PYRAMIDS AND GEOPOLYMERS

BOOK: THE PYRAMIDS AN ENIGMA SOLVED

Prof. Joseph Davidovits

Chapter 14

The Rise of Pyramids

Pyramid construction methods pose great questions. The work that would be involved using the accepted method is staggering, even with modern machinery; and with the construction method eluding historians, reasons for the rise and decline of pyramid building are misunderstood.

In general, Egyptologists advocate that early pyramid building put an intolerable burden on manpower and the economy, causing the decline. This explanation fails to address the reason why pyramid building was not at least attempted during certain later wealthy dynasties possessing additional territory, masses of slaves, better tools, and executing prolific building projects.

The reasons for the rise and decline of pyramid construction crystallize when one considers the developments associated with the use of agglomerated stone. The developments in construction parallel those of the modern concrete industry after the introduction of Portland cement; specifically, the first pyramid blocks weighed only a few pounds. Their size gradually increased over the pyramid- building era to include enormous blocks and support beams weighing up to hundreds of tons apiece. If the pyramids were built of carved blocks, the observed evolution of pyramid construction would be highly unlikely. An overview clarifies these points.

Figure61: Sphinx and the Great Pyramid. Figure 62: The pyramids are situated in the necropolis on the West Bank of the Nile.

The pyramid of Pharaoh Zoser served as a prototype for following Third Dynasty pyramids. Because Third Dynasty history is obscure, with the number and order of reigns still debated, the identification of the pyramids immediately following Zoser’s is tenuous. Tentatively among Zoser’s Third Dynasty pyramid-building successors were pharaohs Sekhemkhet, Neb-ka, and Kha-ba. None of these kings reigned long enough to complete his monument.

The pyramid considered second in chronology is attributed to Zoser’s successor, Sekhemkhet, who is believed to have reigned from six to eight years. This complex is located at Saqqara near the original pyramid and was planned along a similar design. The intent to build a larger monument is apparent from a larger enclosure. This unfinished monument is in ruins. Only two tiers remain.

One distinctive architectural feature found inside is a door framed by an arch. If this pyramid were correctly dated to the Third Dynasty, the arch would most likely be the earliest ever constructed. Nearby, several Ptolemaic mummies were discovered in the sand. Also discovered were objects dating from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and later During the Twenty- sixth Dynasty old traditions were revived. A chamber inside the pyramid, which was first entered during excavation in the 1950s, showed signs of previous entry even though almost 1,000 items of gold jewelry had not been removed from the adjoining passageway.

Construction ramps were found in situ. These ramps do not provide evidence for the hoisting of enormous blocks for the Great Pyramids because the blocks of this structure are small. If this pyramid is correctly dated to the era when stone was agglomerated, the blocks were manufactured near the site in numerous small wooden molds of different sizes. The blocks were then carried up the ramps and placed to construct the pyramid. It would have been cumbersome and unnecessary to cast these small blocks in place.

Relief drawings on the sandstone cliffs near the Sinai mines show Sekhemkhet smiting the local desert people in order to protect mineral deposits. Rothenberg’s expedition examined tool marks and graffiti on cavern walls, enabling a distinction between early and late mining operations. Whereas Middle and New Kingdom dynasties used pointed metal tools, in earlier times mine shafts were produced with pointed flint tools. Rothenberg observed that the mines were most heavily exploited by the end of the Fourth Dynasty. In other words, the mines were heavily exploited by the time the major pyramids were built [76].

Sandstone masses were removed from the mines by producing a series of holes. This stone was then crushed into sand with harder rocks to free the mafkat nodules.The mafkat itself was most likely transported back to Egypt to be crushed for the cement.

A pyramid located at Zawiet el-Aryan, not far from Giza, is known as the Layer Pyramid and belongs to the first phases of Egyptian architecture. It has not been attributed adequately. Pharaoh Kha-ba’s name is found in the nearby cemetery, making him the most likely builder (Fig. 63). The Layer Pyramid was poorly constructed and is in a state of ruin. The use of small limestone blocks here still prevails, but they have become somewhat larger. The block quality is inferior and is believed to originate from a quarry to the south. This quarry may well be the origin of the aggregates used to produce blocks for the pyramid. No chemical analysis has been made of these blocks, but their inferior quality could be the result of several factors.

Figure 63: Depiction of projected outline of Kha-ba's pyramid, which was never completed, rises over ruins (J.P. Lauer).

A mining or general work slowdown or the use of inferior minerals are possibilities. If the king was elderly when crowned or in poor health, mining, a difficult and very time consuming operation, might have been cut back and the cons- truction work completed as well as possible with the least amount of cement before his death. If the cement were used sparingly, the resulting blocks would not be well adhered. If these were poor agricultural years, vegetable products (plant ashes) for the cement might have been less abundant. Another possibility is that the noncarbonate parts of the limestone did not react. This occurs if the clay in the limestone is of a type called illite by geologists.

It is also possible that the cement used did nor harden fast enough to produce good quality blocks beyond a certain size. The blocks did not crack to pieces as the larger size present in this pyramid, and they perhaps seemed adequate during construction. Close observation may have revealed tiny cracks or a poor finish, prompting the Heliopolitan specialists to continue experimenting with the formula.

The objective for Third Dynasty builders was to achieve more rapid setting, yielding larger blocks of better quality. Building with larger units has definite advantages. The architects no doubt realized that large blocks, being difficult to move, provided more protection for the burial chambers. Large units are less likely to be exploited at a later date, and transporting stones is a lot of work that can be eliminated provided the blocks can be cast directly in place. In other words, the larger the building units, the less work involved.

Three other structures built far from Memphis are tentatively grouped into the Third Dynasty. Generally, these show no architectural advance over Pharaoh Zoser’s pyramid. These pyramids are small and far inferior except for larger blocks. Third Dynasty pyramids were designed as stepped structures with subterranean tombs. Structural designs varied in the different pyramids as architects experimented with engineering possibilities.

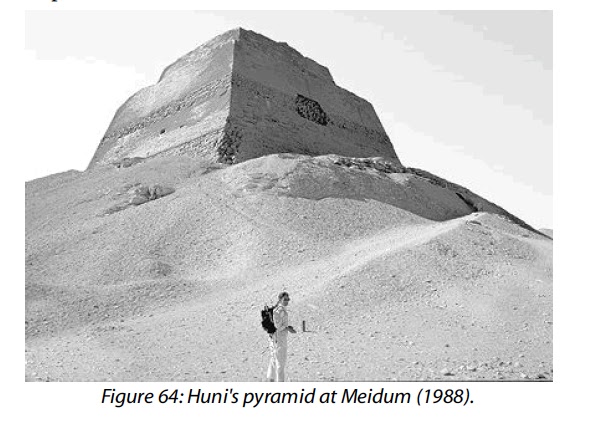

The last Third Dynasty king was Huni, also the last to build a step pyramid (Fig. 64). His structure is usually discussed in connection with Fourth Dynasty pyramids because of its controversial history. It seems that Sneferu, the first king of the Fourth Dynasty performed an experiment on Huni’s pyramid. Huni’s large step pyramid had been beautifully constructed at Meidum, forty miles south of Mem- phis. It originally had seven tiers and stood ninety-two meters (304 feet) high. Some of its blocks weigh about 0.25 tons x (550 pounds).

Figure 64: Huni's pyramid at Meidum (1988).

When Sneferu was enthroned, he ordered his workmen to increase its height and add additional casing blocks from the base to the summit of Huni’s pyramid. This produced the first exquisite, geometrical pyramid. The design was hailed as a great innovation, the inspiration for subsequent pyramids. The newly transformed pyramid, with its smooth finish of casing blocks, reflected brilliant streams of gleaming sunlight and won Sneferu the reputation of solar innovator. Sneferu ushered in the era we call the Pyramid Age.

At some point in history Huni’s elegant superstructure or Sneferu’s mystical architectural form underwent a sudden, cataclysmic demise. Much of its outer masonry crashed to the ground in one tumultuous earth-shaking moment. A huge mound of stone debris resulted. It still surrounds the monument. The site attracts a great deal of attention, with the causes of the incident becoming one of the puzzles of Egyptology.

The generally held theory is that, at an unknown date, key support blocks shifted out of place or were removed. If the latter, the most likely culprit would have been Ramses II, who was notorious for pillaging blocks from pyramids for his own monuments. Other theories accounting for the cataclysm are that the pyramid was disturbed by an earthquake or that there were incompatibilities between the original and the radical new design. Any of these possibilities might have caused a chain reaction, setting off the enormous avalanche that tore away most of the outer masonry [77]. Now, when viewed from afar, the remains have the surreal appearance of a fabulous high tower rising from the midst of an enormous mound.

Sneferu was the most industrious builder in Egyptian history. On the Libyan plateau, six miles south of Saqqara, at Dashur,he constructed two gigantic pyramids.They dominate the skyline even today. He appropriately named the first the Southern Shining Pyramid, and the second, to the north, the Shining Pyramid. Today they are known as the Bent Pyramid (also Rhomboidal, Blunted, and False Pyramid) and the Red Pyramid, respectively (Fig. 65). Together they incorporate more stone than the Great Pyramid. Sneferu’s workmen produced the monuments during the king’s twenty-four year reign, and we have already considered the logistical problems that this creates for engineers.

Figures 65: Sneferu's Bent Pyramid and Red Pyramid (1988). Figure 66: A stele of Sneferu was engraved on a cliff face in the Sinai.

In addition, the Palermo Stone records that Sneferu built temples throughout Egypt. He is also believed to have constructed the first Valley temples and causeways, as well as the small, subsidiary pyramids found south of parent structures. These types of masonry works adorned his own construction and were also believed to have been added by him to Huni’s complex. Sneferu far exceeded other prolific builders of Egyptian history.

The Palermo Stone records that he sent to Lebanon for cedar. He launched a fleet of forty large ships to retrieve enormous beams of cedar at the Lebanon coast, the same sort of mission carried out since early times. We have already considered how this historical event connects with the preparation of molds and containers for pyramid construction. Also relevant is that Sneferu’s name is found in the Sinai in large reliefs in the cliffs. As would be expected, he exploited the mines on an enormous scale. The Sinai mines exploited by him were known as Sneferu’s mines for 1,000 years (Fig. 66).

Sneferu’s Bent Pyramid was the first of the truly colossal superstructures. It is well preserved with a tip that is still pointed, and a great many of its casing blocks remain intact. Some of the casing blocks on the lower part of the pyramid are reported to be five feet high, a sure sign of cas- ting on the spot, whereas some of the smaller masonry fits together fairly roughly, suggesting the use of precast stone bricks. The heights of blocks range from small to large, providing for stability.

The modern name of Bent Pyramid was inspired by the angle of its slope, which suddenly diminishes on the upper half of the pyramid. Its shape makes it unique among pyramids. It is assumed that the architect radically altered the angle in an attempt to reduce the tremendous amount of stress on the corbeled walls of inner chambers, which, it is believed were already beginning to crack during construction. Yet, there could be another explanation.

For an unknown reason Sneferu went on to build the even larger Red Pyramid, so called because of the pink tint of its stones. Here the blocks are big, with each one cast directly in place. Cumulative alchemical and engineering developments afforded superior strength and design over all previous pyramids. The burial chamber, traditionally under- ground, was incorporated into the pyramid itself. The heights of the blocks vary from 0.5 meters (1.64 feet) to 1.4 meters (4.6 feet). The Red Pyramid stands 103.36 meters (113 yards) high, and has a square base of 220 x 220 meters (240 x 240 yards). Its dimensions approach those of the Great Pyramid to follow. Both pyramids were until 1995 in a restricted military entry zone, so I have not examined them personally.

Figure 67: Prince Rahotep and his wife Nefret. Fourth Dynasty. Cairo Museum (1988).

Painted limestone statutes of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret, the former a son of Sneferu, were found in the cemetery around Huni’s pyramid at Meidum (Fig. 67). The paint used is a fine alchemical product that maintains its fresh color today. The inlaid eyes are truly exquisite, as would be expected of agglomerated stone. Eyelids are made of copper, the whites of the eye are quartz, and the corneas are rock crystal. The material composing the irises is of uncertain composition, thought perhaps to be a type of resin. The Fourth Dynasty produced the most remarkable statuary.

Another son of Sneferu was Khnum-Khufu (Kheops or Cheops), who built the Great Pyramid (Fig. 68). His full name shows his reverence for Khnum. Although today it is called the Great Pyramid, Khufu named his monument The Pyramid which is the Place of the Sunrise and Sunset. The name, inspired by Heliopolitan mythology depicted the pyramid as the throne of the Sun god Ra during his daily course across the heavens.

Figure 68: Cross section of the Great Pyramid.

Khufu and his pyramid were richly endowed with a royal estate, which had been maintained for thousands of years. During those years a line of priests assigned to Khufu faithfully maintained temples and property and ritually prepared offerings for the deceased god-king. Altars were covered over with offerings of flowers, incense, and food. Monuments that make reference to these priests date to several historical periods spanning thousands of years. They indicate that the tradition was not broken until Ptolemaic times.

This same tradition was upheld by priests of Khufu’s father, Sneferu, and also those of his son, Khafra (Khefren or Chephren). Like his father, Khufu sponsored numerous building projects. His name appears on monuments throughout Egypt. He excavated for minerals in the Arabian Desert, Nubia, and the Sinai, where he was depicted on the cliffs protecting the mines.

Much of the complex belonging to the Great Pyramid has been destroyed. Only the foundations of the enclosure walls and the mortuary temple remain. The great causeway that Herodotus remarked almost equaled the pyramid in size was practically intact until 100 years ago. Today many large blocks remain to provide an idea of its original size and solidity. Other portions of the complex, such as the Valley Temple, are yet to be excavated. The cemetery surrounding the Great Pyramid is the most extensive, with large, impressive mastabas.

The seventh or eighth in chronology, the Great Pyramid is the largest and represents the peak in engineering design. Never again would Egypt build on this scale. Because of its masterful construction, this monument is the most celebrated of all time. It is little wonder that modern engineers wince at the thought of duplicating this monument, even with the best equipment. The base is 232 meters (253.7 yards) per side and the area of the base is 5.30 hectares (13 acres). Through careful observation of the stars, the Great Pyramid was oriented more accurately than any other; it is off only one-tenth of a degree of present-day true north. Its original height is estimated to have soared to 147 meters (481 feet). Today it is about 138 meters (450 feet) high with its capstone and some tiers missing. Its volume is 2,562,576 cubic meters (90,496,027 cubic feet). It contains approximately 2.6 million building blocks and has an overall weight of approximately 6.5 million tons.

It is difficult to appreciate the enormous size of the Great Pyramid by reading statistics. Perhaps a better illustration is this: if all of its blocks were cut into pieces one-foot square and laid end to end, they would reach two-thirds of the way around the world at the equator. Notwithstanding all of the problems of pyramid construction already raised, if the blocks of the Great Pyramid were carved and their carving waste taken into account, the total weight of the stone used would have been close to 15 million tons-placing an enormous burden on the accepted theory.

The carving and hoisting theory indeed raises questions that have been insufficiently answered. In October 1991, during the shooting of the TV production “ This Old Pyramid ” by NOVA with M. Lehner, aired on the American PBS network, I witnessed the weaknesses of the traditional theories. The pictures I took there (Fig. 69-74) illustrate the difficulty of the task. Using stone and copper tools, how did workers manage to make the pyramid faces absolutely flat?

Figure 69: NOVA's mini pyramid (1991); Khufu's (Kheops or Cheops) pyramid in background.

Egyptologist can claim that the problems have been resolved. Theories of construction are many and continue to be invented.All are based on carving and hoisting natural stone, and none solves the irreconcilable problems. Only the agglomerated stone theory instantly solves all of the logistical

and other problems.

What direct evidence of molding is to be found in the Great Pyramid? The casing blocks are clearly the product of stone casting. As mentioned, most were stripped for cons- truction in medieval Cairo after an earthquake destroyed the city in AD 1301. Those that survive are at ground level, buried beneath the sand in 1301. Joints between the casing blocks are barely detectable, fitting as closely as 0.002 inch according to Petrie’s measurements. The casing blocks are smooth and of such fine quality that they have frequently been mistaken for light-gray granite. The English scholar John Greaves (1602- 1652) thought, at first sight, that they were marble.

Figure 75: Three possible positions for casting casing stones.

In 1982 the German Egyptologists Rainer Stadelmann and Hourig Stadelmann-Sourozian discovered that the inscriptions on the casing blocks of the Red Pyramid of Sneferu were always on the bottom [78]. This applies to the Great Pyramid as well and could indicate that the casing blocks were cast in an inverted position (method B or method C) against neighboring blocks. Once they hardened and were demolded, they were turned upside down and positioned. To find inscriptions consistently on the bottom is good evidence of the method by which they were made. Had the casing blocks been carved, inscriptions would be found on various surfaces.

Positioning the casing blocks was the most difficult and time-consuming part of building a tier. I still do not know whether the casing blocks were inverted and set while the rest of the tier was built from the inside and whether the packing blocks were added between the core masonry and the casing blocks to complete a tier.

The ascending passageway leading to the Grand Gal- lery had been plugged with three enormous granite blocks each 1.20 meters (3.9 feet) thick, 1.05 meters (3.4 feet) wide, and totaling 4.34 meters (14.3 feet) long. Edwards wrote [79]: “ The three plugs which still remain in position at the lower end of the Ascending Corridor are about one inch wider than its mouth and, consequently, could not have been introduced from the Descending Corridor ”. Since the plugging should have occurred after the funeral ceremony, Edwards continues, “ No alternative remained, therefore, but to store the plugs somewhere in the pyramid while it was under construction and to move them down the Ascending Corridor after the body had been put in the burial chamber ”. Egyptologists have hotly debated where the plugs had been stored but have offered no satisfactory answer. Although no analyses have been made of the granite plugs in any of the pyramids, I could suggest that these plugs in the Great Pyramid were agglomerated in the Grand Gallery and later slid into position. Yet, I do not have any proof on that matter.

Evidence of molding appears in the ascending passageway. The blocks in this passageway are alternately set in either an inclined or vertical position. Although the inclined blocks have no structural function, the blocks set vertically support the passageway itself. There are large monolithic gates, consisting of two walls and a ceiling, made in a reverse-U shape. The evidence that these gates were molded are the mortises, later filled with cement, in the floor beneath them. Poles were inserted in these mortises to support the part of the mold needed to form the ceilings of the gates.

Figure 76: Mortises and vertical grooves in the Grand Gallery (I.E.S. Edwards).

In addition, the sample provided by Lauer was from the wall of the Ascending Passageway. I have already described the sophisticated geopolymeric binder I detected, the stress bubbles, organic fibers, and wood-grain impressions exhibited in the sample.

The Grand Gallery is the most spectacular masonry feature of the interior of any pyramid. It measures 47.5meters (156feet) long, 8.5meters (28 feet) high, and 2.1 meters (7 feet) wide at the floor level. Its walls are corbeled. One of Jomard’s comments about the Great Pyramid was [80]: “ Everything is mysterious about the construction of this monument. The oblique, horizontal and bent passageways, different in dimensions, the narrow shaft, the twenty-five mortises dug in the banks of the Grand Gallery... ” Jomard was referring to the mortises carefully plotted on the drawings made by Cecile for Description de l’Egypte (Fig. 76).

Jomard did not notice that each square mortise in the floor corresponds with a vertical groove in the walls (Fig. 77). The two French architects, Gilles Dormion and Jean-Patrice Goidin, who drilled a hole in the wall of the Queen’s Chamber in 1987 in their search for hidden chambers, proposed that the purpose of the mortises was to stabilize poles that supported a wooden floor leading to a hidden passageway, which they failed to find [81]. Any hidden chambers which may be found would add to the complexity of building the pyramid according to the accepted theory.

Probably, these mortises and grooves were necessary for casting blocks. To produce a rectangular block, the mold must be oriented horizontally because, like water, a slurry will seek its own horizontal level when poured. If a block were cast on an incline, a misshapen block would result (Fig. 77). The blocks for the corbeled gallery were cast, therefore, in the horizontal position. The support mechanism was a wooden plank secured to the appropriate groove in the wall. The top of each groove is horizontal to the next mortise up. The plank was weighted, perhaps with a sandbag. Removing the weight disengaged the wooden structure so the finished block could be lowered and pushed into position.

Figure 77: Blocks were cast horizontally (A), and after setting, they were moved into the inclined position (B) to build the walls of the Grand Gallery.

Though they found no chambers or enormous holes, that core blocks are lighter than the bedrock was recognized in 1974 by the SRI International team. SRI International found the density of the blocks of Khafra’s pyramid twenty percent lighter than the bedrock [82]. Lighter density is a consequence of agglomeration. Cast and rammed blocks are always twenty to twenty-five percent lighter than natural rock.

The Grand Gallery leads up to the so-called King’s Chamber, deep in the interior and about two-thirds of the way up the pyramid. The blocks composing the flat roof of the King’s Chamber are impressive, among the largest in the entire structure. The roof consists of nine monolithic slabs weighing about fifty tons each, totaling about 450 tons. The floors and walls of the King’s Chamber are made similarly of finely jointed red granite that appears to be polished.

If one considers size, design and construction time limits, it becomes clear that if the Great Pyramids were dependent on primitive methods of carving and hoisting, they would not exist. In the Great Pyramid, hundreds of blocks that make up the core masonry weigh twenty tons and more and are found at the level of the Grand Gallery and higher. We have examined how the first pyramids were constructed of blocks weighing only a few pounds apiece. As engineering methods and design improved, casting stone directly in place in larger and larger units resulted in, to a civilization in the final phases of the Stone Age, monuments that stun modern observers, monuments that cannot be sufficiently explained today by experts or effectively duplicated within the appropriate amount of time by carving and hoisting natural stone. Now, we will examine the reason why, like the extinction of a mighty species, pyramid building in the sands of Egypt ceased.

--------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment