In several essays at the

Gates of Vienna blog and

elsewhere I have dealt with the subject of genetic intelligence measured in IQ, inspired by Michael H. Hart’s groundbreaking and very politically incorrect biohistory book

Understanding Human History. Many people consider this topic to be “racist” and therefore taboo, but I will write about anything that I deem to be practically and scientifically relevant. On the other hand, there are quite a few things that IQ does not fully explain. We will look at a few of them here, related to geography, population density and level of urbanization. The single most important thing that IQ does not explain is why the scientific Revolution took place among Europeans, not among northeast Asians who have at least as high average IQ as whites. I will leave that issue for a separate essay.

Australia’s landmass of 7.6 million square kilometers is comparable in size to all mainland states in the USA minus Alaska, roughly eight million km2, but Australia has about 22 million inhabitants whereas the USA has over 300 millions. Both countries have similar histories in the sense that during the European colonial period, white settlers took over the land and built technologically sophisticated societies there, yet only one of them became a leading world power. This is because much of Australia and its water except for the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Queensland in the northeast is desert. The soil is poor and not nutritious. Most of the population is settled along the coast in the south and east, from Adelaide via Melbourne and Sydney to Brisbane. Simply put: Australia’s geology and ecology cannot sustain anywhere near the number of people we find in the USA. In this case, geology and geography matter a great deal. Australia is also located far away from major trading regions elsewhere. Thanks to modern transportation and communications technology, this drawback is less serious than it used to be, but it is still a significant factor shaping the country’s economic life.

At the other extreme,

Greenland, the world’s largest island, is more than half of the size of the USA at 2,175,600 km2, but with merely 57,000 or so inhabitants it has the lowest population density on Earth (excluding Antarctica, which is populated only by a few scientists) at 0.026 people per square kilometers. This is because cold and inhospitable Greenland is largely covered by ice and glaciers. By contrast, the most densely populated areas in the world are Macau in China and Monaco in Europe at 18,534 and 16,923 inhabitants/ km2, respectively.

Other geographical factors that are of great significance for the evolution of a society are waterways, navigable rivers and

access to the major oceans. No serious historian could ever properly write the histories of Britain or Japan without taking their island locations into account as a major factor in its own right. Several scholars have pointed out that the more rugged shape and topography of Europe compared to China is one of the reasons why China was unified politically earlier than Europe, an idea that deserves serious consideration. The Roman Empire at its height controlled only about half of Europe, not the far north and east.

Many events can best be explained by a combination of IQ and other factors. The Portuguese exploration of the African coast in the mid-1400s started the global Western European expansion. This exploration required a certain minimum IQ, which European nations had but sub-Saharan Africans did not have. This explains why Europeans travelled to Africa yet Nigerians didn’t discover Europe, but it does not explain why the Chinese didn’t explore the Atlantic, which they may have had the technological know-how to do if they wanted to.

The Europeans possessed a number of cultural and commercial push-and pull factors such as the drive to find new Christian converts and the desire to gain access to the lucrative spice trade of the Indian Ocean without Muslim middlemen. Asians did not possess a similar desire to go to Europe. Yet IQ does not predict which European nation would start this process. There is little reason to believe that the Portuguese had higher average IQ than the Poles, the Hungarians or the Finns. What Portugal did have was a favorable location next to the Atlantic Ocean and Africa which made it ideally situated to undertake long expeditions. All of the major European colonial powers were located in the far west, with access to the major oceans.

This does not mean that water access is an absolute necessity; Switzerland provides us with an important counterexample of a mountainous and completely landlocked country that has managed to create and sustain a very high economic, technological and scientific level. Nevertheless, sea access has normally constituted a considerable advantage. The only Eastern European country capable of projecting power far outside of Europe proper was Russia.

While many parts of Western Europe developed a dynamic and politically important population of urban traders, the lands in the eastern half of the continent suffered from less urbanization and more social restrictions, with less and less economic freedom the further east you moved toward Asia. These differences grew with the establishment of the Atlantic maritime economy and the Industrial Revolution. By the year 1700, the population in the whole of Eastern Europe was roughly equal to that of France alone; the only really significant urban markets in East-Central Europe were Constantinople, Vienna, Prague and Warsaw.

Chattel slavery within Europe was abolished in the post-Roman era, one of Christianity’s most positive contributions. Yet reality is not so simple that all those who were not slaves were free men who could carry arms and had freedom of movement. Serfdom at its most repressive constituted little more than modified slavery, and it intensified in Eastern Europe just as it declined in Western Europe. Capitalism, too, was a Western European invention.

The Middle Ages witnessed the rise of the specifically European, above all Western European, phenomenon of the semi-autonomous city, organized and known as commune. Stadtluft macht frei ran the medieval European dictum – city air makes one free. When the count of Flanders tried to reclaim a runaway serf whom he ran across in the market of Bruges, the bourgeois drove him out of the city. Cities consequently became poles of attraction and places of refuge. Migration to urban areas improved the income and status of the migrants and their families, but not their health. Cities were dirty and vulnerable to crowd diseases, European ones at least as much as some Asian cities. It was only in-migration that sustained the numbers of urban dwellers. Serf emancipation in Western Europe was directly linked to franchised villages and urban communes and to the density and proximity of these gateways.

Where cities and towns were few and less free, as was the case in much of Eastern Europe, serfdom persisted and worsened. Between 1400 and 1650, the social and legal conditions of peasants in the eastern half of Europe declined, as many free farmers lost their freedom. Russian, Polish and other lords seized more land for their own estates and demanded ever more unpaid serf labor. The daily life of peasants was hard everywhere, but the visibly harsher social conditions in the East were commented upon by Western European travelers.

The political power of peasants in Eastern Europe was weaker than in the West. Many serfs were bound to their lords in hereditary service and had to do much forced labor without pay. Russian serf families were regularly sold with or without land, and serfdom was abolished in Russia as late as in 1861. In Western Europe, free farmers and townsmen were the natural enemies of the landed aristocracy and would often support the crown in its struggles with local seigneurs. David S. Landes explains in The Wealth and Poverty of Nations:

“European rulers and enterprising lords who sought to grow revenues in this manner had to attract participants by the grant of franchises, freedoms, and privileges – in short, by making deals. They had to persuade them to come. (That was not the way in China, where rulers moved thousands and tens of thousands of human cattle and planted them on the soil, the better to grow things.) These exemptions from material burdens and grants of economic privilege, moreover, often led to political concessions and self-government. Here the initiative came from below, and this too was an essentially European pattern. Implicit in it was a sense of rights and contract – the right to negotiate as well as petition – with gains to the freedom and security of economic activity.”

City-states have been among the most dynamic entities in history, from ancient Mesopotamia and Greece to Renaissance Italy; their Achilles’ heel is that they are often too small to effectively defend themselves against aggression from larger political entities. They enjoyed greater success when they formed alliances, such as the medieval Hansa in northern Europe.

Science is first and foremost the creation of urban, literate cultures. Scandinavians produced the first significant scientific figures during the Renaissance period, and the likelihood of this happening was greatest in the region that was closest to the European mainstream and had the highest level of urbanization. This figure did emerge in the shape of the astronomer Tycho Brahe, who came from the Kingdom of Denmark, born in southern Sweden. With a roughly similar IQ and most other things being equal, the rate of excellence within the Nordic countries should be highest in Denmark and southern Sweden and slightly lower in more sparsely populated Norway and Finland. In the latter countries, it should be highest in urban regions such as the Helsinki area and the southwest coast of Finland and the Oslo Fjord region and partly Bergen in Norway. This hypothesis corresponds well with observed reality. For the same reason, many of the great accomplishments in Scotland took place in the densely populated Central Lowlands, which includes the cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee.

People with high intelligence need a chance to realize their potential, which they generally won’t have if they are uneducated farmers living at a near-subsistence level. Isaac Newton came from a family of English farmers, but his educated uncle recognized the boy’s talent and arranged for him to be sent to the university. Had it not been for this, Newton would not have been able to develop his theory of gravity. This illustrates the cluster effect: Individuals with great natural abilities need access to other people with high intelligence for intellectual stimulation, competition and exchange of ideas. A sheep herder sitting on an isolated mountain top with an IQ of 150 will no doubt be an extremely clever sheep herder, but not a world-class scientist. The cluster effect is slightly less important today than it was in the past since modern technology has made it easier to communicate with people in other places and countries without being physically close to them, but having access to a stimulating environment with intelligent people is still a tremendous advantage. Talent begets more talent.

Cities were not only where most of the significant figures worked, but also where many of them were born and raised. Obviously, they are important because many people live there, yet even if we adjust for population size and measure accomplishments per capita or per thousand individuals, cities still predominate over their rural surroundings. This does of course not imply that all large European cities were equally dynamic in all eras. Paris was far more dominant in French cultural life than any German city ever has been in German cultural life.

Germany has produced unusually many significant figures from scattered places, but cities were clearly relevant there as well. Cities attract both human and financial capital and often have a well-developed infrastructure of libraries and meeting places for exchanges of new ideas and impulses. They can be industrial, political or financial centers, but having a leading university or educational institution is particularly important for the rate of accomplishment.

According to Charles Murray’s modern classic Human Accomplishment, the Big Three in accomplishments are Britain, France and Germany, with Italy as number four. Significantly after the first four we find the region formerly known as Austro-Hungary plus Russia and the Netherlands, followed by Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Poland, the Balkans, Norway, Portugal and Finland. Britain, France, Germany and Italy combined account for 72 percent of all the significant figures in the arts and sciences from 1400-1950. If we break down the regions and cities, we find that great accomplishment was primarily concentrated in the European core, defined as Britain from the Scottish Lowlands with most of England and parts of Wales, southern Scandinavia, the northern and eastern regions of France including Paris, the Low Countries (Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Germany, parts of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and last, but not least, the northern half of the Italian Peninsula including Rome.

Certain regions stand out even within the Western European core, for instance Tuscany in northern Italy and southeast England in Britain. More than one hundred European cities or towns qualified for their own code in Human Accomplishment: In Austria, Graz and Salzburg made the list in addition to the capital Vienna. In present-day Belgium: Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Ghent, Ixelles, Jehay-Bodegnée, Liège, Louvain (Leuven), Namur, Saint-Amand and Tournai. In Britain and Ireland: Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Cambridge, Durham, Leeds, Liverpool, London, Manchester, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast and Dublin. In the Czech Republic, Prague and Brno; in Denmark, Copenhagen and Århus. In France: Besançon, Bordeaux, Grenoble, Le Havre, Lille, Lyon, Marseilles, Metz, Montpellier, Nancy, Paris, Rouen, Strasbourg, Tours and Valenciennes. In Finland, the capital Helsinki.

In Germany: Augsburg, Berlin, Bonn, Breslau (situated on the River Oder, currently known as Wrocław in south-western Poland), Cologne, Danzig (now Gdansk on the Baltic coast of northern Poland), Darmstadt, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt-am-Main, Freiberg, Göttingen, Halle, Hamburg, Königsberg (after World War II known as the Russian city of Kaliningrad), Leipzig, Lübeck, Magdeburg, Mannheim, Munich, Nuremberg, Stuttgart, Tübingen, Wittenberg and Würzburg. As examples such as Breslau, Danzig and Königsberg remind us, certain areas and cities have belonged to different countries at different times, following wars and the rising or declining fortunes of the various European nations. Germans exerted considerable cultural influence in East-Central Europe for many centuries. The southern coast of the Baltic Sea was a region of mixed Germanic, Slavic and Baltic influence; Copernicus probably spoke fluent German as well as Polish. Poland in turn went from being one of the largest states in Europe to non-existence as a political entity by the early nineteenth century.

In Greece we find Athens and in Hungary, Budapest. In Italy the most important cities were Bologna, Brescia, Cremona, Ferrara, Naples, Padua, Palermo, Parma, Piacenza, Pisa, Rome, Siena, Turin, Venice, Verona and Vicenza. The centers in sparsely populated Norway were the cities of Bergen and Oslo; in the very densely populated Netherlands they were Amsterdam, Delft, Haarlem, The Hague (Den Haag), Leiden, Rotterdam and Utrecht. In Poland, the previous capital city, Kraków and the present one, Warsaw. In Portugal, Lisbon. In the Russian Empire, Kiev (in the Ukraine), Moscow, Riga (the capital of Latvia), Saint Petersburg, Tallinn (the capital of Estonia), Vilnius (the capital of Lithuania) and finally Smolensk on the Dnieper River in far western Russia. In Sweden, Stockholm and the university town of Uppsala. In Spain: Barcelona, Cordoba, Granada, Madrid, Seville and Valladolid. Among the towns in dynamic Switzerland, Basel, Geneva and Zürich led the way.

The general level of education rose steadily in the Western world throughout the modern era. In Belgium and the Netherlands, the number of university students rose 3.5 times faster than the population from 1850-1900 and 8.6 times faster from 1900-1950. In France, the university population rose 48 times faster than the increase in population from 1900 to 1950. Urbanization has been one of the most pronounced hallmarks of industrial civilization, from the nineteenth until the early twenty-first century. There was a powerful trend of urbanization of the world’s population throughout the twentieth century which exceeded the rapid increase in the total global population. As of 2010 it has been projected that the majority of the world’s population, for the first time in the history of mankind, live in urban areas. At the same time, the number of university students has gone up sharply, both in absolute and in relative terms.

After 1950 the percentage of Western youths taking higher education continued to rise, especially from the 1960s, 70s and 80s onward when women joined in greater numbers, to the point of numerically dominating many university campuses. In short, the global number of urban, literate people with higher education has never been higher than after 1950, yet Charles Murray claims that the rate of great human accomplishment stagnated or declined during this same period. This means either that Murray is wrong in this regard or that the most recent increase in towns and higher education hasn’t paid off as well as the previous ones did.

Perhaps we had reached a point at the mid-twentieth century where most of the people with very high IQs in the West already took higher education, whereas those who joined later slightly lowered the average IQ of those with a university degree. Critics claim that too many people spend years of their lives at higher education, even those who do not strictly speaking need it. Society needs truck drivers, yet truck drivers do not normally need a master’s degree in English literature to be competent at their job. Another problem is the proliferation of Marxist groups in campuses. Many Western university students these days will come out with a warped and twisted view of the world and of their own civilization, which is not productive.

Also, while some major cities such as Berlin, Shanghai, Seoul or Tokyo have reached a high level of technological and economic sophistication, they are all predominately populated by high-IQ groups. By contrast, Mexico City is one of the largest cities on the planet, yet this fact hasn’t made Mexico a leading force in science or innovation. Nineteenth century London had poor and dirty quarters at the same time as it was arguably the most dynamic and innovative place in the world, but it is possible to argue that the growth of megacities in poorer countries in recent years has given rise to a new type of dysfunctional urban areas with massive slums.

May 19th, 2010 at 9:38 am

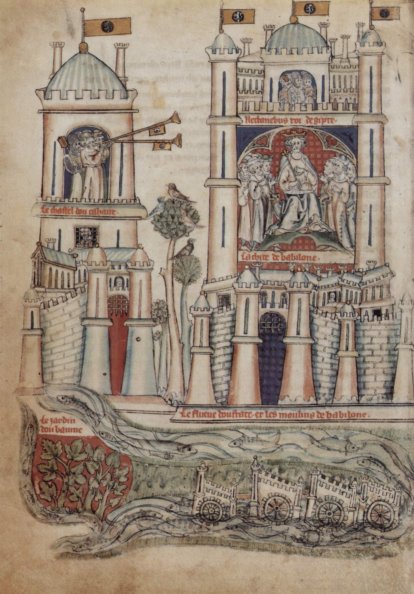

http://www.swisstraveling.com/2008/08/02/bellinzona/

May 19th, 2010 at 10:39 am

May 19th, 2010 at 12:41 pm

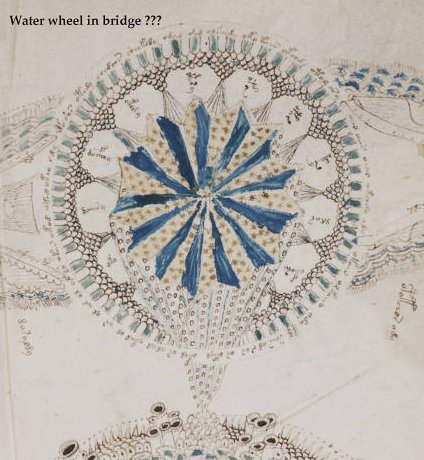

Unfortunately, I don’t have a date for this construction, but there are a number of walls with swallow tails facing the river.

There’s lake Garda with a few castles as well…

May 19th, 2010 at 1:17 pm

May 19th, 2010 at 1:48 pm

May 19th, 2010 at 4:03 pm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castelvecchio_Bridge

May 19th, 2010 at 4:14 pm

http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-30301837/stock-photo–the-scaliger-castle-in-sirmione-on-lake-garda.html

May 19th, 2010 at 4:21 pm

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Genova-Castello_d‘Albertis-DSCF5405.JPG

May 19th, 2010 at 4:33 pm

Paul: we’re long on swallowtails but short on seaside castle walls (or, as you point out, riverside castle walls or crenellated bridges).

May 19th, 2010 at 4:53 pm

http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://imgpe.trivago.com/uploadimages/52/32/5232406_l.jpeg&imgrefurl=http://www.trivago.it/angera-420556/castellorocca/rocca-borromeo-841341/foto-i5232406&usg=__iobI4sz9rw4UCD8IoXJEdxVFhiE=&h=320&w=480&sz=27&hl=en&start=21&sig2=CM0-_DHDAzB9XfMECV8QuA&um=1&itbs=1&tbnid=xyX1zSro8p7rnM:&tbnh=86&tbnw=129&prev=/images%3Fq%3D%2522Rocca%2BBorromeo%2522%26um%3D1%26hl%3Den%26safe%3Doff%26sa%3DN%26tbs%3Disch:1&ei=CBf0S6zAFs_Asgbxr42bDA