------------

An important point is whether- given the children's failure to mention personal names- their statements might have applied equally well to other deceased children. We think they do not, but we have tried to furnish enough detail so that other readers may form their own opinion on the matter. A second and equally important point is whether the subjects might somehow have obtained the correct information they showed by normal means, and we think that we have shown that in these cases this is extremely unlikely if not impossible. We feel warranted therefore in concluding that the subjects of these three cases had all obtained detailed knowledge about a particular deceased person by some paranormal process.

During the nearly 30 years that have passed since the systematic investigation of these cases began, a variety of interpretations for them have been put forward, both by us and by other persons who have read our reports. The leading interpretations are: fraud, cryptomnesia (source amnesia), unintentional distortion of memories on the part of the informants (paramnesia), extrasensory perception on the part of the subject, possession, and reincarnation. We shall not review the arguments for and against each of these interpretations. Interested readers may study full discussions of them elsewhere (Stevenson, 1966/1974, 1975, 1987). Suffice it to say here that although each of the interpretations that are alternative to reincarnation may be correct for a few cases, all but one break down when applied to most of the cases. The exceptional interpretation, however, is extremely difficult to exclude. We refer to that of paramnesia, which means that, without being aware that they have done so, the informants for the families concerned in a case have so muddled their memories of what the subject said and of what was true about the identified deceased person as to vitiate the case. This possibility has become further elaborated into what we may call the sociopsychological interpretation of the cases. According to it, in a culture having a belief in reincarnation a child who seems to speak about a previous life will be encouraged to say more. What he says then leads his parents somehow to find another family whose members come to believe that the child has been speaking about a deceased member of their family. The two families exchange information about details, and they end by crediting the subject with having had much more knowledge about the identified deceased person than he really had had. Chari (1962, 1987) has been a particularly articulate and long-standing exponent of this interpretation. Brody (1979) gave a succinct as well as a fair exposition of it.

Because we recognize the plausibility of the sociopsychological interpretation, at least for some cases, we attach great importance to the cases of the present group: ones in which someone (ourselves preferably) makes a writ- ten record of the subject's statements before they are verified. As mentioned in our Introduction, the present three cases belong to a still small group of 24 cases. However, our recent success in finding the present cases encourages us to think that we can find other cases of the type. Their investigation should assist considerably in reducing the number of possible interpretations of cases suggestive of reincarnation.

Conclusions

In three cases of children (in Sri Lanka) claiming to remember previous lives, written record's of the children statements were made before they verified. It was possible in each case to find a family that had lost a member whose life corresponded to the subject's statements. The statements of the subject, taken as a group, were sufficiently specific so that they could not have corresponded to the life of any other person. We believe we have excluded normal transmission of the correct information to the subjects and that they obtained the correct information they showed about the concerned deceased person by some paranormal process.

References

Barker, D. R., & Pasricha, S. K. (1979). Reincarnation cases in Fatehabad: A systematic survey in North India. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 14, 231-240.

Brody, E. B. (1979). Review of Cases of the reincarnationtype. Volume II. Ten Cases in Sri Lanka. By Ian Stevenson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 167, 769-774.

Chari, C. T. K. (1962). Paramnesia and reincarnation. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research,53, 264-286.

Chari, C. T. K. (1987). Correspondence. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 54, 226- 228.

Cook, E. W., Pasricha, S., Samararatne, G., U Win Maung, & Stevenson, I. (1983). A review and analysis of "unsolved" cases of the reincarnation type. 11. Comparison of features of solved and unsolved cases. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 77, 115- 135.

Obeyesekere, G. (1981). Medusa S hair. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pasricha, S. K., & Stevenson, I. (1987). Indian cases of the reincarnation type two generations apart. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 54, 239- 246.

Stevenson, I. (1974). Twenty cases suggestive of reincarnation.Charlottesville: University Press

of Virginia (2nd rev. ed.). (First published in Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research, 26, 1- 362, 1966.)

Stevenson, I. (1975). Cases of the reincarnation type. I. Ten cases in India. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1977).Cases of the reincarnation type. II. Ten casesin Sri Lanka. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1980). Cases of the reincarnation type. III. Twelve cases in Lebanon and Turkey. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1983). Cases of the reincarnation type. IV . Twelve cases in Thailand and Burma. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1987).Children who remember previous lives: A question of reincarnation.Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Wirz,P.(1966).Katagarama:The holiest place in Ceylon (D.B.Pralle,Trans.).Colombo:Lake House Publishers.

No comments:

Post a Comment