BOOK: THE PYRAMIDS AN ENIGMA SOLVED

Prof. Joseph Davidovits

Chapter 9

The Birth of Masonry

The role of the historian is to explain why events occur as they do. Many important facets of history have eluded historians as a result of lost knowledge about the alchemical stonemaking technology. Now that the old science is recovered, one is called to re-examine several is- sues. New light is shed on the developments that led to the construction of the first pyramid. One can recognize reasons for the rise and decline of pyramid building. These have been improperly understood as have critical periods of instability and decline in the Egyptian civilization. Then there is the question of how such an important technology could have been lost. If the old science really did exist, there must be some historical traces. An exploration of these issues sheds new light on many aspects of history. The historical remnants provide additional, powerful proof and significantly deepen our understanding.

The oldest known remains of high-quality cement are found in the ruins of Jericho in the Jordan valley. They date from 9,000 years ago. We know that white lime vessels, based on the synthesis of zeolites, were produced in Tel-Ramad, Syria, 8,000 years ago. Mortar from this era has also survived from Catal Hujuk, Turkey. The existence of these ancient products suggests that the earliest stonemaking technology migrated into Egypt.

Settlers attracted by the fertile valley arrived with various animals, plants, traditions, skills, materials, and processes. Hard stone vessels first appeared in pre-dynastic Egypt at about 3800 BC. Later, approximately 30,000 hard stone vessels were placed in the first pyramid, the Third Dynasty Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Many of the vessels were handed down from ancestry.

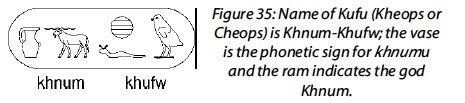

Stone vessels were sacred funerary objects, probably offering vessels. Stone vessels symbolized the god Khnum, the Divine Potter, also depicted with the head of a flat-horn ram. When hieroglyphic writing was invented, Khnum was represented by the stone vase symbol (sign W9 in Gardiner’s list). Although unrecognized by Egyptologists, because they have been unaware of its existence, alchemical stonemaking was attributed to Khnum (Fig. 35). Egyptology classifies Khnum as a significant early god. But the profound influence of Khnum’s religious tradition is vastly underrated.

Figure 35: Name of Kufu (Kheops or Cheops) is Khnum-Khufw; the vase is the phonetic sign for khnumu and the ram indicates the god Khnum.

Khnum is one of the most ancient prehistoric Egyptian gods. Since remote times he possessed many attributes. Like all other Egyptian gods, he was identified with the Sun god, but notably he was regarded as one of the creators of the universe. As the Divine Potter, he was the ultimate technocrat. Khnum was depicted as the Nile god of the annual floods whose outstretched hands caused the waters to increase. The Nile floods were believed to originate from a sacred cavern beneath the island of Abu (first town), now known as Elephantine, the major center of Khnum worship (Fig. 36). Over the eons the annual inundation gradually converted a narrow strip of about 600 miles of coast into rich land, unparalleled for farming.

Figure 36: Detail of bas-relief from temple Khnum at Elephantine (Description de l'Egypte). God Khnum (right) welcomes Pharaoh (center).

Khnum’s influence grew steadily in early epochs, but diminished after the Twelfth Dynasty and made a resurgence in the Eighteenth Dynasty. Khnum was usually depicted in human form with the head of a flat-horned ram. He was also depicted with four ram heads on a human body, which according to Egyptologist Karl H. Brugsh represented fire, air, earth, and water. The flat-horned ram was not native to Egypt, suggesting that the technology for making hard stone vessels was brought to Egypt by migratory shepherds whose national symbol was the flat-horned ram.

During antiquity it was customary to depict profes- sion or tribal identity symbolically. In the ancient custom, men of truly great accomplishment were deified, and great principles of nature and science were attributed reverence and honor through divine personification. Other symbols of the shepherd were not personified but became part of the ceremonial vestments of the god king. Throughout pharaonic times the king’s royal garb always included the crook and incense-gum collecting flail of the shepherd. The symbols were clearly associated with divine political influence.

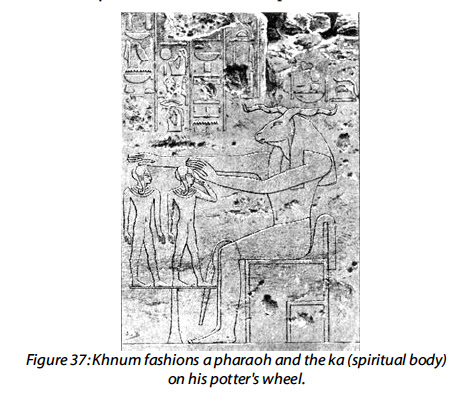

Figure 37: Khnum fashions a pharaoh and the ka (spiritual body) on his potter's wheel.

The most ancient mythology of the Old Kingdom recounts that the Divine Potter created other gods, divine kings, and mortals on his potter’s plate. Khnum used different materials depending on whether the being created was di- vine or mortal. Divine beings were depicted with materials indicative of the eternal realm. Gods were often depicted in gold with hair of lapis lazuli. The funerary statue of the pharaoh, representing his ka (eternal body), was made of stone. The divine spirit was incarnated in the eternal material of stone (Fig.37).

The mortal man was made of the reddish-brown mud of the Nile River, and man was always depicted in reddish brown on bas-reliefs. The perishable mortal body was destroyed by aging and death. Only with an offering of Khnum’s sacred alchemical product, the natron salt, could immortality be imparted at death. If a man was sinful, he knew that his body would be thrown into the river. The sinful would not attain immortality through the seventy-day mummification ritual using natron.

Natron never lost its sacred value. In the Talmud, na- tron symbolized the Torah (the Law). In Leviticus 2:13 of the Bible, natron was the salt of the covenant between God and the people:

“ And every oblation of thy meat offering shalt thou season with salt; neither shalt thou suffer the salt of the covenant of thy God to be lacking from thy meat offering: with all thine offerings thou shalt offer salt. ”

The salt mentioned in this verse is not sodium chloride or potassium nitrate, but natron. Proof of this can be derived from information provided in Proverbs 25:20:

“ As he that taketh away a garment in cold weather, and as vinegar upon nitre [salt], so is he that singeth songs to an heavy heart. ”

An adverse effect is implied in the verse. If one places vinegar on natron (sodium carbonate), the natron disintegrates, leaving a sodium acetate solution. If vinegar is put onto potassium nitrate or sodium chloride there is no disintegration.

The Genesis authors in the Bible described Creation within the framework of their knowledge, revered information handed down from remote ancestry. Assyriology has been studied widely in relation to the Old Testament, whereas the Egyptian influence has been mostly disregarded.

The remotely ancient tradition of Khnum is historically outstanding, for it has prevailed in some form throughout the written history of mankind. Thousands of years after the pyramids were built, Khnum was worshipped by the Gnostics, a semi-Christian sect. What is not widely recognized is that the Bible still preserves the age-old religious tradition characteristic of Khnum.A passage from an Egyptian creation legend by Khnum follows:

“ The mud of the Nile, heated to excess by the Sun, fermented and generated, without seeds, the races of men and animals. ”

Passages of the Bible leave no doubt about the belief in the concept of the Divine Potter. Genesis 2:7 mentions the material used to make man, the same type of substance used by Khnum:

“ And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life: and man became a living soul. ”

The Hebrew verb used in the verse to signify deity is ysr, the root of yoser; which means potter. Further, the tradi- tion can be shown by Job 33:6, where Elihu reminds his elders that he is entitled to speak in their presence:

“ I am your equal as far as God is concerned; I, too, have been 150 pinched off from clay ”

The tradition of the Divine Potter can be further observed in Isaiah 29:16:

“ What perversity is this! Is the potter no better than the clay? Can something that was made say of its maker, “ He did not make me ”? Or a pot say of the potter,“ He is a fool ”? ”

and Isaiah 64:7:

“ And yet, Yahweh, you are our Father: we the clay, you the potter, we are all the work of your hand. ”

The hard stone vessels of Khnum exhibit characteristic features of man-made reconstituted stone. To explain the vessels, Egyptologists assert that a vesselmaker spent perhaps as much as his entire life making only one vessel. But the design features of some of the vessels indicate that time was not the critical factor. Very hard stone materials, basalt, metamorphic schist, and diorite were being used to make the vessels at about the prehistoric epoch when copper was first smelted. The smooth surfaces, absence of tool marks, the vases with long, narrow necks and wide, rounded bellies and interiors and exteriors that perfectly correspond -features unexplainable by any known tooling method- are characteristic of a molded or modeled material. The methods afforded by geopolymerization, a slurry, or rock aggregates, poured into a mold or a pliable mixture fashioned on a potter’s wheel, are truly the only viable means by which to explain the features of these otherwise enigmatic vases. The following are remarks made by Kurt Lange after he studied fragments of stone vessels that he found in the sand and talus near the Step Pyramid at Saqqara (Fig. 38) [44a]:

“ This noble and translucid material is of exceptional hardness.... They are made of a perfectly homogeneous material, dense, polished, and glossy.... At once robust and fra- gile, of unequaled finesse and elegance of shape, they are of supreme perfection. The internal face is covered with a microscopic network of tiny grooves so regular that only an ultramodern potter’s wheel of precision could have produced them. To see the grooves one needs a magnifying glass and good lighting.... Obviously, the equipment used must have been some kind of potter’s wheel. But how could such a hard material be worked?... the plates on which earthenware pots were made with such regularity of form had only just been invented, and it is hard to believe that it was this tool, doubtless still extremely primitive, which was used in the fabrication of the hardest and most perfect bowls ever made. ”

Figure 38: Stone vessels found in the Step Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara by J.P. Lauer and Drioton

Egyptologists assume that the hard stone vessels were drilled with a type of tool often displayed in different tomb representations. This tool is a straight shaft with an inclined and tapered top handle. Two stones or bags of sand were fastened just under the handle (Fig. 39 a, b). Yet no drills of this type have ever been found. Rather, archaeological remains feature bow-drilling tools, a technology always depicted for drilling all kind of materials. According to Denys Stock [44b] the rate of drilling granite with the tool recommended by Egyptology is in the order of 60-75 times slower than drilling limestone by a copper tubular drill driven by a bow. I am therefore inclined to consider that the tool displayed in the tomb representations has a different purpose. For example, a bas-relief from the Sixth Dynasty tomb of Merah, at Saqqara, is interpreted by Egyptologists to depict workmen drilling out stone vessels (Fig. 39a). In 1982, I presented a different interpretation at the 22nd Symposium of Archaeometry, held at the University of Bradford, in Bradford, United Kingdom [45]. The vessels shown were made of Egyptian alabaster, a calcium carbonate stone.Alabaster vases made as shown were not carved or agglomerated. It is obvious the vase makers are not drilling. Rather they are squeezing a liquid, stored in a sewn animal skin or a bladder, through a tube. I suggested that they were drilling with the means of bio-tooling, that is, using an acidic liquid such as vinegar, citric or oxalic acid, or a combination of acidic liquids extracted from plants, to act upon the alabaster (calcium carbonate). It is well known that acidic plant saps dissolve calcium carbonate very easily. I have measured the efficiency of using acidic liquids of the type just mentioned on Egyptian alabaster in my laboratory. The conclusion of our scientific paper reads as follow:

“ An experiment of interest was to compare the bio-tooling technique with the shaping of a hole (in local limestone) using steel tool and the quartz sand technique recommended by archaeologists.The test was run for 15 minutes and the drilled volume was measured for each technique: for steel tool 12 ml, quartz sand 8.5 ml, bio-tooling 9.5 ml. (bio-tooling mix contains vinegar,citrus sap and oxalic sap).The hole resulting from sand abrasion has rough walls, whereas bio-tooling gives a smooth finish. ”

The bio-tooling technology with acidic saps is not feasible when dealing with hard stones. It only works for calcium carbonate based stone, not for granite, basalt, hard schist and the like.

Another product was lime, CaO, acquired by calcining limestone or dolomite. Two of the earliest products of humankind are lime and bread. Yet, the lime supply for stonemaking in Egypt may have been a by-product of breadmaking. The collected wood and plant ashes may contain between 50 and 75 per cent by weight of lime CaO. The Nile valley was blessed with produce of all kinds, and some plants and trees would produce more or less lime CaO in their ashes. For bread, the main crops were winter and summer wheat and six-row barley. After agriculture was introduced in the Faiyum region during neolithic times, the lifestyle of the inhabitants of the Nile Valley gradually transformed from hunter-gatherer to farmer. Bread consumption increased over the epochs with expanded irri- gation. Late records indicate that the Greeks dubbed the Egyptians artophagoi, the bread-eaters.

With the pharaohs involved in increasing agricultural yield, one can appreciate the precarious position of the high priests responsible for oracles and interpreting the pharaohs’ dreams. The size of the pharaohs’ monuments may well have depended on the predictability of the Nile. Enormous quantities of lime-ash from breadmaking in hearths, would automatically have been available and collected for stone- making during plenteous years. Soda (natron) ritually added to bread dough to make unleavened bread during remote antiquity, would have placed all of the required elements (lime, natron, and water) in close proximity for the invention of one of the primary ingredients of stone making, caustic soda.

The Nile yielded sacred water for the process. Egyptian cosmogony asserted that the Nile water was the original abode of the gods from which sprang the forces of light and darkness. The Egyptian name for the Nile was Hapu, and the Nile god Hapu was identified with the cosmogonic gods. Hapu took the form of Khnum during the inundation, when an annual solemn, festival was celebrated to rejoice the rise of the waters.

Many types of rock aggregates, considered by the Egyptians to be withered or injured rocks, were available. Examples are flint, slate, steatite, diorite, alabaster, quartzite, limestone, dolomite, granite, basalt, and sandstone. Precious gems, such as diamond, ruby, and sapphire, were unknown. Semiprecious varieties acquired by mining or trade included lapis lazuli, amethyst, carnelian, red jasper, peridot, amazonite, garnet, quartz, serpentine, breccia, agate, calcite, chalcedony, and feldspar.

Table II. The Mafkat Minerals

“ I found that it was difficult to determine the right color when the desert is hot in the summer The hills burn... and the colors fluctuate... during the severe summer season the color is not right. ”

Chrysocolla dehydrates in the hot desert sun, becoming whitish on the surface. Heating a sample with a flame would also have enabled a distinction because chrysocolla causes a flame to turn green. Nile silt was probably an ingredient of the earliest vessels. Silt was the traditional material for Khnum’s mortal processes, and perhaps a union between the divine and mortal was symbolized through stonemaking.

Another substance was not vital to the chemistry but may have been added because it symbolized the highest spiritual essence. The product was gold, the metal of the Sun. During my analyses, I found flecks of gold dust in Lauer’s sample from the Great Pyramid. It is possible that the gold did not occur naturally and was instead ritually added. Di- vine eternal qualities were attributed to gold. In addition to its beauty and association with the Sun god, gold does not rust or tarnish and can be worked indefinitely without becoming brittle or damaged. Even though gold was probably always an item of exchange, anciently its value was purely sacred.A monetary value gradually manifested.Some experts believe that the Egyptians never minted state gold coins until the Greek occupation or after 332 BC.

The practices of the first vesselmakers are lost in prehistory. A standard system of weights and measures was not adopted by 3800 BC. We can, therefore, only conjecture about a recipe for making a stone vessel of that period:

THE ETERNAL VESSEL of Khnum

- 1 heqat natron + 2 heqat wood ash

- 2 hin Nile water

- 2 heqat powder of mafkat + 3 heqat Nile silt + 5 heqat

- eternal rock particles

- Ceremonial quantity of gold dust

Combine the sacred natron with ash powder collected from the hearth and blend them in a ceramic bowl with blessed water to form the caustic substance. Obtain mafkat which turns white on the surface during summer and which produces a green color of fire when you burn it. Powder the mafkat by crushing it with hard rocks and add it to the caustic substance. When the mafkat has been consumed, add fine silt such as Khnum uses to make perishable creatures.Recite prayers every day until the liquid has the consistency of honey, then add the injured, eternal aggregates (the limbs of Neter [God]), and the golden particles (the spirit of Neter), to incarnate His Di- vine Presence.

Protect your hands with oil and knead the material. Then fashion the vessel on your turning plates. Tear strips of linen and coat them with bitumen. Wind the strips around the outside of the vessel. Line the inside and carefully pack it. Allow the vessel to remain overnight. It will gain strength.When the vessel is strong, unwind the linen. Cover the vessel loosely with a linen cloth so that it can breathe. Remove the cloth when the vessel attains eternal life. Rejoice that Khnum’s living vessel may endure forever!

Although the ritual is speculative, the chemistry is based on reactions that work very well in our laboratory. An analysis of stone pottery may prove that the early binders were far more sophisticated. A process involving turquoise and allowing objects to harden in air-tight molds was introduced at about 3000 BC and is described in Appendix 1. Methods used to make vases with narrow necks and rounded bellies were innovated for making glass vases in the Eighteenth Dynasty at about 1350 BC.

From primitive beginnings, Khnum’s alchemical stonemaking technology advanced beyond pottery to produce the world’s most impressive architecture. The earliest burial places were pits, where funerary gifts were placed for use in the afterlife. Buried bodies were naturally preserved in the warm, dry sand of the desert necropolises. Mastabas represent the next phase of tomb construction. These are rectangular mud-brick structures, named mastabas from the Arabic word for bench used to describe their shape.

Stone material began to appear in the mastabas erected at Abydos and Saqqara during the Archaic period. These tombs have been badly plundered and only enough material remains to establish a tenuous history of this period. The remains suggest a constant evolution of mastaba design and an increased magnificence of furnishings. The early royal mastabas of the First Dynasty consisted of a large covered underground chamber surrounded at ground level by a wall. As the dynasty progressed, the tombs acquired additional storerooms and an access stairway. Large wooden beams and linings were incorporated into the tombs of the pharaohs. Sealed in the tombs were funerary offerings of food, precious articles of copper and gold, and various commemorative items. The tombs also included a vast array of alchemically made vessels in various beautiful shapes and hard stone materials.

An artifact from a First Dynasty cenotaph indicates that the precious mafkat deposits were jealously guarded. An ivory label of Den, the fifth king of the First Dynasty, depicts him symbolically smiting a bedouin in the Sinai.

A dramatic architectural advance appeared by the end of the Second Dynasty. Adjacent to the mastabas the king built a large enclosure. The well preserved Palace of Eternity erected by Khasekhemwy, the last king of the Second Dynasty in Abydos, consists of imposing crude brick walls, 10-12 meters high and more than 700 meters periphery (Fig. 40).

Figure 40: Khasekhemwy's enclosure made of crude bricks, Abydos.

Until recently, local tradition assimilated this construction to the grain storehouses of the biblical patriarch Joseph, or to military fortifications. In fact, Khasekhemwy’s Palace of Eternity was a replica of the enclosure wall of his secular palace. The enormous walls are crenellated, composed of alternating projections and recesses.A great number of their crude silt bricks are in excellent conditions, with little or no sign of erosion, after 5000 years. The crude bricks were overlaid with a decorative coating of white gesso, or white plaster. Khasekhemwy is the first of the great builders in Egyptian history.

The next major technological innovation, based on Khasekhemwy’s superstructure, would revolutionize mortuary construction and have dramatic impact on the course of history,

--------------------

Chapter 10

The Invention of Stone Buildings

Khasekhemwy left no male heir to the throne, and the Third Dynasty pharaoh first to rule was Zanakht. He was followed by Neterikhet (Zoser). Pharaoh Zoser’s architect, Imhotep, was responsible for the construction of the first pyramid. Before discussing this accomplishment, we will review what little relevant information has survived about this intriguing historical personality. Imhotep left an unforgettable legacy. Historically, the lives of few men are celebrated for 3,000 years, but Imhotep was renowned from the height of his achievements, at about 2700 BC, into the Greco-Roman period. Imhotep was so highly honored as a physician and sage that he came to be counted among the gods. He was deified in Egypt 2,000 years after his death, when he was appropriated by the Greeks, who called him Imuthes and identified him with the god Asclepius, son of Apollo, their great sage and legendary discoverer of medicine.

Figure 41: Statue of Imhotep.

Imhotep wrote the earliest “ wisdom literature ”, venerated maxim, which regrettably has not survived, and Egypt considered him as the greatest of scribes. This presiding genius of King Zoser’s reign was the first great national hero of Egypt. During King Zoser’s reign, Imhotep was the second most eminent man in Egypt, and this is registered in stone (Fig. 41). On the base of a statue of King Zoser, excavated at the Step Pyramid, the name and titles of Imhotep are listed in an equal place of honor as those of the king. Imhotep had many titles, Chancellor of the King of Lower Egypt, the First after the King of Upper Egypt, Administrator of the Great Palace, Physician, Hereditary Noble, High Priest of Anu (On or Heliopolis), Chief Architect for Pharaoh Zoser, and, interestingly, Sculptor, and Maker of Stone Vessels.

The titles confirm the records of the Greco-Egyptian historian Manetho on Imhotep, written in Greek 2,400 years later, during the early Ptolemaic era, in the third century BC [47]. Manetho was one of the last high priests of Heliopolis. Part of his text (reported by Sextus Julius Africanus) was translated in AD 340 by the ecclesiastic historian Eusebius to read, “ the inventor of the art of building with hewn stone ” . In fact, Eusebius’s translation is incorrect. The Greek words Manetho used, xeston lithon, do not mean hewn stone: they mean polished stone or scraped stone. The words describe stone with a smooth surface, a feature characteristic of fine, agglomerated stone [see the discussion in note 48]. These words were also used in the Greek texts of Herodotus (see the discussion in Chapter 12). It is impossible for translators accurately to translate texts while lacking vital technical knowledge. Similar errors of translation have been made throughout history, and more examples will be provided. For Manetho, Imhotep was “ the inventor of the art of building with agglomerated stone ”. This refers to the construction of the first pyramid (Fig. 42).

Figure 42: Step pyramid of Zoser was the world's first building made entirely of stone.

Imhotep was regarded as the son of a woman named Khradu’ankh and the god Ptah of Memphis. The title Hereditary Noble indicates aristocratic parentage. His career would have begun when he was a boy trained by a master scribe. With his parents among the elite, lessons would have begun around the age of twelve. Because priests were among the literate of Egypt, he may have received scribal training by entering the priesthood. His title, High Priest of Heliopolis, was traditionally attained on two conditions. A man either succeeded his father in the priesthood, or he was personally appointed to office by the king because of some great deed. The position of high priest was attained after extensive trai- ning in the arts and sciences-reading, writing, engineering, arithmetic, geometry, the measurement of space, the calculation of time by rising and setting stars, and astronomy. The Heliopolitan priests became guardians of the sacred knowledge, and their reputation for being the wise men of the country sustained even into the Late Period.

Their religious ideologies and sciences were heavily applied to the construction of tombs and other sacred archi- tecture. A magnificent solar temple oriented by the heavenly bodies was erected during the reign of Zoser to mark the most sacred place in Heliopolis. The city was the holy sanctuary of Egypt, the ground itself religiously symbolic. The site for Heliopolis had been chosen at a location in the apex of the Delta where the inundating Nile waters first began to recede. There the earth, fertilized by the arrival of silt and nurtured by the Sun, received the first renewed life of the agricultural year. This ground represented rebirth and Creation.

Located about twenty miles north of Memphis, the town is estimated to have measured 1,200 x 800 meters (3/4 mile x 1/4 mile). It became the capital of the thirteenth Lower Egyptian nome or district. No precise archaeological history of the city has been established. So it is unknown when ground was first broken for construction. The city is considered to have been founded during prehistory, and it had a very impressive life span. It flourished in the Pyramid Age and still remained an important center when Herodotus visited Egypt in the fifth century BC. Today, all of the temples and buildings of Heliopolis have vanished and the abandoned site has been incorporated into a suburb of eastern Cairo. Only a single standing obelisk, erected for a jubilee of Pharaoh Sesostris 1 (1971-1926 BC), remains amid empty fields.

When King Zoser was enthroned, he no doubt expected to be buried in a mud-brick mastaba with a superb Palace of Eternity similar to that of his predecessor Khasekhemwy. The site for his tomb was selected at Saqqara, south of Memphis. Design plans and calculations for orienting the monuments were being made. At this point, the subsequent history of the construction of all pyramids must be revised on the basis of my discoveries.

Khasekhemwy’s Palace of Eternity provides a key ar- chitectural design, which has been ignored by the archaeological community. Because the massive walls were made of crude bricks, formed in molds, it has always been stated that the brick sizes would be uniform from one layer to the other. The picture of Khasekhemwy’s enclosure wall and the sketch focusing on the bricks heights, reveal that this statement is entirely wrong (Fig. 43a,b).

Figure 43a: Enclosure of Khasekhemwy Palace of Eternity is made of crude bricks of different sizes. Figure 43b: Five sizes for crude bricks in Khasekhemwy's enclosure.

Khasekhemwy’s enclosure displays five different brick sizes. By measuring the height of 11 successive layers, I found that layer no.7 contains large crude bricks of size (I), layers no. 1, 4, 5, 11, medium high bricks of size (II), layers no. 3, 6, 10 medium bricks of size (III), layers no. 8, 9, medium bricks of size (IV) and layer no.2, the smallest size (V). In other words, the architect deliberately prepared 5 different molds for the manufacture of the crude clay bricks. In the previous Chapter 8 on the Proofs at Giza, I mentioned how the staggering block heights produce tremendous stability. This key architectural knowledge was continuously used in the construction of every major building erected since that time. It explains the height variations measured for Khufu Pyramid layers, displayed in Fig. 5.

Minerals were being excavated to produce stone and blue ceramics for lining interior walls and floors. King Zoser’s workmen inscribed a stele in the sandstone cliffs of the mi- nes of Wadi Maghara in the Sinai to commemorate the cons- truction of the monument. Some time before actual cons- truction got under way, Imhotep made an important discovery. Certain titles of this Chief Architect, Sculptor, and Maker of Stone Vessels profile prerequisite skills for building a monument with alchemically made stone. He would have applied himself to producing a mastaba which would last forever. Like the pride in a great nation, the pride intrinsic to a monument would be its longevity.

Khnum’s clergy apparently amalgamated its alchemical science with that of the Heliopolitan priests when stone was first made for use in architecture. Imhotep perhaps specialized in materials processing or alchemy. His aim may have been to strengthen the sun-dried Nile silt bricks used for mastabas and enclosures. Any attempts made by Imhotep or others to fire bricks made of silt from the Nil River would have been futile. The Nile silt contains the refractory element aluminum oxide, not the silico-aluminates, the components required for producing good, fired bricks at temperatures that they were capable of achieving. They would not even come close to the required temperatures of 1,300 to 1,500°C (2.400 to 2,700°F). Ordinary clay had been fired for pottery since pre-dynastic times by using fluxes to lower firing temperature, but this fired material was impractical for construction purposes.

Let us suppose that Imhotep discovered the properties of the yellow limestones located at Saqqara: a lime-sandstone and a clay-limestone (marl). These materials contain a mini- mum of 10%, sometimes up to 60% of aluminous clay, which is released in water, yielding a muddy limestone [49] (see Appendix I, The Fifth Alchemical Invention). Water eases disaggregation, making the limestones ideal for stone making, and the aluminous clay itself produces a dramatic result in combination with caustic soda and lime. Using aluminous clay instead of the required amount of mafkat, the material of the process most difficult to obtain was indeed eliminated for building the pyramid. Mafkat was required only for stones of high quality, such as stone vases. By eliminating the mafkat, Imhotep’s simple innovation enabled the enormous leap from small-scale funerary applications to the massive scale of the pyramids.

Small mud-brick molds with different sizes were filled, as they had been for Khasekhemwy to produce the pharaoh’s Palace of Eternity. But for the first time, the mud-brick molds were being filled with muddy limestone concrete and, as for the making of pisé, the material was rammed with a pestle. When, two decades ago, I started this study, I introduced the notion of “ cast-stone ”. Several magazine writers exaggerated this description and their headlines went far beyond by emphasizing on “ ... pouring a Pyramid ” (see in note [40]). Casting a fluid or pouring blocks or bricks require sophisticated molds like those implemented for the making of stone vases (poured) or statues. I am presently introducing a slightly different and more feasible technology. It is connected to the packed-earth (rammed earth) or pisé tech- nique. This more practical method is developed in several following chapters.

The new stone bricks, produced in five or six different sizes, were dried in the shade to avoid premature cracking, demolded, and transported to the construction site. The alchemically made stone bricks were used to produce a huge Enclosure and a square mastaba with its sides oriented to cardinal points. The Enclosure comprises limestone bricks of six different heights (Fig. 44). The burial chamber was un- derground. The mastaba was covered with small casing bricks of smooth limestone, and the sacred monument was considered to be complete.

Figure 44: Six heights of limestone bricks measured in Zoser's pyramid Enclosure at Saqqarah; increase of height in per cent compared to brick nr. VI.

Some time passed, and the stone bricks showed no sign of cracking. The pharaoh no doubt soon desired to make additional use of the new building material. Imhotep drew up plans to enlarge the mastaba. First, ten feet of agglomerated limestone were applied on each of its sides. Then, a more elaborate plan was devised. A twenty-five foot extension on its eastern face transformed the square mastaba into a rectangular shape, and the project was again brought to a close (Fig. 45).

Figure 45: Successive stages of construction of Zoser's pyramid are the Mastaba (M) and elaboration on the design (P1 and P2, after J.P. Lauer).

A later inspection would show that the stone under the weight of the mass showed no sign of cracking. King Zoser and Imhotep conferred again, and a plan was devised to heighten the structure to two tiers. Additional subterranean chambers, a shaft, and corridors were also dug.

As the size of the structure increased, the size of the bricks increased, maintaining, however, the five-six size distribution of the height within the construction (Fig.46). We are witnesses to dramatic design alterations inevitable with all revolutionary technological breakthroughs.

Figure 46: To construct Third Dynasty pyramids, worker (a) rammed limestone bricks in different wooden molds, (b) transported the bricks to the construction site, and (c) built the pyramids in inclined layers made of different brick sizes.

The more extraordinary their architectural wonder became, the more they built upon it. The amount of agglomerated stone that could be made would have appeared endless. A transformation into a four-tiered structure was followed by another construction phase in which the final form of a six-tiered pyramid, sixty meters (196 feet) high emerged. Its design included internal walls and inclined stone layers to provide great stability.With great skill and ingenuity, Imhotep incorporated all of the engineering and artistic methods the nation had derived from countless decades of building with wood, bundles of reeds and stalks, and sun- dried silt brick.

The final outcome was an extraordinary funerary complex. The Heliopolitan religious doctrine profoundly influenced its architectural form and the symbolism of its motifs. The design theme incorporated mythology which preserved and amalgamated Egypt’s most ancient and cherished cosmological beliefs. Heliopolitan theology taught that in the beginning, a primordial megalith, known as the Ben Ben (benben), arose out of the waters of Chaos. The benben represented the hill or mound upon which Creation began. The benben has been interpreted to symbolize dense, primeval physical substance or matter.

The Creator appeared on the benben in human form, as Atum, the personification of the Sun, or in the form of Bennu, the phoenix of light. Out of elemental chaos the Crea- tor separated the darkness from the waters. The Creator formed a trinity after having created himself and Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture. Tefnut and Shu procreated Geb, the earth, and Nut, the heavens. Four other deities were created, and all of the gods together made up the Heliopolitan Enneade. In later times, the Greek philo- sopher Empedocles (c. 495 - 435 BC) recognized in the pri- mordial Egyptian gods personifications of air, water, earth, and fire. Empedocles, and alchemists of later eras, held that these were the indestructible elements that composed all matter.

James Henry Breasted (1886 - 1935), founder of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, first recognized that the pyramids themselves are representations of the benben. After the first Heliopolitan temple was built, Egypt had adopted the ideology that the benben, or stone symbolic of the Sun god, was located beneath the temple.

The theogonic theme appears in subterranean chambers of King Zoser’s pyramid.Special chambers are lined with blue ceramic tiles in patterns depicting the primeval reed marsh from which vegetable life first emerged. Blue was the color symbolic of the Creator, and the blue glaze on the tiles imitated chrysocolla, the mafkat mineral indicative of Creation. With the exception of this monumental first pyramid, the artistic theme depicting the events of Creation was preserved only in the holy of holies of the great Sun tem- ples.

In a specially designed room a life-size stone statue of Zoser seated upon his throne represented his eternally reigning spirit or ka. When this statue was found by archaeologists, it was intact except for damage to the eyes and surrounding facial area. The eyes were probably made of semiprecious gems, which would most likely have been pillaged when the tomb was plundered. Certain stone statues of the Old Kingdom now in the Louvre and the Cairo Mu- seum are greatly admired for their inlaid eyes, a technique offering extraordinary realism and easily afforded by using alchemically made stone. Other rooms held the 30,000 stone vessels of Khnum, agglomerated using aggregates of schist, breccia, granite, diorite, and various other stones .

Surrounding the pyramid, a wall with clean architec- tural lines, originally more than thirty feet high, encloses more than a square-mile area.A characteristic of the smooth stone, encasing the wall and now mostly removed, is that it appears to be polished. The wall protects an elegant entrance colon- nade, great courts, large buildings, a mortuary temple, and ceremonial altars and shrines. The enclosed area is virtually an entire town. The design character of the enclosure wall resembles contemporary architecture, and did, in fact, in- fluence a style of twentieth century architecture. European architects visiting Saqqara earlier in the century found the enclosure wall a refreshing, appealing diversion from ornate Victorian architecture. They left with the inspiration for a style of architecture that we now consider modern and take for granted.

It was the pride of Egypt. Zoser’s funerary complex, with its towering pyramid and exquisite artistry, was unprecedented in the history of the world. Throughout Egyptian history the time of Imhotep was looked on as an age of great wisdom. Like the First Time event of Creation, as it was called, and the founding or amalgamation of the Egyptian nation by the first pharaoh, King Menes, the construction of the Step Pyramid was viewed as another first time event of great importance.

-----------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment