An interesting UFO case from medieval Spain

Antonio Huneeus | Dec 02, 2011

Inner wall of Ciudad Rodrigo

Years ago I received a package of Spanish UFO-related clippings and

documents and I was intrigued by one particular article titled, “Un OVNI

en el siglo XV” (A UFO in the 15th century). The story was not written

by an ufologist but by a literary editor, Luis Bonilla, in the magazine La Estafeta Literaria,

published by the prestigious cultural organization Ateneo de Madrid in

1978. It told the story a UFO sighting on January 5, 1433 in Ciudad

Rodrigo, seen by the entire court of King Juan (or John) II of Castile

(1405-1454), father of the famous Queen Isabella who backed Columbus.

The source of the account transcribed by Bonilla was a letter written by

a certain Bachelor Fernán Gómez de Cibdarreal, said to have been the

physician of the King, to the Royal Chaplain Pedro López de Miranda.

Although there is quite a bit of controversy concerning the authenticity

of this document, as discussed below, let’s see first its contents.

Fernán Gómez begins his letter to López de Miranda describing briefly

how the court had arrived to Ciudad Rodrigo (currently in the province

of Salamanca in western Spain) on its way to Madrid. The retinue

included a number of important figures like the Bishop of Palencia and

the Condestable (Constable) Don Alvaro de Luna, one of the era’s most powerful military leaders. The letter continues:

Medieval castle in Ciudad Rodrigo

I shall not tire your lordship with this narration, since we had just arrived [to Ciudad Rodrigo] when, walking on Wednesday the 5th of this month of January [1433], we suddenly saw a great flame of yellow fire attached to the sky move from one end to the other; it had inside like a black root and all its borders were more whitish than the middle; and it left with a great roar, causing horses and mules to ran in fear, and my own mule didn’t stop until it touched another mule. Great disputes about this arose between the learned ones and those with no degrees who, without having seen the words of Aristotle, talked about how this light was up there, and how its interior could be lit like a log. The dean of Burgos stated he believes it must be the matter from the first region [in the sky], viscous and condensed, lit by the Sun, and how its weight prevented its quick dispersal, and the nature of fire brought it from here to there while its viscous part was spent, and the roar was its end. I concur with his opinion, because it could not have been what Aristotle calls the nature of comets… because it would have not moved in such varied manner, nor any other, and it would have not ended with that roar. The enemies of the Condestable [Don Alvaro de Luna, Commander of the Army] said this flame was the Condestable, who would set ablaze Castile and the roar was his last gasp. These are fables as each one desires. We don’t know how is the earth beneath us, and we want to know how are the hidden places of the sky; and I think that Aristotle found something else in his century from what he says for sure in his writings. Our Lord, etc.

Title page of the apocryphal 1499 Burgos edition of the Centón Epistolario.

This is a remarkable letter in that it not only describes the

celestial phenomenon quite thoroughly, but adds fascinating

philosophical, scientific and sociological attempts to understand it

according to the limited knowledge available at the time. The fact that

the object made a big noise that scared all the horses and mules would

tend to rule out a meteor or a comet. The account is contained in the

“Epistle” (or Letter) LV (55) from a book entitled, CENTON EPISTOLARIO DEL BACHILLER FERNAN GOMEZ DE CIBDAREAL,

supposedly published in the city of Burgos in 1499. Centón is an old

Spanish word for a literary piece composed of another author’s phrases

and fragments, like a literary collage or pastiche. The Epistle or

Letter LVI (56), addressed to Juan de Mena (1411-1456), a well known

Spanish medieval poet, alludes to the same celestial event, although the

text was edited out to avoid repeating the same description. It reads:

The Printer to the Reader.

In this epistle the Bachelor of Cidareal narrates the same that was narrated previously to the first Chaplain of the King concerning the flame that showed itself in the sky, until the end of the narration, telling again the same event.

Your Lordship may have his say as someone who knows so much, and like that who puts his hands up to the elbows in the frame of Mercury.

Juan de Mena was the author of a remarkable allegorical poem entitled Laberinto de Fortuna

(Labyrinth of Fortune) full of mythological metaphors and hermetical

references, thus the phrase of “the frame of Mercury” and “someone who

knows so much.” The rest of the letter deals with political news like an

army of six hundred spears sent by the King of Castile to the border

with the Moorish Kingdom of Granada.

Page

with the 1433 UFO incident in Ciudad Rodrigo from the first edition of

the Centón Epistolario.

A controversial document

Unfortunately, as is often the case with UFO documents—even ancient

ones—there is quite a bit of controversy regarding the authenticity of

Fernán Gómez’s Centón. However, we are not talking of a modern

forgery but an old one going back to the 1600s, when this book was first

commented in Spanish literary circles. Back when I received the

original package it was very hard to research this kind of case. You had

to go to a public library or university library and find some reference

book, but surely not an original edition. Nowadays, using Google Books

or the massive site Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes,

which has a huge amount of resources for Spanish literary and

historical texts, one can easily find all the original editions and

commentaries with a little patience and skill.

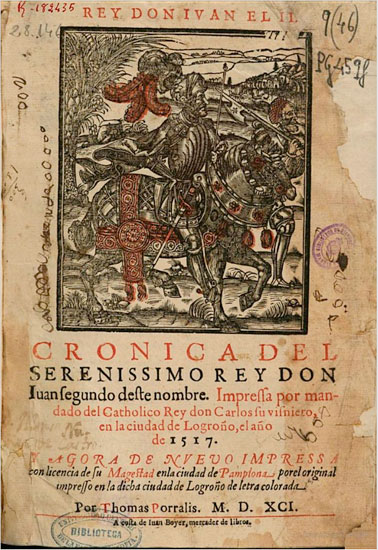

King Juan II of Castile in battle with all the royal insignias from an old Spanish manuscript.

Luis Bonilla alludes briefly to the controversy but cites a couple of

scholars who believed in the authenticity of the letters: Father Benito

Feijoo, an important encyclopedist author from the 18th century, and

Eugenio de Ochoa, a literary scholar from the 19th century, who

reprinted the Centón in 1850 in his Epistolario Español – Colección de Cartas de Españoles Ilustres Antiguos y Modernos (Spanish Epistolary – Collection of Letters from Illustrious Spaniards Ancient and Modern). In his Introduction, Ochoa wrote:

It is a fairly generalized opinion that the letters of the Bachelor Fernan Gomez de Cibdareal are forgeries and that its author is a made-up character that never existed, supported principally by the fact that there is no mention neither of him nor of his letters in our histories until very modern times; and that according to the consensus of bibliographers, the primitive edition of the Centón (Burgos, 1499) is notoriously apocryphal. Nevertheless, we cannot even agree with the hypothesis of a such fraud: its goal is not clear nor it seems credible that fiction would get so close to the truth up to that level. The Bachelor’s letters are a model of language and a treasure of curious news about the reign of Don Juan II . . .

Despite his eloquence, Ochoa seems to be definitely in the minority regarding the authenticity of the Centón.

Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, one of the towering figures of Spanish

literary scholarship in the 19th century, believed them to be a forgery

and so did the great majority of literary experts and historians,

particularly in modern times. Moreover, the probable culprit was already

identified as far back as the late 17th century. He was Juan Antonio de

Vera, Count of de la Roca (1583-1658), a diplomat and minor literary

figure in baroque Spain. He was a friend of the famous playwright Lope

de Vega and published a book under his own name, The Ambassador,

which had moderate success. Beginning in 1624, he served in several

diplomatic missions to the Holy See in Rome, the Kingdom of Savoy and

the Republic of Venice. But more germane to our subject, Spanish

historian Julio Caro Baroja stated that Vera suffered from a

“genealogical psychopathology,” which would explain his forgery of the Centón.

As it turns out, spliced here and there throughout the 105 alleged

letters of Fernán Gómez, there are references to the Vera family to pump

up their importance in early Spanish history.

A study by Carmen Fernández-Daza Alvarez of Madrid’s Complutense

University, “The Epistolary Centón of Juan Antonio de Vera,” published

in the Revista de Filología Románica, 1994-95, discusses all

the ins and outs of this affair. It even includes a mention of “a full

epistle debating certain cosmetological phenomena that Aristotle had

studied and that didn’t seem similar to the balls of fire they had

seen.” Fernández-Daza also sketched what she believes to be the way

Count of de la Roca forged the 1499 apocryphal edition of the Centón. The Count was the Spanish Ambassador to the Republic of Venice in the 1630s and, according to Fernández-Daza,

Tomb of King Juan II of Castile in Burgos.

The Spanish Embassy in Venice had a clandestine printing press organized by Count of de la Roca, to which types bought in Germany arrived often. There he indulged with gusto in his falsifications, supporting the provocations and responses of Italian authors and paying for chimeric editions. Sometimes he printed in Trieste books which were said to have been edited in Orleans. It is almost certain that the Centón was printed in that Venetian “stamperia” [printing press] between the years of 1636 and 1640 and Spain received it full of Italianisms.

The real UFO of 1433

All the experts who questioned the authenticity of the Centón

also agreed that, for the most part, the Count of de la Vera utilized

real events during the reign of King Juan II to compile the letters of

his supposed physician. The main source for this material was the Chronicle of Juan II

of Castile, a massive chronological history of his reign beginning with

his childhood in 1406 up to his death in 1454, which was compiled and

edited by several authors including Alvar García de Santa María and

Fernán Pérez de Guzmán.

Title

page of the Chronicle of King Juan II from a 1591 Pamplona edition.

This book was printed several times in the 16th century, including

its first edition of 1517 printed in Logroño, which the Library of

Congress calls “one of the masterpieces of early Spanish printing.” Its

full title is Cronica del serenisssimo Rey Don Juan Segundo deste nombre (Chronicle of the Most Serene King Don Juan the Second of this name). Unlike the Centón,

there is no doubt whatsoever about the authenticity of this book. If we

turn to the Table of Contents for “the year of thirty three” (1433), we

see Chapter ccxxxvi (236), “Of how when the King left Ciudad Rodrigo, a

great flame appeared in the sky, which lasted a long time, and which

all that saw it were marveled.” The full text of Chapter 236 dealing

with this event is the following:

While the King was in Ciudad Rodrigo, he decided to call the procurators, ordering that they should come to the town of Madrid, and he left from Ciudad Rodrigo at the beginning of the year of one thousand and four hundred and thirty three years, on Wednesday on the fifth day of January, and as they marched they all saw a great flame that was running in the sky, which lasted a long while, and which gave such a big roar that was heard up to seven or eight leagues from there. The King continued his march to Madrid . . .

This text clearly confirms that some unusual celestial object was

seen in the sky sometime during the day on January 5, 1433. The report

adds that the phenomenon lasted for a long while and was followed by a

loud roar. The old Spanish league is a unit of measurement roughly

equivalent to about 4.2 km or 2.6 miles, which means the UFO roar was

heard from a distance of about 16 miles. This was obviously the original

text from which the Count of de la Roca added a couple of colorful

details like the horses and mules running in fear and all the talk about

Aristotle and the viscous matter from the first region of the sky,

etc., stuff that a cultivated literary man like Juan Antonio de Vera

could have added easily. But the basic report is still valid.

A weird Fortean phenomenon in 1438

The old medieval town of Maderuelo

When the King was in Roa in that year [1438], he was told how in Maderuelo, a town of the Condestable [Don Alvaro de Luna], a marvelous thing occurred which has never been seen nor heard in the world: which was that they saw coming from the air very large stones, like light sparrows, which didn’t weight more than a feather, and even though some of them hit the heads they didn’t cause any damage: and these fell in very large numbers over that town and near it, and because the King and all those who heard of it had doubts, he sent the Bachelor Juan Ruyz de Agreda, a military officer of his court, to go there to inquire if this was true: and he went, and not only certified that these were seen, but he brought some of those stones, as large as a small pillow and as light as a feather, and they were all hollow and floxas, so that the King and all those who saw them were totally marveled.

I was unable to find the meaning of the old Spanish word floxas; another old word used in the text, tova,

also gave me some trouble, as it was not mentioned in any modern

Spanish dictionary, though the Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy

identified it as a cogujada, a type of bird of the same family

than the sparrow. The old medieval town of Maderuelo is located in the

province of Segovia in Castile. As for the cause of this event, I can’t

find no explanation whatsoever, but it seemed important enough for King

Juan II to send a high ranking military officer of his court (the old

Spanish word is adalid, a military leader) to investigate and

bring back some of the stones that fell from the air . Strange things

were going on in Castile in the 1430s indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment