The UFO Events at Minot AFB (one of the best cases ever)

A Narrative of UFO Events at Minot AFB

PART 6

Thomas Tulien

Investigation of UFO Events at Minot AFB

on 24 October 1968

Following the UFO events, Strategic Air Command, Offutt AFB, NE, initiated investigations. After the B-52 landed, the pilot Maj. James Partin reported to Base Operations for a debriefing. Minot AFB investigating officer, Lt. Col. Arthur Werlich, was awakened and informed of the situation. Later, the 5th Bombardment Wing commander requested an analysis of the B-52 radarscope film by targeting studies officer SSgt. Richard Clark. The 810th Strategic Aerospace Division commander, Brig. Gen. Ralph Holland, debriefed the B-52 crewmembers. The 91st Strategic Missile Wing commander sent a team to investigate the break-in at Oscar-7. Werlich phoned SAC headquarters requesting technical assistance for his investigation. Denied assistance, he was instructed to comply with Air Force Regulation 80-17.

Later in the day, Werlich phoned Project Blue Book at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, reporting the UFO events, and began the process of collating the case data per AFR 80-17. Several days later, he submitted the Basic Reporting Data, and following, Blue Book staff requested supplemental information. Werlich also forwarded all information to Gen. Hollingsworth at SAC headquarters for briefing Commanders and staff.

In the week following, Air Force officers arrived from off base to review the radarscope film and invited B-52 Navigator Capt. Patrick McCaslin to join the meeting. Oscar-Flight Security Controller SSgt. William Smith informed Werlich of numerous reports of unusual lights near the Canadian border, and recalls an officer spent a few days around Oscar-2 camped in a vehicle. Blue Book chief Lt. Col. Hector Quintanilla evaluated the case data received from Minot AFB, and submitted a final case report on 13 November 1968.[1]

-----------------------

Investigation of UFO Events at Minot AFB

on 24 October 1968

Thomas Tulien

1. Background

The modern

UFO era was ushered in on the afternoon of 24 June 1947, when private pilot

Kenneth Arnold reported nine, silvery crescent-shaped discs traveling at high-speed

near Mt. Rainier, Washington. Based on Arnold’s description, headline writers

coined the phrase “flying saucers” for the new phenomenon, heralding the story

in newspapers across the country. The repercussions encouraged other citizens

to come forward with their own reports of puzzling things seen in the sky — many

before Arnold’s account.

The considerable increase in sightings over the first week of July

1947 brought the first official statements in the press. On 4 July, the New York Times quoted a

spokesman as stating the Air Force is “inclined to believe either that the

observers just imagined they saw something, or that there is some

meteorological explanation for the phenomenon.” Evidently, officials assumed

that flying saucers were merely some sort of transitory phenomenon and would

soon go away.

The

situation took an alarming turn on 8 July, when Air Force pilots, other

officers, and a crew of technicians at a high-security research and development

facility in the Mojave desert, observed reflecting, silver-colored “flying

discs” traveling at high-speed against prevailing winds. All attested that they

could not have been airplanes. Pentagon officials suddenly wanted answers,

issuing orders for Air Force Intelligence to investigate all reports.

By August,

analysts had concluded that the phenomenon was real, and of a disk-like aerial

technology with very high-performance characteristics. For purposes of analysis

and evaluation, it was assumed that the flying saucers were manned aircraft of

Russian origin.[2]

In January 1948, USAF headquarters established Project Sign with the directive,

“to collect, collate, evaluate, and distribute to interested government

agencies all information concerning sightings and phenomena in the atmosphere

which can be construed to be of concern to the national security.”

Project

Sign investigated several dozen sighting reports from credible observers that

they could not explain, and considering the performance characteristics and

inconceivable power plant requirements; possibly nuclear — or even more exotic — it

was impossible they could be ours, or even the Soviets. In September 1948, they

drafted a formal intelligence summary, or “estimate of the situation,”

concluding that the flying objects were interplanetary spacecraft.

The estimate made its way up into the higher echelons of the Air Force, but

when it reached all the way to Chief of Staff General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, it

was “batted back down” without his approval. The conclusion lacked proof.

In February

1949, Sign issued its report qualifying the project as “still largely

characterized by the collection of data.” On the other hand, “proof of

non-existence is equally impossible to obtain unless a reasonable and

convincing explanation is determined for each incident,” acknowledging that the

lack of data in reports by qualified and reliable witnesses “prevents definite

conclusions being drawn.”

Unable to

easily resolve the issue, and disengage itself from the public side of the

controversy, Air Force policy shifted to downplay the significance and

effectively put an end to UFO reports. Project Sign staff, and top people in

the intelligence division, were transferred or reassigned. The project was even

given a new name — Project Grudge. New staff operated on the premise that all

reports could be conventionally explained, however, throughout 1950 attempts to

terminate the project proved ineffective.

Senior air traffic controller for the Civil Aeronautics Administration,

Harry G. Barnes, tracked some of the UFOs that were reported over

Washington, D.C. in July 1952. In a widely distributed newspaper

account, he wrote: “There is no other conclusion I can reach but that

for six hours on the morning of the 20th of July there were at least 10

unidentifiable objects moving above Washington. They were not ordinary

aircraft. Nor in my opinion could any natural phenomena account for

these spots on our radar. Exactly what they are, I don’t know.” The Air

Force explained the cause of the reports as anomalous radar propagation

due to temperature inversions. (Photo: Time-Life Books Inc.) The full text of the article is available here.

The one

uncontrollable variable — UFO sightings — refused to go away. As Cold War tensions

escalated with the Soviet Union, Air Force commands responsible for the air

defense of the North American continent were continuing to experience

unexplained UFO incidents, and justifiably concerned, if not perturbed, about

the way the Pentagon was handling intelligence on these matters. USAF, Director

of Intelligence General Charles Cabell agreed, ordering an immediate

reorganization of the project.

Under the leadership of Captain Edward J. Ruppelt, new staff

designed and instituted plans for a systematic study of the UFO phenomenon. In

March 1952, the project received a new name, Project Blue Book, and formal

authority promulgated by Air Force Letter 200-5. Reports were on a dramatic

increase nationwide, culminating over two consecutive weekends in late July,

when radar systems tracked UFOs cavorting in high-security areas above

Washington, D.C.

On Saturday

19 July, at 11:40 p.m., a group of unidentified flying objects appeared on the

long-range radarscopes in the Air Route Traffic Control (ARTC) center, and the

control tower radarscopes at Washington National Airport. The objects moved

slowly at first, and then shot away at fantastic speeds. Several times targets

passed close to commercial airliners, and on two occasions, pilots reported

lights they could not identify that corresponded to radar returns at ARTC.

Captain S.C. "Casey" Pierman, a pilot with 17 years of experience,

was flying between Herndon and Martinsburg, W.Va., when he observed six bright

lights that streaked across the sky at tremendous speed. "They were,"

he said, "like falling stars without tails.”

The

following weekend, Washington National Airport and nearby Andrews AFB,

Maryland, radar picked up as many as a dozen unidentified targets. This time,

Air Defense Command scrambled F-94 jet fighter-interceptors from New Castle

AFB, Delaware, resulting in what one pilot described as an “aerial cat and

mouse game.” When the F-94s arrived in the area the UFOs would disappear, and

when they left the UFOs reappeared.[3]

The front page of the Washington Post on July 28, 1952. The full text of the article is available here.

On Monday

morning, the front pages across America heralded the story of UFOs outrunning

fighter planes. In Iowa, the headline in the Cedar Rapids Gazette read like

something out of a sci-fi flick: “SAUCERS SWARM OVER CAPITAL.” An unidentified

Air Force source told reporters “We have no evidence they are flying saucers;

conversely we have no evidence they are not flying saucers. We don't know what

they are.” Responding to banner headlines and public

alarm, President Truman ordered the Director of Central Intelligence, General

Walter Bedell Smith, to look into the matter.

General

Smith assigned a special study group in the Office of Scientific Intelligence

(OSI), anchored by Assistant Director of Scientific Intelligence, Dr. H.

Marshall Chadwell. The group was to focus on the national security implications

of UFOs, and the CIA’s statutory responsibility to coordinate the intelligence

effort required to solve the problem.

In August

and September, OSI consulted with some of the country’s most prominent

scientists. Chadwell’s tentative conclusions addressed national security

issues, recommending psychological-warfare studies and a national policy on how

to present the issue to the public. He also acknowledged the air vulnerability

issue, and the need for improved procedures for rapid identification of unknown

air traffic — a vital concern of many at the time, since the U.S. had no early

warning system against a surprise attack.

Furthermore,

Chadwell briefed Gen. Smith on 2 December, convinced “something was going on

that must have immediate attention.”

Sightings of unexplained objects at great altitudes and traveling at high speeds in the vicinity of major U.S. defense installations are of such nature that they are not attributable to natural phenomena or known types of aerial vehicles.

He recommended an ad hoc committee be formed to “convince the

responsible authorities in the community that immediate research and

development on this subject must be undertaken,” with an expectation that this

would lead to a National Security Council, Intelligence Directive for a

prioritized project to study UFOs. What he got was something quite different.

In January

1953, the CIA convened a panel of prominent scientists, chaired by Caltech

physicist and defense consultant Dr. Howard P. Robertson, in order “to evaluate

any possible threat to national security posed by Unidentified Flying Objects

and to make recommendations thereon.” After four days, the panel concluded that

the evidence presented shows no indication that UFOs constitute a direct threat

to national security, however, continued emphasis on UFO reporting does “in

these parlous times,” threaten the orderly functioning of the government, while

cultivating a “morbid national psychology in which propaganda could induce

hysterical behavior and distrust of duly constituted authority.” A clearly

defined approach to the problem was established. The Robertson panel

recommended that the national security agencies debunk UFO reports and

institute policies of public education designed to reassure the public of the

lack of evidence (and “inimical forces”) behind the UFO phenomenon.[4]

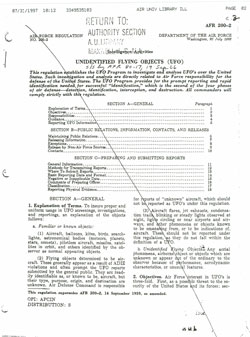

Air Force Regulation 200-2

In response

to the Robertson panel recommendations, USAF headquarters promulgated Air Force

Regulation 200-2 on 26 August 1953, codifying the official UFO policy chiefly

as a public relations issue.[5]

Indeed, a 1959 revision was unequivocal in declaring that, “Air Force

activities must reduce the percentage of unidentifieds to the minimum” (AFR

200-2, par. 2c).

To achieve

this, air base Commanders were responsible for “all investigative action

necessary to submit a complete initial report of a UFO sighting,” and

instructed to make every effort “to resolve the sighting in the initial

investigation” (par. 3b). Further, “all Air Force activities will conduct

investigations to the extent necessary for their required reporting action (see

paragraphs 14, 15 and 16).” This amounted to collating a formatted list of

Basic Reporting Data and transmitting it to Blue Book; with the caveat, “no

activity should carry an investigation beyond this point” without first

obtaining verbal authority from Blue Book at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio (par.

5).

Thus, Air

Force investigators were explicitly limited to compiling responses to a

formatted list of questions prescribed by AFR 200-2 (par. 14), and restricted

from conducting any full-scale investigations and gathering all the available

data. Blue Book was relieved of any investigative burden. If the UFO report

remained unidentified at the base level, it was their responsibility to simply

evaluate the data it received and submit a final case report.

In order to

“reduce the percentage of unidentifieds to the minimum,” Blue Book adopted the

premise that all UFO reports result from either hoaxes, or the

misidentification of a natural object or phenomenon. They broadened the

identified category to include possible and probable

explanations, allowing investigators to identify a report based on the

probability that a sighting was of a known phenomenon. In press

releases, and year-end Blue Book evaluation statistics, the possible and

probable subcategories simply disappeared and the sightings were listed

as identified.[6]

To control

the flow of information to the public and media, Blue Book forwarded a copy of

the final case report to the Secretary of the Air Force, Office of Information,

which was solely responsible for “release to the public or unofficial persons

or organizations all information or releases concerning UFO’s, regardless of

origin and nature” (par. 7). The only exception being “in response to local

inquiries regarding any UFO reported in the vicinity of an Air Force base, when

“the commander of the base concerned may release information to the press or

general public only after positive identification of the sighting as a familiar

or known object” (par. 8).

The policy

effectively institutionalized secrecy. To further ward off publicity leaks, in

December 1953, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued Joint-Army-Navy-Air

Force-Publication-146 (JANAP-146), which made releasing any information about a

UFO report to the public, a crime under the Espionage Act. Only if Blue Book

could positively identify the sighting as a hoax or misidentification would the

Air Force release the information to the public. These policies remained in

effect through 17 December 1969, when the Air Force announced the termination

of Project Blue Book.[7]

-------------------------------------

Investigation of UFO Events at Minot AFB

on 24 October 1968

Thomas Tulien

2. Strategic Air Command Investigations

Certainly, Strategic Air Command Commanders and

staff understood the objectives of the Air Force UFO policy. Moreover, strict

compliance with the regulation was mandatory, even to the extent of managing

information that would not facilitate the policy and support a conventional

explanation.

On 24 October, following the landing of the B-52,

Commanders at Minot AFB ordered immediate debriefings and investigations. These

inquiries occurred before notifying Project Blue Book of the UFO events late in

the afternoon, while the results were not available to Blue Book investigators.

Over the next two weeks, officials at SAC headquarters monitored the progress

of the Blue Book investigation, and Minot AFB investigating officer, Lt.

Colonel Arthur Werlich, forwarded all the information he collated to General

Hollingsworth for briefing SAC’s Vice Commander in Chief, Lt. Gen. Keith Compton.[8]

B-52 Pilot Debriefing

Following 4:21 a.m. (CDT), at the time of the B-52

pilots observation and overflight of the UFO on or near the ground, controllers

at Radar Approach Control (RAPCON) relayed the following request to the pilots:

“JAG 31 (garbled) requests that somebody from your aircraft stop in at baseops

after you land.”[9]

Apparently, somebody in command wanted to know what

the B-52 pilots had experienced, though the purpose of the debriefing and the

officials in attendance are unknown. Most likely, the request came from Minot

AFB Commander Col. Ralph Kirchoff, who was responsible under AFR 80-17 for

providing the investigative capability necessary to submit a complete initial

report of a UFO sighting.[10]

The senior officer who reported to Base Operations was the non-crew pilot Major

James Partin. Meanwhile, the B-52 crewmembers proceeded to the routine

post-flight mechanical debriefing before eventually heading home to bed.[11]

At some point, they received an order to return later in the morning for a

debriefing in the office of the commander of the 810th Strategic

Aerospace Division, Brig. General Ralph T. Holland.[12]

B-52 Radarscope Film Analysis

At 7:30 a.m., 5th Bombardment Wing

intelligence officer Staff Sergeant Richard Clark arrived for work at the headquarters

building, and was directed to set aside routine duties in order to analyze the

B-52 radarscope film. In a 2003 interview he recalls:

CLARK: Our major priority was keeping up with the intelligence of the day — we were virtually always updating the bombing information for what we were going to do if we came to war over Russia…. But this turned into a priority so we informed the photo lab that we wanted it now. [13]

The primary concern was to determine whether the

film confirmed the account of the B-52 crewmembers, though, Clark recalls “the

big question was how fast it was going and what we felt it was.” He retrieved

the processed film from the photo lab, and based on the sequence illustrated by

the 14-radarscope photographs, recalls estimating a minimal average speed of

the UFO at 3900 mph.[14]

By early afternoon, he had completed his report

confirming the account of the B-52 crewmembers, while concluding that the speed

and maneuverability of the UFO were phenomenal. He requested two sets of 8 X 10 positive prints of the

significant 14 radarscope film frames, one to include in his report sent up his

chain of command, while retaining the other as a personal desk-copy.[15]

Like B-52 Navigator Capt. Patrick McCaslin, what

impressed Clark were the speed and performance characteristics of the UFO:

CLARK: Well, it had to have been a UFO. We had nothing that could do the kind of speed it had back then and be able to change directions. I mean, flying with the plane and changing directions while still maintaining — you’re going like this [indicating straight line motion with hand] and then all of a sudden it’s over here, and it’s still going this way. Even if we had something that could go that fast it’s going to go that fast this way — but it can’t go that way too. That’s why it was phenomenal. It had to be something other than what we were aware of, you know, I did not think our technology had anything like that as far as capability — so it’s got to be a UFO.[16]

Furthermore, someone

informed SSgt. Clark

That they were sending somebody out from Washington to talk to the crew. I do not remember who asked me, but they wanted to know if I was sure about this [pointing to the radarscope photos], and I told them, ‘it’s there in black and white, there’s nothing else that it can be.’[17]

B-52 Crew Debriefing

Later that morning, the B-52 crewmembers returned to

base for a debriefing in the office of the commander of the 810th

Strategic Aerospace Division. At the time, Brig. General Ralph Holland was the

highest-ranking officer stationed at Minot.[18]

In attendance were Co-pilot, Captain Bradford Runyon; Radar Navigator, Major

Charles Richey; Navigator, Capt. Patrick McCaslin; Electronic Warfare Officer

(EWO), Capt. Thomas Goduto; and Gunner, Technical Sergeant Arlie Judd. Not

present at the debriefing were Maj. Partin, the B-52 instructor pilot from

another crew who was onboard this mission being evaluated to maintain ratings

by Aircraft Commander, Capt. Don Cagle; nor Cagle, who had intentionally

avoided any direct involvement in the UFO events.[19]

For the first time the crewmembers learned of the

extent of the ground observations and missile site intrusions. Unfortunately,

it is doubtful that just a few hours after the events, Gen. Holland — or even

Colonel B.H. Davidson, the 91st Strategic Missile Wing commander who

briefed Holland on the situation — would have had a complete grasp of the

situation. As a result, information provided to the crew by Holland may have

been inaccurate or misconstrued. In particular, the recollections are not supported

by the existing documentation.

For example, following are pertinent recollections

of Capt. Runyon regarding the debriefing.

RUNYON: Well instead of asking us any questions, he just informed us as to what had gone on during the previous night, about outer and inner alarms going off at one of the missile sites. He did mention that there had been two different instances having to do with missiles within a week, one at another base — and I couldn’t differentiate the things that were going on from one opposed to the other. There had been outer and inner alarms activated and Air Police [Security Alert Team] had been sent to investigate. The first Air Police had not reported in. Other Air Police were sent to check and found the first Air Police either unconscious or regaining consciousness, and the paint was burned off the top of the vehicle. The last they remembered is that something was starting to sit down on them — and they started running. The Air Police did go onto the missile site and the 20-ton concrete blast door — he might have called it blast door — anyway, the 20-ton concrete lid had been moved from the top of one of our Minuteman missiles, and the inner alarm had been activated. He also mentioned that Air Police had seen us fly over, and had seen the object take off and join up with us. Basically that was it. I think that he asked us for any additional input. I don’t remember whether I mentioned anything or not.

INTERVIEWER: You never described the object you overflew?

RUNYON: I don’t think I ever did. Maybe to some of my friends in Stanboard, or to my crew when they asked about it. Maybe they thought I never looked outside the airplane; I have no idea why I was ignored.[20]

Capt. McCaslin recalled less detail, however the essential experience of the Security Alert Team (Air Policemen) is similar.

INTERVIEWER: Do you recall other topics of discussion?

MCCASLIN: No, not really. I remember he volunteered the information about the Air Policemen. He volunteered the information about the missile alarms going off. I’m sure he talked about other things, I just don’t remember — those are the things that stick in my mind …. My memory is that General Holland said that there were two — and he was saying it like he was very sympathetic toward these two Air Policemen. You know, like, imagine being in this position — that at the time our aircraft did the low approach there were two poor Air Policemen out there with this thing hovering, or something hovering directly over their pickup truck. I think he said they were responding to one of the missile alerts that had gone on in the missile —

INTERVIEWER: Alarms?

MCCASLIN: Yeah. And there may have been more that responded, but they were either the team — the Air Policemen responding, or one of the crews of Air Policemen responding, and that this thing was directly over their vehicle.

INTERVIEWER: Did it damage the vehicle in any way?

MCCASLIN: Don’t know if he told us that. The only memory I have is that it was lit in some fashion when it was over the top of them, and my impression is that it was very close to their vehicle, and that they were scared to death. And at the point these Air Policemen saw our aircraft taking off or doing a low approach — they didn’t know which — at the base, my impression is it was off to their left, that this thing went dark and began to climb in the direction of our aircraft.[21]

The impression is that the crewmembers were

struggling to incorporate the information related by Holland with their own

experience, in order to create a coherent picture of the events. It is unclear,

however, whether Holland’s information describes additional undocumented events

at other missile Launch Facilities, or was misconstrued from the facts.

For example, when the

missile maintenance team of Airman (A1C) Robert O’Connor and A1C Lloyd Isley

arrived at the N-7 Launch Facility around 3:00 a.m., they reported the UFO

circling to the south to SSgt. James Bond at the November-Launch Control

Facility. November-Security Alert Team member A1C Joseph Jablonski recalls

O’Connor’s hysteric-sounding voice over

the radio as he was apparently describing the bright object hovering directly over them at the N-7.[22]

Later, when the personnel at N-7 (by this time including Jablonski and Adams)

observed the incoming B-52 in the west, the UFO they had been observing for

over an hour in the southeast disappeared, which could be construed as, the UFO

“went dark … at the same time they saw our airplane.” For example:

McCASLIN: My memory is that it was at that briefing where I learned that they saw that thing leave them … my memory is that he said that it went dark — it was hovering over them — went dark and lifted up. And, at the same time they saw our airplane making that initial approach it took off in the same direction our airplane was going.[23]

McCaslin assumes this occurred during their initial

approach to the runway before flying out

to the WT fix, which is also when RAPCON requested they look out for “any

orange glows out there.” In other words, the UFO described by Holland as

brightly lit while hovering over the top of a security vehicle, suddenly “went

dark,” and followed the B-52 up to altitude in the northwest where it first

appeared on radar. According to the existing documentation, this could not have

been the UFO observed by personnel at N-7, or have occurred at the Oscar-7,

since the break-in was after the terminal landing of the B-52.

This suggests that there were additional

undocumented UFO events at other missile Launch Facilities. For example, Runyon

recalls that Gen. Holland “did mention there had been two different instances

having to do with missiles within a week — one at another base.” This confused

Runyon, since he could not “differentiate the things that were going on from

one [event as] opposed to the other.” In addition, Richard Clark recalls hearing

about alarms at three missile sites, and alludes to the experience of the

missile security personnel as recalled by the crewmembers:

CLARK: I don’t know how accurate it is, and I can’t remember whom I heard it from but it had to be somebody in the wing. I heard they sent a crew out to one of the missile silos after the alarms went off and that something similar to that happened to the crew, you know, the motor stopped, the lights went off — but I cannot remember. I don’t even remember which three silos went off.

INTERVIEWER: Three silos?

CLARK: Three separate silos went off, and they ended up — what I did hear was that they could not find anything. Nobody could have been in there.[24]

Capt. Goduto also recalled a

discussion about security intrusions at three missile sites:

GODUTO: I can’t remember, it could have been a discussion at a later time when they said there were possibly three intrusion alarms that had gone off at the missile silo sites. This would have been the same evening, right at the time when things were occurring …. Security [Alert] Teams responded but they found no locks, or no entries there.[25]

In any event, the consensus of the B-52 crewmembers

was that the debriefing seemed perfunctory, and not concerned with effectively

interrogating them to obtain useful information regarding the events or their

particular experiences. Goduto felt “the right questions weren’t asked by the

interviewers,” while Arlie Judd assumed the debriefing was merely pro forma “in

case somebody happened to ask them.”[26]

Moreover, during the Blue Book investigation, none of the B-52 crewmembers were

interviewed, nor completed an AF-117 Sighting of Unidentified Phenomena

Questionnaire regarding their experience.

Oscar-7 Launch Facility Break-In

At 4:49 a.m., nine minutes after the B-52 landed,

Oscar-7 Outer-zone (OZ) and Inner-zone (IZ) security alarms sounded underground

in the Oscar-Launch Control Center. It was not unusual for the sensitive

perimeter alarm system to activate because of animal activity, equipment malfunctions,

and even drifting snow; however, the triggering mechanisms for the inner-zone

alarms were isolated from the local environment, and both alarm zones

activating at the same time was an exceedingly unusual situation. Oscar-Flight

Security Controller, Staff Sergeant William Smith Jr., immediately dispatched

his Security Alert Team of A1 Donald Bajgiar and A1C Vennedall to O-7.

Oscar-7 Launch Facility located 24 miles north of

Minot AFB, looking south-southeast; and (inset) the weather cover has

been raised and the vault door removed, providing access to controls for

opening the large primary door (A-plug) to gain access to the missile

silo. In this instance, the weather cover had been raised and the

combination dial turned off its setting, thus triggering the IZ alarm.

When the team arrived, they found the front gate

unlocked and open, while a weather cover protecting the controls for access to

the missile silo was left standing open. Inside, somebody had turned the

combination lock dial on the vault door off its setting, thus triggering the

inner-zone alarm. The security team conducted a procedural investigation of the

site but found no additional evidence of intruders.[27]

Later the same day, SSgt. Smith met another team sent out by the 91st

Strategic Missile Wing headquarters to conduct a further investigation at O-7.

SMITH: I was still on duty the next day. I think it was a maintenance Lieutenant that came and was doing the investigation, so I went out as well to let them know that this is strange because we had never in my experience found a gate wide open with those locks that we had — unless you had a key. The lock was not broken. We just knew we had somebody on that site with all the weird things going on. So we did go through the process of investigating the site, but that gate being open, we were not happy with that. In fact, I think that's why they sent somebody out, and they did find radiation on part of the site that was away from the missile — on the parking area. You had the missile and you had a service area right next to it. We had keys to get down inside and check it out.

INTERVIEWER: Right, the support equipment.

SMITH: Yes, when I was working as an inspector I used to hide down there from the guys and scare the doo-doo out of them under the sub floor and things like that. Well, we went through that whole process, and I was with my crew when they did that — as supervisor I decided that I needed to go out there and find out what's going on. I stayed with the crew, which I did not have to being in charge of security. Anyway, that is how I knew what went on. When the Lieutenant was out there, they did find a circular ring of low-grade radiation, and he called it low grade such that it would not be enough to contaminate people, but it was nonetheless a circular pattern of radiation. That freaked us out. I am telling you, right then I said, ‘Oh, shucks.’ He was serious about that, and I was there and saw where he had seen this pattern, and I [wondered] ‘Now, what could that be?’”[28]

--------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment