16th Annual J.B. Rudnyckyj Distinguished Lecture

Friday, November 7, 2008

The U of M Archives & Special Collections

331 Elizabeth Dafoe Library

The Holodomor: Reflections on the Ukrainian Genocide

By Dr. Roman Serbyn

Professor Emeritus, Université du Québec à Montréal

By Dr. Roman Serbyn

Professor Emeritus, Université du Québec à Montréal

“Starvation in Ukraine was brought about in order to reduce the number of Ukrainians, resettle in their place people from another part of the USSR, and in this way kill all thought of independence.” 1 This insightful assessment of the Great Famine came from a member of the Communist party by the name of Prokopenko, and was uttered before a group of collective farmers. A plenipotentiary of the Sakhnovshchynsky rayon executive committee (Kharkiv oblast), Prokopenko was irritated that the authorities “had smothered our good workers and sent us all sorts of rubbish.” There is little doubt that he was well informed about the tragic events in which he must have participated. He well understood the significance of the deliberate starvation of the Ukrainian farmers and his description of the catastrophe reads like an indictment of the sort of act that a decade later would be called genocide. One is struck by the uncanny resemblance between the definition of the crime in the UN Convention and Prokopenko’s assessment of the Ukrainian tragedy.

Article II of the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide defines “genocide” as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”.2 The two main elements of the definition are the “intent to destroy” and the identity of the victim group. Prokopenko’s statement fulfills both requirements. The claim that the famine was brought about for a purpose shows that the crime was intentional; the identification of the victims as Ukrainians puts them in the national or ethnic group. The Convention does not require the naming of the perpetrator and Prokopenko does not name one, but the identity of the culprit leaves no doubt: only the Communist party was in a position to commit the crime, and the ultimate responsibility belonged to him who held the levers of power. The UN document does not require the establishment of motives for the crime. However, motives explain the act and help to determine the perpetrator’s intent. In Prokopenko’s case, they also indicate the victim’s identity. The “reduction of the number of Ukrainians” was meant to facilitate the transfer ethnically foreign populations, weaken the Ukrainian element in the Ukrainian republic and ultimately “kill all thought of independence”. Such was Prokopenko’s perception of what transpired and what it signified, but these claims have to be substantiated by the available documentation?

The first Western scholar to provide a conceptual framework for analyzing what we now call “the Holodomor” was no other than Raphael Lemkin, a renowned authority on international criminal law, who coined the term “genocide” and prevailed upon the United Nations to adopt the “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide”.3 Born in 1900 to a Polish-Jewish farming family near the old Rus town of Volkovysk, now in the Grodno province of Belarus, Lemkin studied linguistics and law at the Lviv University of Jan Cazimir, and later worked as assistant prosecutor in Berezhany and Warsaw. He was thus well acquainted with Ukrainian affairs, and knowledgeable of the situation in the USSR, having twice translated Soviet criminal law. Fleeing Poland as the Nazi and Communist empires invaded the country in 1939, Lemkin eventually settled in the United States, where he died in 1959. In March 1953 he wrote an article for the Ukrainian Weekly in which he urged his readers to “use every opportunity to keep the eyes of the world on Soviet genocide.” And he considered the “coming anniversary of the 1933 deliberately organized famine ... a good occasion to further explain Soviet genocide.”4

The 20th anniversary of the Great Famine was commemorated in grand style in New York on Sunday, 20 September. According to the New York Times, 10,000 Ukrainians gathered at Washington Square, “as their compatriots had done on Nov. 18, 1933”, and marched “up Fifth Avenue to Thirty-fourth Street and hence to the meeting place on Eighth Avenue.” 5 The Manhattan Center took in 3,000 persons; the overflow gathered on the sidewalks at Thirty-fourth Street. The assembly included prelates of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, officers of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America and invited guests. Congressman Arthur G. Klein and Professor Raphael Lemkin delivered speeches. The Times report only mentioned Lemkin’s reference to the crime “employed 100 years ago against the Irish”. The Ukrainian Weekly was more explicit: “Prof. Lemkin reviewed in a moving fashion the fate of the millions of Ukrainians before and since 1932-33, who died victims of the Soviet Russian plan to exterminate as many of them as possible in order to break the heroic Ukrainian national resistance to Soviet Russian rule and occupation and to Communism.”6 Lemkin’s 1953 address at the Manhattan Center is most likely the text, which has recently come to light in the New York Public Library (NYPL).

A part of Lemkin’s archives are stored at Manuscripts and Archives Division of NYPL. The box, which contains various materials for his unpublished three-volume History of Genocide, holds a folder with eight pages entitled “Soviet Genocide in the Ukraine”. 7 The typescript is of particular interest for the study of comparative genocide and of Ukrainian genocide in particular. Lemkin favored a wide interpretation of genocide, and included among the victims political and social groups. However, once the UN General Assembly adopted a convention with a more restrictive definition, Lemkin accepted its parameters and, while not abandoning his own convictions, developed an analysis of the Ukrainian tragedy in conformity with the UN criteria. In line with the UN Convention, Lemkin claimed that the Ukrainian catastrophe was “not simply a case of mass murder,” but “a case of genocide, of the destruction, not of individuals only but of a culture and a nation.” Now while “destruction of a culture” does not qualify as genocide under the UN Convention, “destruction of a nation” certainly does. And it is this second element that Lemkin stresses in his analysis.

The chief merit of Lemkin’s approach to the Ukrainian genocide lies in his methodology — the analysis of the crime as a four-pronged attack on the Ukrainian nation. “The first blow is aimed at the intelligentsia, the national brain, so as to paralyze the rest of the body.” Large numbers of Ukrainian “teachers, writers, artists, thinkers, political leaders, were liquidated, imprisoned or deported.” He notes that in 1931 alone, 51,713 intellectuals sent to Siberia. Concomitant with the attack on the intelligentsia was the Soviet offensive against the Ukrainian Church, which Lemkin calls the “soul” of Ukraine. “Between 1926 and 1932, the Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church, its Metropolitan (Lypkivsky) and 10,000 clergy were liquidated.”

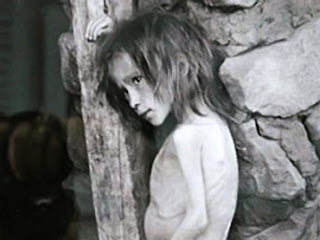

“The third prong of the Soviet plan was aimed at the farmers, the large mass of independent peasants who are the repository of the tradition, folklore and music, the national language and literature, the national spirit of Ukraine. The weapon used against this body is perhaps the most terrible of all — starvation. Between 1932 and 1933, 5,000,000 Ukrainians starved to death.” Lemkin emphasized the national attributes of the peasants’ identity — their role as repository of “the national spirit of Ukraine”. It was this “national spirit” that Stalin feared and decided to eliminate. Lemkin quotes Stanislav Kosior, the head of the Communist party of Ukraine: “Ukrainian nationalism is our chief danger.”8 Lemkin’s comment: “It was to eliminate that nationalism, to establish the horrifying uniformity of the Soviet state that the Ukrainian peasantry was sacrificed.” Significantly, Lemkin rejects the “peasantist” or socio-economic interpretation of the famine. He rejects the “attempt to dismiss this highpoint of Soviet cruelty as an economic policy connected with the collectivization of the wheatlands, and the elimination of the kulaks, the independent farmers.” He notes that “large-scale farmers in Ukraine were few”, there was grain in government granaries, thousands of acres of wheat “were left to rot in the fields”, and the much-needed crop was exported abroad. “The fourth step in the process consisted in the fragmentation of the Ukrainian people at once by the addition to Ukraine of foreign peoples and by the dispersion of the Ukrainians throughout Eastern Europe. In this way, ethnic unity would be destroyed and nationalities mixed.” Such were, claims Lemkin, “the chief steps in the systematic destruction of the Ukrainian nation, in its progressive absorption within the new Soviet nation.”

Prokopenko’s and Lemkin’s perceptions of the Ukrainian catastrophe are strikingly similar: the same classification of the victim group as Ukrainians rather than peasants; identical insight into Stalin’s motivation — to prevent the Ukrainian nation from seeking independence; similar understanding of the Communist regime’s intent to destroy a portion of the Ukrainian population. Writing after the more recent Holocaust, which he had studied and analyzed in depth, and conscious of the fact that history has known many genocides, Lemkin was in a position to make insightful comparisons between the Jewish and Ukrainian calamities. With regard to the extermination tactics of the Nazi and Communist regimes, he notes that the Communist had not applied “the pattern taken by the German attacks against the Jews,” because the Ukrainian “nation is too populous to be exterminated with any efficiency.” “However its leadership, religious, intellectual, political, its selected and determining parts are quite small and therefore easily eliminated, and so it is upon these groups particularly that the full force of the Soviet axe has fallen, with its familiar tools of mass murder, deportation and forced labor, exile and starvation.” Thus, while “there have been no attempts at complete annihilation, such as was the method of the German attack on the Jews”, the threat to the Ukrainian nation was no less serious. If “the intelligentsia, the priests and the [independent] peasants can be eliminated, Ukraine will be as dead as if every Ukrainian were killed, for it will have lost that part of it which has kept and developed its culture, its beliefs, its common ideas, which have guided it and given it a soul, which, in short, made it a nation rather than a mass of people.”

Prokopenko’s testimony and Lemkin’s conceptualization are corroborated by eyewitness reports, Western diplomatic dispatches, and the Soviet documents from Ukrainian and Russian archives. Research on the Ukrainian genocide can develop in new directions. Simultaneously with the famine in the countryside, a physical and spiritual destruction of Ukrainians as an ethno- national group was taking place in the growing urban centers of the Ukrainian SSR; from the Ukrainian republic it spread to the eight million Ukrainians residing in the RSFSR. During the 1920s, the migration from the predominantly Ukrainian countryside to the Russified industrial centers intensified the effects of the official policy of indigenization and escalated the process of urban Ukrainization. The situation changed radically at the end of the decade, when the cities once more became agents of the Russification of the fleeing Ukrainian rural population.

The genocide against the Ukrainians began with the destruction of the Ukrainian elites. It was carried out on two levels: a) the decimation and cowing of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, concentrated primarily in urban centers, and b) the dispossession of the wealthier and more dynamic farmers and their exclusion from the village community. In the fall of 1929, the GPU arrested 700 Ukrainian intellectuals and accused them of belonging to the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” (SVU), a Petliurist organization that the GPU put together for the occasion. Next March, 45 of the accused — former ministers of the Ukrainian indepedent government, academicians, professors, various political and cultural leaders associated with the short-lived independent Ukrainian state were put on trial. Their “counterrevolutionary” activities included organizing cells “in the villages and rural centers” and conducting propaganda to separate Ukraine from the USSR.9 The purpose of the show trial (held at the Kharkiv Opera House, was to terrorize the Ukrainian intelligentsia, and prevent it from siding with the peasantry and providing leadership during the regime’s attack on the latter’s way of life. Most of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to 10 year of incarceration in the Gulag, where many later perished. It should be noted that even though there was no SVU network, Ukrainian farmers did maintain spiritual ties with the Ukrainian intelligentsia and looked up to it. In March 1930, Vsevolod Balitsky, the GPU head in Ukraine, reported to Moscow that in some villages peasants expressed concern over the health of the Academician Efremov, the alleged head of the imaginary SVU, sang “Shche ne vmerla Ukraina” (“Ukraine has not died yet” – national anthem), and organized disturbances “under the slogans of SVU”.10

The SVU trial was only the first of a series of attacks on Ukrainian elites. Gradually the net expanded and the focus shifted from Ukrainian independentist and nationally conscious elements to pro-Soviet and Communist cadres, each in their turn suspected of waning loyalty to the regime. In January-February 1930, the GPU arrested 46 functionaries in Ukrainian economic institutions and accused them of promoting kulak and SVU agenda to wreck the Soviet economy. Members of the alleged organization were tried that June and sentenced to various terms imprisonment.11

In the second half of 1930, a pre-emptive GPU move against a “general Ukrainian military uprising”, discovered “counterrevolutionary plots” of farmers and officers’ organizations. That fall, the GPU fabricated a “Ukrainian National Center” (UNTs), consisting of former members of outlawed Ukrainian political parties. At the same time, a major military plot was “uncovered” among the officers of the Ukrainian Military District (UVO); 328 officers were condemned to death or long terms of imprisonment, while the whole officer corps in Ukraine was thoroughly purged. A GPU report of 27 December 1930 complained: “Kulak elements constantly try to exert influence on Red Army men” and even on certain units of the GPU; their influence was noticed “particularly in those units, which are stationed in the regions where they were recruited”. Local recruitment created dangerous closeness between the army and the local population. The purge of the Red Army in Ukraine was meant to counteract the soldiers’ anger at the collectivization, deportation of Ukrainian farmers, and murderous requisitions. In January 1931, the GPU crushed the “Leftbank Headquarters of the Insurgent Army for the Liberation of Ukraine,” sentencing twelve ringleaders to death and executing many other “members”.12 By 1932 the preventive purges reached the Communist Party of Ukraine and the Ukrainian administration.

In 1930 the GPU forced the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church to proclaim its own liquidation. Many of its clergy and faithful were persecuted and exterminated. Since the Genocide Convention recognizes the destruction of a religious group as one form of genocide, case could be made for religious genocide in Ukraine. But, in fact the complete annihilation of the Ukrainian Church had less to do with its religious nature than with its “autocephalous” status vis-à-vis the Russian Orthodox Church. For, while the latter was also persecuted, it was not liquidated. For this reason, the elimination of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church falls rather into the category of national genocides – the primary motive was to deprive the Ukrainian nation of its spiritual leadership, of its “Soul”.

The natural leaders of the rural population were the better educated, more enterprising and richer farmers, called kurkuli (kulaks in Russian). They had the most to lose from collectivization and resisted it the most stubbornly. Stalin expected the poor peasants to regard the kulaks as class enemies and help the authorities confiscate their property for transfer to the collective farms. On 27 December 1929 he announced a new policy — “the elimination of kulaks as a class.” The kulaks were dispossessed, driven out of their homes, and either given poorer land outside the kolkhoz, resettled in another part of the country, or exiled to Russia’s Far North. There were two waves of dekulakization: the main one in the early months of 1930 and a smaller one a year later. In 1934 Kosior, reported that 200,000 households, or about one million souls, had been dekulakized in his republic. Several hundred thousand were deported beyond the borders of Ukraine. Many thousands perished en route or at the unhealthy destination of their exile. Deportation also took place in the Kuban, where whole Ukrainian stanytsias (Cossack settlements) were transferred to the Russian Northlands. Dekulakization deprived Ukraine of its best farmers and custodians of its national culture and spirit. As dekulakized farmers were barred from collective farms, in socio-political terms, this meant that the peasants lost the most dynamic members, who could provide leadership in the struggle with the repressive regime.

The overwhelming majority of the victims of the Holodomor were the so-called “middle” and poor peasants (the kurkuli made up only 3-5 % of the farming population), and they died mainly from starvation and related illnesses. It was, thus, understandable that the memory of the Great Famine and the subsequent debates and controversies that developed around it concentrated on the famine and the peasants. Even the neologism “Holodomor”, coined from “holod” (hunger, starvation, famine) and “moryty” (to enfeeble, exhaust, destroy), which replaced the older designation of “the Great Famine”, is only very slowly evolving from its etymological sense of “extermination by hunger” to designate the more embracing notion of “Genocide against the Ukrainians”, just as “the Holocaust” has come to mean “Genocide against the Jews”. The habit of focusing on the “famine” as the crime and the “peasants” as the victims tends to obfuscate the true scope of Stalin’s destructive policies towards the Ukrainian nation and to think of Holodomor in terms of genocide.

The reasons which have been given for the Ukrainian famine extend from devastating natural causes to deliberately planned and viciously executed government policies. Analysts usually focus on the collectivization and dekulakization, mandatory grain deliveries and repressive measures against recalcitrants. All these and other factors played a role but the key agent was Stalin. Having overcome his opponents in the Party hierarchy, Stalin moved to don Lenin’s mantle as leader of world socialist revolution and to turn the USSR into the main mover in this endeavor. To this end he decided to transform his underdeveloped multinational empire into a unified and disciplined military force, supported by a highly developed industry. The needed capital would be provided by Russia’s traditional sources: the export of raw materials, especially grain. Buying grain from peasants on the free market for resale abroad would not be profitable; requisitioning it from independent peasants, as was done after the revolution, would be inefficient and socially dangerous. A more effective method was mandatory “state procurement” from “collectivized farms”. The crops would be stored together and the state could “procure” as much of it as it wanted. Stalin knew that the collectivization would not go smoothly, especially in Ukraine and the Kuban, where the Russian “obshchina” was unknown, and where rquisition would be regarded as a form of economic exploitation by Moscow. The “socialist revolution” in the countryside would inevitably disrupt and diminish agricultural production, making forced “procurement” that much more onerous. All these considerations were among the main reasons for dekulakization, a preemptive elimination of the hostile peasantry’s potential leaders.

At the November 1929 Plenum of the Central Committee, Stalin declared spontaneous collectivization to be sufficiently advanced to justify the “total collectivization of entire districts.” The plenum decided to mobilize 25,000 industrial workers (including 7,500 in Ukraine) to be assigned chairmanships of large kolkhozes or given other administrative jobs. Additional cadres were periodically called up, and eventually the overall number tripled. By the spring of 1930, Ukraine had some 50,000 of these activists with special powers to organize, punish, and terrorize the peasants. In November 1929 only 522,500, or 10.4%, out of the total of 5,144,800 Ukrainian households were members of collective farms. The escalation of the plan raised it to 30.7% by 1 February 1930 and 62.8% (with 68.5% of the arable land), five weeks later. The spectacular success was achieved with unrestrained violence and at the cost of many lives. As peasant solidarity grew, a reign of terror descended upon the countryside. Government plans were carried out, encouraged by such slogans as “let them all die, but we will collectivize the district 100%.”13

Rich and poor resisted in any way they could. Some slaughtered their animals; others “self- dekulakized” and fled to industrial centers. The protests increased in violence. Enforcers of dekulakization and collectivization were attacked and driven out of the villages. Women led many of the disturbances. Leaflets appeared with social, political, and national slogans. Between 20 November 1929 and 7 April 1930, 834 flyers were picked up in Ukraine proclaiming: “Time to rise up against the Moscow yoke,” “Ukraine is perishing, my Ukrainian brothers,” “Petliura told us the truth — time to wake up, time to rise up.” By 6 February 1930, the OGPU arrested 15,985 conspirators in the USSR, 5,171 of them in Ukraine.14 GPU reports warned of a general insurrection planned by Petliurite organizations for the summer of 1930. Some insurrections grew to thousands of people and had to be put down by military force.15

In the face of a general economic meltdown and widespread social upheaval, Stalin staged a tactical retreat. On 2 March 1930, Pravda carried his article “Dizzy from Success,” in which he blamed local cadres for the excesses and errors and reaffirmed the principle of free membership in the kolkhozes. He abandoned the harsher “commune” system and settled for the looser “artel” association, which allowed collective farmers to keep a small plot of land, a house, and some domestic animals. These vestiges of private property, especially the cow, would be their main support in the famine years. Stalin’s “retreat” and the disorientation of the cadres encouraged the peasants to leave the kolkhozes, taking their land, cattle, and farming implements. By September 1930 only 28.4% of households and 34.8% of arable land remained in the Ukrainian kolkhozes. The decollectivization was resisted by the local authorities and the OGPU recorded 13,756 disturbances in the USSR for that year, of which 4,098 (30%) took place in Ukraine. In 10,071 of them (3,208 in Ukraine) the OGPU counted 2.5 million participants (one million in Ukraine).16 Poorly armed, without proper organization and coordination, the sporadic uprisings were eventually put down. The rebels were punished and collectivization resumed. By 10 March 1931, 48.5% of Ukrainian households and 52.7% of the arable land were back in the kolkhozes, and seven months later the figures rose to 68.0% and 72.0%, respectively. In the grain-producing steppe region of Ukraine, 87% of households were collectivized. When the first wave of famine swept the republic in the winter of 1931-1932, most of the peasantry was already collectivized.

Concomitantly with the “struggle for collectivization” and the move to “liquidate the kulaks as a class,” the Party launched an equally vigorous “struggle for bread,” which was, after all, the main short-term economic goal of Stalin’s collectivization. High grain procurement quotas were established for both the socialiazed (collective and state farms) and the private (individual farms) sectors. The same people who had sent kulaks into exile and forced the peasants into kolkhozes now enforced the confiscation of the peasants’ grain. In 1930, the peasants fought against state serfdom, but still tilled the land, and the harvest was good. Overall grain production for the USSR was 73-77 million tons (hereafter — m.t.), with 23 m.t. for Ukraine. The state collected 22 m.t., including 7.7 m.t. from Ukraine. At the same time, Soviet grain exports rose from 30,000 tons in 1928 and 180,000 in 1929 to 5,832,000 in 1930 and 4,786,000 in 1931.17 Stalin’s assurance that collectivized agriculture would provide more “marketable grain” was vindicated.

In 1931, however, the overall grain production fell by about 15 million tons. Adverse climatic conditions were partly to blame for poor crops, but the decline was mainly due to the ferocious confrontation between the state and the agricultural producers in both the collective and private sectors. Incompetent administrators of collective farms, chosen for party loyalty rather than professional competence, mismanaged and brought the farms to ruin. Wages for trudodni “labour days” fell in arrears, and collective farmers lost interest in their work. Apathy and negligence reigned. The cattle was not properly cared for and perished in great numbers. Sabotage increased. Much grain was lost in the fields, during threshing and transportation. While the peasants resisted their enslavement, a new specter appeared on the horizon —starvation. In 1929 and 1930 they still had some reserves, but by 1931 these had been depleted, and the imposition of high delivery quotas left them little for food, animal feed, and seed material for next season’s sowing.

Towards the end of 1931 the famine intensified across Ukraine, and by the summer of 1932 hundreds of thousands died from hunger. Peasant protests changed from fighting collectivization to resisting procurement. Peasant flight from villages increased. In January-February 1932, 89,300 peasants left their farms in the Dnipropetrovsk oblast alone.18 Many went to Russia, where food was available. In April the Voronezh authorities complained to their Donetsk counterparts about the influx of “whole families with children and frail old people,” who had been “buying, trading, and begging for bread,” and “cramming railway stations,” since February. “Only in the last several days 12 individuals were buried; they had come for bread from neighboring Ukrainian raions.”19 On 26 April Kosior informed Stalin about cases of starvation and “individual villages that are starving.”20 On 10 June 1932, after inspecting the Ukrainian countryside, Heorhy Petrovsky, the head of the Ukrainian state, and Vlas Chubar, head of the Ukrainian government, sent separate reports to Moscow detailing the appalling situation and pleading for one or two million poods (i.e., 16,361-32,722 t.) of grain.21 They argued that starvation had begun in December 1931. Local authorities lacked resources. Peasants pestered Petrovsky: “Why did you create an artificial famine,” “why did you take away the seed material?” Theft was spreading, and kulaks and Petliurites were gaining support from the “middle” and poor peasants. An exodus was underway to Russia, in search of food. Petrovsky warned that unless assistance was provided, starvation would drive the peasants to pick unripe grain and put the harvest in jeopardy.

By alerting Stalin to the economic and political difficulties, the Ukrainian leaders hoped to convince the General Secretary to make new concessions. But Stalin rejected their plea and blamed local mismanagement for the fact that “fertile districts in Ukraine, despite the fairly good harvest [in 1931 – R.S.], have found themselves in a state of impoverishment and famine.”22 He proposed a top level conference to discuss “the organization of grain procurement and the unconditional fulfillment of the grain-procurement plan,” and insisted that the first secretaries of grain-producing regions be made personally responsible for the grain delivery. On 21 June 1932, Stalin instructed Kharkiv to carry out “at any price” the plan for grain delivery, between July and September.23 “Unconditional fulfillment” and “personal responsibility” became the watchwords in the coming procurement campaign, which culminated in the genocidal famine.

The III Conference of the CP(b)U, which opened on 6 July under the watchful eyes of Molotov and Kaganovich, was wholly devoted to the upcoming harvest and grain procurement. Declarations from regional leaders that the farmers were starving, that much land lay fallow, and that the losses during harvesting would be higher than last year’s by 100 to 200 m.p. did not bend the resolve of Stalin’s envoys. They forced the conference to adopt a resolution “to carry out in full and unconditionally” the proposed grain delivery plan.24 Harvesting had begun with little success because the peasants were starving. On 6 July Izvestiia prepared a confidential report about the famine, with excerpts from the letters it had received, mainly in Ukraine. “Why is Ukraine starving like this?” complained one reader. “Why is there no similar famine in other republics? How do you explain that there is no bread in grain-producing Ukraine, while Moscow has as much of it as you want?” One letter ended with a threat: “If war comes, we shall not defend the Soviet power.”25 Two weeks later, the OGPU claimed that Ukraine had the highest number of anti-Soviet disturbances. Another OGPU report, dated 5 August, spoke about the liquidation of eight nationalist groups in Ukraine, two of which consisted of former members of the outlawed Ukrainian Communist Party (UKP – non-Bolshevik). They proclaimed a leftist program and conducted systematic activities among the members of the CP(b)U.26

In reaction to the Ukrainian events, Stalin began to devise a suitable mechanism to ensure that his orders on grain deliveries would be carried out.” Writing on 20 July to Kaganovich and Molotov, the General Secretary proposed to introduce a law that would make kolkhoz property equal with state property, render theft of this property “punishable by a minimum of ten years’ imprisonment, and as a rule, by death”, and revoke the right of amnesty in these cases.27 Six days later he elaborated on the future decree, remarking cynically: “We must act on the basis of law (‘the peasant loves legality’), and not merely in accordance with the practice of the OGPU, although it is clear that the OGPU’s role here will not only not diminish, but, on the contrary, it will be strengthened and ‘ennobled’ (the agencies will operate ‘on a lawful basis’ rather than ‘high-handedly’).”28 The judicial system was to be given a task of enforcing Stalin’s genocidal policies. The Party-State decree on socialist property, dubbed by the peasants “the 5 ears of corn law” was issued on 7 August 1932.29 It became the main legal instrument for the implementation of Stalin’s condemnation of millions of farmers to slow death by starvation.

The decree on state property applied to the whole Soviet empire, but its primary target was Ukraine. Writing just four days after its promulgation, Stalin ordered Kaganovich to have the Central Committee draft a “letter-directive” to “party, judiciary, and punitive organizations” explaining the decree and the methods for its implementation. He then addressed the Ukrainian problem: “The most important thing right now is Ukraine. Ukrainian affairs have hit rock bottom.” The republic had problems everywhere. “Things are bad with regards to the party.” 50 [out of 450 – R.S.] regional party committees, in two [out of six – R.S.] oblasts (Kyiv and Dnipropetrovs’k) opposed the grain-procurement “deeming it unrealistic”. The situation in other regions was not any better. The soviets [administration – R.S.] are unreliable. Kosior and Chubar are not up to their tasks. The GPU is incapable of “leading the fight against the counterrevolution in a large and distinctive republic as Ukraine. 30

Then, Stalin brandished the specter of Ukrainian separatism: “If we don’t undertake at once to straighten out the situation in Ukraine, we may lose Ukraine.” He had only contempt for the CP(b)U, which numbered 500,000 members (“ha-ha”, he snickers), but was infiltrated by “agents of Pilsudski” and “quite a lot (yes, a lot!) of rotten elements, conscious and unconscious Petliurites.” Betraying his anticipation of dire consequences from his murderous property decree, Stalin warns: “The moment things get worse, these elements will waste no time in opening a front inside (and outside) the party, against the party.” There was, of course, no danger from Poland, which had only recently (25 July 1932) signed a nonaggression treaty with the USSR, and the surviving Petliurites were too weak to matter. But the growing disillusionment of Ukrainian Communist cadres was dangerous. The threat of insurrection could become a reality if the expected famine (Stalin insinuated this probability in his allusion to “the moment things get worse”) succeeded in binding the threatened middle and lower cadres of the CP(b)U with the tormented peasantry. Stalin intended to consolidate his control over Ukraine and transform the republic “into a real fortress of the USSR,” against external and internal enemy. Otherwise, he insisted, “we may lose Ukraine.” Ukraine needed a strong hand to prevent an alliance between the CP(b)U and the peasants. Stalin toyed with the idea of replacing Kosior and Redens, the GPU boss. Eventually Kosior was retained but reinforced with the hardliner Pavel Postyshev, and Redens was replaced by another hardliner— Vsevolod Balitsky.

By the end of the summer, the stage was set for Stalin’s genocidal blow against the Ukrainian nation: the maximum extraction of grain at whatever cost, the enslavement of the rural population, and a switch from Ukrainization to Russification. The 1932 harvest was even worse than that of the preceding year. Again, the confrontation between the state and its citizens at the time of sowing, weeding, and harvesting was the main cause. Weakened by hunger and discouraged by their unsuccessful struggle, the collective farmers would not and could not work as was necessary. The new tractors were not supplied in sufficient numbers to compensate for the loss draft animals. As the grain quotas became known, they provoked protests not only among the farmers but also local party worker and administrators, who also considered the new procurement plans unrealistic. Delivery regulations obliged the collective farms to fulfill their obligation to the state before responding to the needs of their members. Most collective farms did not give out any “advances” (in fact, earned wages for work-days-trudodni) and their members had to rely on the paltry yields of their meager plots, and the milk from their cows. Some conscientious kolkhoz chairmen refused to obey the plan and either tore up their party cards and fled, or countered direct orders with subterfuge. The farmers, terrified by last year’s horrors, tried to cheat the famine makers and the famine. They stole grain from the fields during wheat cutting, threshing, transporting and milling. The stronger and more enterprising farmers once again left their villages to seek food in urban centers or neighboring republics.

Grain procurement was not going well, and Stalin sent Molotov and Kaganovich on frequent missions to Ukraine and the North Caucasus to supervise the work and purge recalcitrant cadres. Sojourning in Kharkiv on 29 October, Molotov obtained Stalin’s acquiescence to a reduction in the grain procurement of 70 m.p. (1.15 m.t.), but obliged the Ukrainian Politburo to collect the grain quota in full. Grain from collective farmers’ private plots would be integrated into that of the kolkhoz. Molotov then sent top Kharkiv party leaders to the villages, not to organize famine relief but to supervise grain collection and purge local cadres, accused of siding with the “kulaks and Petliurites.” New regulations followed: kolkhozes and private farmers found guilty of “sabotage” were “blacklisted,” their village stores were closed and goods removed, while the punished peasants lost the right to buy and sell on the free market. Itinerant courts and special “troikas” were set up to apply the 7 August property law. Redens and Kosior were given the task of drawing up an operational plan for the “liquidation of the main nests of kulak and Petliurite counterrevolutionaries.”31

On 20 November, Molotov forced a resolution through the Ukrainian government concerning the confiscation grain and edibles and the repression of opposition.32 Grain delivery was to be completed by the end of the year and the storage of sowing material by 15 January 1933. Kolkhozes withholding deliveries would have all their grain reserves transferred to state procurement, irrespective of the purpose for which they were constituted. These kolkhozes (in fact, the majority) were forbidden to pay out “advances” for trudodni, and where such “illegal distribution” had already taken place, the grain was to be taken back for state procurement. Heads of collective farms were made personally responsible for carrying out these orders. The property law of 7 August was extended to all thieves of kolkhoz property, including the kolkhoz administration, bookkeepers, warehouse workers, etc. Kolkhozes that had permitted theft of kolkhoz grain were fined 15 months’ worth of meat taxes. Cows belonging to the kolkhoz and/or to their members would be sacrificed to pay the fine, and if that was not sufficient, potatoes and other edibles would be confiscated.

These resolutions left the collective and private farmers at complete mercy of the repressive organs and gave local activists a free hand in resorting to unrestrained violence. All grain that could be seized was taken from the farmers, no matter how they had acquired it—whether it was earned with “work days,” raised on private plots, bought or traded, or stolen from the fields. Nor did it matter if the owners were saving it for next season’s sowing or to feed their families. House searches were conducted and when activists found no grain, they took all the other edibles and left the families without any means of subsistence. On the basis of the 7 August law, farmers were arrested, abused, and tried for theft and sabotage. Collective farm chairmen, accountants, and other personnel were arrested, shot, or exiled for “squandering” kolkhoz property. Paying out trudodni before fulfilling the mandatory grain delivery was “misuse” of collective property. In November 1932, the GPU arrested 8,881 “squanderers” of kolkhoz wealth in Ukraine. Among them were 311 heads of collective farms and 702 members of kolkhoz administrations; 2,000 of the accused were labeled as former Petliurites and Makhnovists.33 From August to November, the GPU arrested 21,197 people in connection with grain procurement, and the militia held another 12,896 people, including 339 kolkhoz chairmen and 749 members of administrations.34

Kaganovich’s operations in the North Caucasus Territory (NCT), especially the Kuban region, proved particularly devastating. By 4 November three Cossack stanytsias were placed on the blacklist, and two weeks later Stalin approved Kaganovich’s request to deport 2,000 families for “maliciously sabotaging the winter sowing.” A GPU report of 8 November painted the Poltava stanytsia as a hotbed of Ukrainian counterrevolutionary activity since the early 1920s. The 400 stanytsia intellectuals were joined by “some Petliurites, who migrated this summer from Ukraine.” The spirit of the pro-Ukrainian Kuban Rada (anti-Soviet) was still present.35 A purge of cadres followed with particularly destructive proportions: 43% of the 25,000 party members in the Kuban were purged including 358 out of the 716 party secretaries. Up to 40% of the 120,000 rural party members may have been expelled.36

After two years of draconian grain procurements, Stalin could claim that his methods were winning the “struggle for bread.” At a party meeting, on 27 November 1932, he boasted: “The party has succeeded in replacing the 500-600 million poods [8.2-9.8 m.t.] of marketable grain, procured during the period of individual peasant holdings by our present ability to collect 1,200- 1,400 m.p. [19.6-22.9 m.t.] of grain.” The larger amounts were collected from the 1930 and 1931 harvests, but the 1932 harvest was small and the state could only get 18.5 m.t. Still, on 8 December the Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party (bolshevikk) (AUCP(b) approved the export of 100 m.p. (1.62 m.t.) of grain and planned to sell the same amount as it did the two previous years. Eventually exports had to be curtailed, but the USSR still shipped out a million and a half tons of grain, enough to feed six to seven million people. In the meantime, Stalin condemned all talk of famine, rebuking the Kharkiv party chief Roman Terekhov for raising the issue and telling him to write fairy tales for children instead. This was the official line for everyone to follow: there was no famine, and any talk of famine was only propaganda aimed at discrediting Soviet achievements. The procurement struggle continued throughout December and January. After confiscating everything that was easily detectable, flying brigades of activists went looking for hidden “treasures.” Official reports state that searches conducted in Ukraine from 1 December 1932 to 25 January 1933 uncovered 1.7 m.p. (27.800 t.) in 17,000 hiding places.37

Stalin’s conflict with Ukraine and the North Caucasus came to a head at the CC AUCP(b) meeting of 10 December 1932. After hearing reports on lagging grain deliveries by S. Kosior and B. Sheboldaev, the party boss of the NCT, Stalin accused the Ukrainians of pursuing an erroneous political line, demonstrating “spinelessness” and lack of perseverance in the struggle with the saboteurs. He then scathingly attacked Skrypnyk, the Ukrainian Commissar of Education for conducting an anti-Bolshevik Ukrainization policy and maintaining ties with nationalist elements.38 Stalin combined the “struggle for bread” with the “struggle against Ukrainian nationalism” and embodied it in a secret decree titled “On Grain Procurement in Ukraine, the North Caucasus, and the Western Oblast.”39 Signed on 14 December 1932, the document outlined three tasks: a) solve the grain procurement problem, b) eliminate counterrevolutionary elements, and c) curtail Ukrainization. The decree made the party and government heads of the three grain-producing regions personally responsible for completing grain procurement on assigned dates in January 1933. It demanded exemplary punishments of ten years in the Gulag for party leaders of Orikhiv raion (Dnipropetrovsk oblast) for “organizing the sabotage of grain procurement” and the deportation to the North of the entire Poltava stanytsia of the Kuban, also for sabotaging grain delivery. Demobilized Russian Red Army soldiers would be settled on the vacated land and receive the abandoned buildings, equipment, and cattle.

The document blamed Ukrainization for the difficulties in grain deliveries. Bourgeois nationalists, Petliurites, and supporters of the Kuban Rada had joined party and state institutions, set up their cells and organizations, and become directors, accountants, storekeepers, foremen in collective farms, and members of village soviets. They then sabotaged the harvesting and sowing campaigns. The party and state authorities in Ukraine and the Northern Caucasus were ordered to extirpate these counterrevolutionary elements and execute or deport them to concentration camps. Saboteurs “with party memberships in their pockets” also deserved to be shot. The document further alleged that a non-Bolshevik “Ukrainization” had been imposed on nearly half of the raions in the Northern Caucasus, even though it was "at variance with the cultural interests of the population." The verdict came in two parts. In Ukraine, Ukrainization would be continued, but would return to its original task of promoting the "correct Bolshevik realization of Lenin's nationalities policy," meaning integration and assimilation. The Ukrainian authorities were instructed to “expel Petliurite and other bourgeois-nationalist elements from party and government organizations," and "meticulously select and recruit Ukrainian Bolshevik cadres." In reality, this was a signal for the return to a more sophisticated policy of Russification.40

A worse fate awaited the Ukrainians in the North Caucasus Territory: they were subjected to a real national pogrom. By 27 December, the entire Poltava stanytsia was deported (2,158 families with 9,187 members)41 and resettled on 28 January 1933 with 1,826 demobilized soldiers.42 The same happened to other Cossack stanytsias. The Ukrainian language was banned in local administration, cooperative societies, and schools, and the printing of newspapers and magazines. On 15 December, the ban on the Ukrainian language was extended to all regions of the RSFSR. Stalin's anti-Ukrainization decree reveals the extent to which the dictator was ready to sacrifice Ukraine on the altar of Soviet great-power ambitions. The abolition of Ukrainization was a sop to Russian nationalists, especially in ethnically mixed regions of the RSFSR. As a result of the new aggressive Russification policy towards Ukrainians in the RSFSR, the census figures for Soviet Ukrainians outside the Ukrainian SSR declined from eight million in 1926 to less than four million in 1937.

During the months following the Politburo’s condemnation of Ukrainization, Ukrainians experienced some of the worst moments of their history. The litany of repressive measures is endless. On 15 December 1932, 82 raions were deprived of manufactured goods for not fulfilling their quotas of grain deliveries. Four days later, Stalin ordered Kaganovich and Postyshev back to Ukraine to help Kosior, Chubar, and Khataevich bring the grain collection to a successful conclusion. Kaganovich’s mission to Ukraine (22-29 December) had dire consequences for the republic.43 Stalin’s henchman accused oblast chiefs Terekhov and Stepansky of covering for their personnel and protecting the withholders of seed funds. With Stalin’s approval, Kaganovich prevailed upon the CC CP(b)U to rescind previous restrictions on the transfer of seed and other kolkhoz grain reserves to state procurement.44 Stalin’s earlier pronouncement on the sanctity of socialist property no longer applied to that of the kolkhozes. Now nothing that the collective farms or its members possessed could be considered inviolable, and the state could despoil them at will. Before returning to Moscow, Kaganovich had the Ukrainian Politburo send letters to the oblasts ordering the transfer of seed material to grain procurement.

To encourage peasants to reveal the “stolen” grain, Kaganovich promised, “peasants who voluntarily opened their pits would be granted amnesty.”45 Stalin borrowed the idea and sent it as a cynical New Year’s Address to the Ukrainian people. On 1 January 1933 the CC AUCP(b) ordered the Ukrainian Central Committee and the Ukrainian government to inform the Ukrainian farmers that those who voluntarily delivered to the state “previously stolen and concealed grain” would not be punished, but those who continued to hide it would be prosecuted to the full extent of the law, as envisioned by the decree on kolkhoz property of 7 August 1932.46 The peasants found themselves in a no-win situation. Those who denied having any grain would be searched and if found, the grain would be confiscated and the owner punished. Those who had hidden grain and surrendered it, would be left without any. In either case they faced starvation.

Thus began the fateful year of 1933, the genocidal culmination of Stalin’s war against the Ukrainians. Physically exhausted after several years of struggle and privation, the farmers of the Ukrainian SSR and the ethnically Ukrainian regions of the RSFSR were left completely vulnerable to the new onslaught of the communist regime’s destructive actions. During the winter, spring, and into the summer of 1933, uncounted millions died of hunger, cold, and the maladies that accompanied them. Previous repressions were intensified. “Dekulakization” (although no real kulaks were left) and deportations continued, on a smaller scale and mostly for political reasons. Arrests, beatings, and various cruelties flourished as before, only now the victims were weaker and less capable of resistance. It is this period in particular that has filled the pages of survivors’ memoirs and the eyewitness reports of foreign diplomats, journalists and other visitors who had the moral integrity to write the truth about what they saw. Heartrending descriptions of mothers killing one child to feed another, of human beings hunting other human beings are amply documented in scholarly and popular literature and need not be repeated here. What is more important is to examine the regime's behavior during this period.

On 22 January 1933 Stalin sent a secret directive ordering Ukraine, Belarus, and the neighboring regions of the RSFSR to prevent the exodus of peasants from the Kuban and Ukraine to the nearby regions of Russia and Belarus.47 The General Secretary complained that a similar flight of “Socialist-Revolutionaries” and “agents of Poland,” pretending to be looking for food, was not stopped the year before. He directed the party, state, and repressive organs of the NCT and Ukraine to prevent repetition of a such movement. All border crossings between Ukraine, the North Caucasus, and the rest of the USSR were ordered closed to peasants. The OGPU was instructed to arrest all farmers trying to flee Ukraine and North Caucasus, and after isolating the counter-revolutionary elements, send the rest back to their villages. This directive is perhaps the best available evidence of the dictator's genocidal intent against the Ukrainian people.

The instructions sent the same day by Yagoda, assistant director of the OGPU, to a dozen top Chekists in key regions, underscore the national character of this operation.48 Yagoda claimed that the departure of peasants was “organized by the remnants of the Socialist- Revolutionary and Petliurite counter revolutionary organizations uncovered by the OGPU [Emphasis added – R.S.].” Yagoda ordered the GPU of Ukraine, Belarus, and the NCT to “immediately arrest all [peasants] who were making their way from Ukraine and the NCT and submit them to thorough filtration.” Pickets were to be set up on all roads out of Ukraine and the NCT, and guards posted around railway stations. “Unrelenting counter revolutionaries” were to be sent to concentration camps, and the rest returned to their places of residence. Those who refused to return to their villages were to be sent to “special kulak settlements” in Kazakhstan. On 23 January, the Politburo of the CC CP(b)U resolved to carry out Moscow's orders, and Khataevich and Chubar forwarded the directive to the regions for implementation.49 Oblast authorities were told to warn farmers that they would be arrested if they left without permission. The GPU was ordered to instruct railway stations not to sell tickets to peasants with destinations outside Ukraine, without permission from the raion executive committee or a certificate of employment from construction or industrial enterprises. On 25 January, Sheboldaev issued similar orders for the NCT.50

The 22 January 1933 directive on border crossing was the culmination of a process, which, as we have seen from Petrovsky’s complaint to Stalin, had begun in the spring of 1932. Yagoda’s report to Stalin of 23 January 1933 mentions roadblocks against farmers of the North Caucasus as early as the November 1932. The Italian vice-consul in Batumi wrote on 20 January 1933 about local authorities forcing migrants to sell their last possessions to pay for the boat fare to Odesa .51 Documents show that Stalin monitored the operations as Yagoda reported them. With the implementation of the border directives “departures and the will to depart from villages diminished”. While 15,210 people left Dnipropetrovsk oblast between 15 and 23 January, only 1,255 departed between 25 and 31 January. Peasant who had fled before were rounded up. On 2 February, Yagoda informed the General Secretary that between 22 and 30 January the GPU arrested 24,961 people: 18,379 from Ukraine, 6,225 from the NCT, and 357 from other regions.52 By 14 February 18,166 people had been sent back to Ukraine from the Central Black-Earth oblast.53 A detailed table for 20 March 1933 shows 225,024 refugees detained by the OGPU, of which 196,372 or 87%, were sent back home to starve.54

To “strengthen” party leadership in Ukraine, on 24 January 1933 Moscow changed the first secretaries of the key grain-producing oblasts. Postyshev replaced Terekhov in Kharkiv, Khataevich relieved Stroganov in Dnipropetrovsk, and Razumov took Mairov’s place in Odesa. Postyshev was also named second secretary of the CC CP(b)U, while retaining his post as secretary of the CC AUCP(b), and Khataevich became one of the secretaries of the CC CP(b)U.55 In February Balitsky replaced Redens as head of the Ukrainian section of the GPU. With these hardliners in place, Moscow obtained direct and complete control over the party, state, and repressive organs of Ukraine. By the end of January, Ukraine and the Kuban were swept clean of all edibles; the peasants, the urban unemployed, and the old people and were dying by the thousands and tens of thousands. The Ukrainian nation was crushed, even though in the middle of March 1933 Kosior would write to the Kremlin that the famine still had not taught the collective farmers a lesson.56 The famine continued until 1934. On 14 February 1934 “food shortages” were reported in 46 raions of Ukraine, with 166 villages starving. In the Kyiv oblast 305 families were starving and 15 died of hunger.57

Contrary to a common misconception, references to the famine and the use of the term “holod” (“golod” in Russian) did not disappear from official documents, but it was only used in reports and correspondence sent up the administrative ladder and not in orders going to subordinates. On 5 March 1933 Krauklis, the GPU chief of Dnipropetrovsk oblast informed Balitsky that GPU inspections of 40 raions revealed famine in 378 villages with 7,291 families starving; 18,705 people were swollen from hunger, and 1,814 had already died.58 At about the same time Rozanov, the GPU head of Kyiv oblast, sent a statistical table, which showed that in the 42 raions of Kyiv oblast 93,936 adults and 112,199 children were starving, and 12,801 people had died from the famine.59 Two weeks later Balitsky instructed the oblast GPU chiefs to inform only the first secretary of the oblast Party organization, about famine-related topics, and to do so only verbally. He also gave orders not to leave any material on the famine lying around the office and not to compile detailed reports for the GPU of Ukraine, but only inform him (Balitsky) by personal correspondence. The GPU chief insisted that all sources must be thoroughly checked, because “Petliurite elements will try to disinform us.”60 Thereafter, internal reporting on the famine decreased, but did not completely disappear.

The XII Congress of the CP(b)U, held in January 1934, was an occasion for taking stock of the accomplishments of the last five years. Postyshev, the effective head of the party in Ukraine, reveled in the fact that 1933 had seen the “debacle of the nationalist deviation headed by Skrypnyk.” “Skrypnyk’s deviation,” Postyshev specified, “began to form itself into a complete system of national-opportunist view during the struggle for the liquidation of kulaks as a class.” As the class struggle intensified, “nationalist elements became particularly active in 1931-1932, and with every passing day infiltrated new fields of socialist construction.” The turnabout came after the resolution of 14 December 1932, condemning Ukrainization, and the 24 January 1933 criticism of the Ukrainian party by the CC AUCP(b). After that, concluded Postyshev, “when it was said: strike the nationalist counterrevolutionary, strike the scoundrel, strike him harder, don’t be afraid—and the activists, party men, young communists took up the cause in a Bolshevik fashion—then the collective farms took off the ground.”61 Khataevich had expressed a similar idea in 1933: “A ruthless struggle is going on between the peasantry and our regime. It is a struggle to the death. This year was a test of our strength and their endurance. It took a famine to show them who is master here. It has cost millions of lives, but the collective farm system is here to stay. We’ve won the war.”62

At the same conference, Balitsky, the head of the GPU in Ukraine, described the “debacle of the Ukrainian counterrevolutionary underground in 1933” as a result of a concerted GPU action in two directions: a) an attack against the grassroots anti-socialist groups in the countryside, infiltrated by kulak-Petliurite elements, and b) a decisive assault on the centers of counterrevolutionary leadership, the “Ukrainian Military Organization” and others, “which led insurgent, spying, diversionist work, and agricultural sabotage.” The GPU had also uncovered other Ukrainian nationalist parties, which Balitsky presented as an agency of “international counterrevolution, first of all, German and Polish fascism.”63 He could have mentioned his own role in the attacks on Skrypnyk, which drove the Commissar of Education to suicide on 7 July 1933. There was also the part played by the GPU in purging Skrypnyk’s Commissariat of Education of 200 employees in the central office, and removing all oblast directors and 90% of the raion heads.”64 Symptomatic of the intensification of the regime’s war against Ukrainian culture was the suicide in May 1933 of the writer Mykola Khvylovy.

At the end of 1933, the Stalin revolution from above came to a close in Ukraine, in the same way it began four years earlier, with a two-pronged attack on the Ukrainian farmers and the Ukrainian national elites, in sum, a genocidal assault on the Ukrainian nation.

---------------------------------------------

1 Special Report” of the Secret-Political Department of the OGPU (12 May 1934)..Sovetskaia derevnia glazami VChK-OGPU-NKVD, vol. 3, bk. 2, 1032-1934 (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2005), p. 572.

2 http://www.hrweb.org/legal/genocide.html

3 Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation — Analysis of Government — Proposals Redress. Washington, D.C., Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944

4 Prof. Raphael Lemkin, “Investigation of Soviet Genocide by U.N.”, The Ukrainian Weekly. 7 March, 1953.

5 “Ukrainians March in Protest Parade. 10,000 Here Mark Anniversary of the 1933 Famine — Clergy Join in the Procession,” The New York Times. 21 September 1933.

6 The Ukrainian Weekly, 26 September, 1933.

7 Raphael Lemkin Papers. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundatiion. Manuscripts & Archives Division. Lemkin’s text is posted on several internet sites in English and Ukrainian. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Journal of International Criminal Justice, 2009, N. 1. The text has appeared in Lubomyr Luciuk (ed.) Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932- 1933 in Soviet Ukraine. Kingston, Ont., The Kashtan Press, 2008. In that volume contains an article by Steven Jacobs, “Raphael Lemkin and the Holodomor: Was it Genocide?” Unfortunately, the author takes a curious “peasantist” approach, identifies the victims as “kulaks” (his emphasis) and wonders whether “the group in question” “meets Lemkin’s own criterion as a recipient group of the horrendous practices”? Jacobs thus misses the thrust of Lemkin’s analysis, which characterized the victims as a national group.

8 The sentence in Kosior’s speech reads: “At the present moment, the chief danger in Ukraine comes from local Ukrainian nationalism, in cahoots with the imperialist interest.” Izvestia 2 December 1933. P. 5.

9 Politycnyi terror I teoryzm v Ukraini XIX-XX st. Istorychni narysy. Kyiv, Naukova dumka, 2002. Pp. 278-281; 404-407.

10 Sovetskaia derevnia glazami OGPU-NKVD. T. 3, K. 1. 1930-1931. Moscow, ROSSPEN, 2003. P.p. 221-222.

11 Rozsekrechena pamiat’. Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini v dokumentakh GPU-NKVD. Kyiv, Stylos, 2007. Pp. 74-81. Quotations for the rest of the paragraph are taken from these pages..

12 Politychnyi terror I teroryzm v Ukrainie. P. 440.

13 Valerii Vasiliev and Lynne Viola, Kolektyvizatsiia i selianskyi opir na Ukraini (lystopad 1929-berezen 1930) (Vinnytsia, 1997), p. 195.

14 Holod 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini: prychyny ta naslidky Kyiv: Naukova dumka, 2003. pp. 421-22.

15 Sovetskaia derevnia, vol. 3, bk. 1, pp. 144-45.

16 Tragediia sovietskoi derevni: Kollektivizatsiia i raskulachivanie 1927-1939 gg: Dokumenty i materialy, vol. 2, Appendix no. 3.

17 See Tables in R. W. Davies and S. D. Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. Pp. 448, 467, 470. In terms of nutritive value, one million tons of grain was sufficient to feed five million people for one year.

18 Tragedia sovietskoi derevni, vol. 3, p. 318.

19 Holod 1932-1933 rokiv na Ukraini: ochyma istorykiv, movoiu dokumentiv (Kyiv: Nauka, 1990), p. 108. 20 Ibid., p. 148.

21 The complete letters are in Valerii Vasyliev and Yurii Shapoval, eds., Komandyry velykoho holodu: Poizdky V. Molotova i L. Kaganovycha v Ukrainu ta na Pivnichnyi Kavkaz, 1932-1933 rr. (Kyiv: Heneza, 2001), pp. 206-15.

22 R. W. Davies, Oleg Khlevniuk, et al.(eds). The Stalin-Kaganovich Correspondence, 1931-36, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 136-39. Underlined by Stalin. This is the only known acknowledgement of the Ukrainian famine by Stalin.

23 Holod, 1990. p. 186 (doc. 6.

24 Holod, p. 194. For details of the deliberations, see Komandyry velykoho holodu, pp. 152-64.

25 Tragediia sovietskoi derevni, vol. 3, p. 408. One letter writer takes apart the fallacious statements of Bernard Shaw and Sidney Webb (p. 409) Excerpts from other letters are on pp. 407-14.

26 Tragediia sovetskoi derevni, vol. 3, pp. 421, 443.

27 The Stalin-Kaganovich Correspondence, pp. 164-65.

28 Ibid., p. 169.

29 Tragediia sovietskoi derevni, vol. 3, pp. 453-54. The “Instructions on the Application of the Resolution of 7 August,” signed by the Chairman and the Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of the USSR and the Vice- Chairman of the OGPU, were sent to all republican and oblast authorities on 16 September 1932. In Tragediia sovietskoi derevni, vol. 3, pp. 477-79.

30 Stalin i Kaganovich Perepiska. Quotations in this and the following paragraphe taken from pp. 273- 274. Words underlined and doubly underlined by Stalin.

31 Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, pp. 356-360, 388-397.

32 Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, pp. 399-400.

33 Rozsekrechena pamiat: Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini v dokumentakh GPU-NKVD, comp. V. Borysenko, V. Danylenko, and S. Kokin (Kyiv: Stylos, 2007) p. 357.

34 Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, pp. 456-62.

35 Tragediia sovetskoi derevni, vol. 3, p. 530.

36 Davies and Wheatcroft, op. cit. p. 178.

37 Komandyry velykoho holodu, p. 49.

38 Ibid., p. 51.

39 Tragediia sovietskoi derevni, vol. 3, pp. 575-77; Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv na Ukraini, pp. 475-77.

40 The re-Russification of Ukraine attracted the attention of the Italian consulate in Kharkiv. "In government offices the Russian language is once again being used, in correspondence as well as in verbal dealings between employees." See "Italian Diplomatic and Consular Dispatches," Report to Congress. Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office. 1988. P. 446.

41 Genrikh Yagoda’s report to Stalin of 29 December 1932 is in Lubianka. Stalin i VChK-GPU-OGPU- NKVD. Ianvar 1922-dekabr 1936 (Moscow: Materik, 2003), p. 386.

42 Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, p. 530.

43 On Kaganovich’s trip to Ukraine, see Komandyry velykoho holodu, pp. 308-39.

44 Holod 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, pp. 495, 513, 521-22.

45 Komandyry velykoho holodu, pp. 324, 328.

46 Holod 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, p. 567.

47 Tragediia sovetskoi derevni, vol. 3, pp. 634-35. An English translation is in Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2001. Pp. 306-07. Balitsky had reported the departures of 31,693 farmers from Ukraine in December 1932 and the sale of 31,500 railway tickets for Russia in January 1933. See Lubianka, p. 394. 48 Sovetskaia derevnia, vol. 3, bk. 2, pp. 262-63.

49. Holod 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, p. 616.

50 Tragediia sovietskoi derevni, pp. 636-37. Sheboldaev added more precise details about the filtration points three days later. Ibid., p. 638.

51 A. Graziosi, "'Lettres de Kharkov': La famine en Ukraine et dans le Caucase du Nord à travers les rapports des diplomates italiens, 1932-1934," Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique XXX (102) 1989: 43. 52 Sovetskaia derevnia, vol. bk. 2, p. 263.

53 Ibid., p. 282.

54 Ibid., p. 354.

55 Holodomor 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, p. 619.

56 Tragediia sovetskoi derevni, p. 657.

57 Sovetskaia derevnia, vol. 3, bk. 2, pp. 524-25.

58 Ibid,. pp. 305-9.

59 Holod 1932-1933 rokiv v Ukraini, pp. 712-13.

60 Sovetskaia derevnia, vol. 3, bk. 2, pp. 351-52.

61 Pavel Postyshev, “Borotba KP(b)U za zdiisnennia leninskoi natsionalnoi polityky na Ukraini,” Chervonyi shliakh, nos. 2-3 (1934). http://www.archives.gov.ua/Sections/Famine/Postyshev.php

62 Victor Kravchenko, I Chose Freedom. New York, 1946. P. 130. Quoted by Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. London, Hutchinson, 1986. P.261.

63 V. Balitsky, “Vyshe bolshevistskuiu bditelnost i neprimerimost v borbe s klassovym vragom,” http://www.archives.gov.ua//Selections/Famine/Batytsky.php See also R. Conquest, Harvest of Sorrow, p. 219.

64 Yurii Shapoval and Vadym Zolotariov, Vsevolod Balytsky: osoba, chas, otochennia Kyiv: Stylos, 2002), p. 221.

No comments:

Post a Comment