Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 385–393, 2008

Persistence of Past-Life Memories:

Study of Adults Who Claimed in Their Childhood to Remember a Past Life

ERLENDUR HARALDSSON

University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavik,

Abstract—Forty-two adults, aged 19 to 49, who claimed memories of a previous life when they were children were interviewed about their alleged memories. Over half of them had lost all these childhood memories but 38% unreservedly affirmed that they still had retained some of their past-life memories. These persons had been interviewed about their memories when they were children by Ian Stevenson or the author. The number of retained memories among those who still remembered something was about one-fifth of their original memories. The retained memories tended to center around persons they knew in their previous life and circumstances that led to their death. For half of the subjects the past-life memories had a positive impact on their life, but to some they had brought difficulties and unpleasant experiences, such as excessive attention given to them and teasing by other children. The great majority expressed general happiness with how their lives had developed. Their educational level was higher than that of their generation, as one-fourth had received some college or university education. A few of them still had phobias that they had had in their childhood and which they related to their previous life.

Introduction

Children who claim to have memories of a past life have been found in many countries, particularly in Asia, and several books and many reports have been written about them (Stevenson, 1987; Playfair, 2006; Tucker, 2005). Do they retain these alleged memories into adult life? Are certain kinds of memories likely to last longer than others? Until now no systematic attempts have been made to answer these questions. To attempt to uncover answers to these questions, the author conducted interviews with a representative sample of adults who, as children, spoke of previous-life memories.

It has been assumed that the alleged memories fade away in most instances by age five to seven. According to Stevenson (1987), ‘‘Children who remember verified previous lives (solved cases) continue speaking about them to an average age of just under seven and a half years, whereas children having unverified memories stop speaking about the previous lives at an average age of under six’’ (p. 106). Tucker (2005) writes, ‘‘Most of the children stop by the age of six or seven, and not only do they stop talking about the previous life, they often deny any memories of it when asked... Children vary, and some subjects report that they still have past-life memories even into adulthood just as some individuals report having a fair number of early childhood memories when they are adults. Nonetheless, the vast number of subjects seem to have forgotten all about the past life after a few years’’ (pp. 90–91).

Another important question is how these memories have affected the lives of these individuals. Have they proved to be a hindrance or did they enrich the subjects’ lives? Did it make a difference if the person of the previous life had been identified or if the details of the memories were verified or not? A related question is how these children fared in life as they matured and became adults. Phobias are a common characteristic in children claiming past-life memories. Do the phobias tend to disappear as the child grows up? These are some of the questions this investigation attempts to answer.

Stevenson investigated over 100 cases in Sri Lanka between 1960 and 1980 and published several reports on them (Stevenson 1977). The author studied 64 cases in Sri Lanka in 1988 to 1998 and published detailed accounts on a number of them (Haraldsson 1991, 2000a,b; Haraldsson & Samararatne 1999; Mills, Haraldsson & Keil 1994).

Procedures

Subjects

Included were adults who were at least 19 years old. The author had detailed files on each person of 17 such Sri Lankan cases that he had investigated. Stevenson had a comparable collection of files on 48 persons. The cases of this study were thus drawn from a pool of 65 cases.

Some subjects could not be traced, a few lived in faraway places and were dropped for practical reasons, two had died, and one was incapacitated in a mental institution. Interviews were conducted with 42 subjects whose homes were spread over a large part of Sri Lanka, 17 males and 25 females. Thirty cases were from Stevenson’s pool and originally interviewed by him in the late 1960s and 1970s. Twelve subjects were originally interviewed by Haraldsson between 1988 and 1990. The mean age of the subjects was 31.5 years (SD 1⁄4 8.7). For Stevenson’s cases the mean was 35.5 years (SD 1⁄4 7.1, range 21–49), and the mean was 21.5 years (SD 1⁄4 1.8, range 19–24) for Haraldsson’s cases.

Relatives

For verification purposes it was planned to interview one close relative of each subject. This was done in 36 instances (32 mothers, 3 fathers, and 1 older brother). In six instances no close relative was available for interviewing or close relatives lived too far away to be reached.Questionnaires

A 49-item questionnaire was developed for the subjects and a 35-item questionnaire for the relatives, with emphasis on questions regarding the alleged memories of the previous life. In addition, questions were asked about normal memories from early childhood, phobias in early life, visits to a family associated with the previous life, if a previous family had been identified, whether or not gifts were exchanged between the two families, and how widely known the case had become. There were also questions asked about the subjects’ thoughts regarding the positive and negative value of having past-life memories, and the impact it had on their lives. There were questions about health and happiness, occupation, marital status, and if the subjects had met anyone who, like themselves, had claimed to remember a previous life. Further questions will become evident in the results section.

Results

How Common Is It to Retain Previous-Life Memories into Adult Life?

Twelve percent of the subjects are sure that they still have clear memories of their past life, and further, 33% believe that they still have some of their childhood memories. These percentages combined reveal that 45% had some or clear memories, whereas 55% stated that all their memories have faded away. Further probing revealed that of those who still have some memories, one person was not sure about the source of her memories, another only remembered speaking of previous-life memories as a child but does not have these memories now, and one thought she might only have her memories because they were talked about so much in her family. This leaves us with 16 out of 42 persons (38%) who unreservedly affirm that they still retain at least some of their past- life memories, whereas three (7%) expressed doubt about the source of the memories that they still possessed (see Table 1).

Of 16 persons who reported still having past-life memories as a continuation of their childhood memories, five stated that they most clearly remembered persons that they knew in the previous life, four remembered clearly events or circumstances that led to their death, or how they died, and three most clearly remembered what they used to do or sometimes did.

When they were asked what they recalled second most clearly, four stated it was the mode of their death. Three subjects stated that it was the people that they had known, three stated what they used to do in their previous life, and two remembered where they had lived. See Table 2.

Comparison of Childhood and Adulthood Memories

How much did those 16 remember who still retained some of their memories about a previous life and felt sure that they were a continuation of their childhood memories? The average was 6.56 statements. Because of one particularly high value (24 remembered statements), the median is more descriptive and is 5.5 statements. This is on the average about one-fifth of the number of statements they claimed to remember in their childhood. Detailed results are given in Table 3. Unfortunately, the author failed to find any studies for comparison that examine how childhood memories are carried over to adulthood. Besides, such memories would certainly depend a lot on what kind of memories would be examined.

The average of six statements is far below the mean of 29 statements reported by the same children during their childhood period of remembering their past life. It was most common to remember three statements. Further details are found in Table 3.

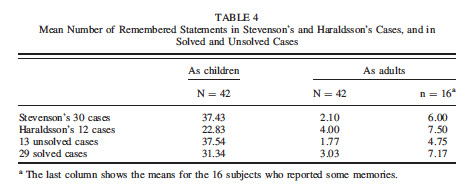

Stevenson investigated his 30 cases in the 1960s or 1970s, and they had a mean number of 37.43 remembered statements. Haraldsson studied his 12 cases at the end of the 1980s with a mean number of 22.83 statements. The mean number of statements presently remembered by Stevenson’s subjects was 2.10, compared to 4.00 by Haraldsson’s. These means are 6.00 and 7.50 statements if only those 16 subjects are included who retained some of their past-life memories. This may indicate that some forgetting also takes place after maturity is reached. Haraldsson’s subjects were on the average 14 years younger than Stevenson’s.

Actually, Stevenson had 48 cases from the 1960s or 1970s in our original datapool, and they had a mean number of 29 remembered statements. Haraldsson had 17 cases in the original datapool from the end of the 1980s, with a mean number of 28.60 statements. For some reason those subjects of Stevenson that were traced and interviewed remembered more statements as children than those that we did not interview (see Table 4).

Subjects of solved cases tended to recall slightly more statements as children (37.54 compared to 31.34 of unsolved cases) and this group remembers more statements as adults (3.03 compared to 1.77 when all subjects are included, and 7.17 versus 4.75 for those 16 who retained some past-life memories) but this difference between solved and unsolved cases is not significant.

What Impact Did the Memories Have?

Half of the subjects (51%) stated that their memories had been helpful and had a positive impact on them. A few mentioned that their memories confirmed their belief in reincarnation. One man stated that it had been pleasant to have these memories, but he had not benefitted from them in any way. One woman said that her childhood friends had shared their sweets with her when she told them about her memories. The closest relatives interviewed shared the view of the subjects, as 64% of them considered that the memories had been beneficial to the subjects.

Nine percent of the subjects reported that the memories had led to many unpleasant experiences, and to an additional 20% they brought some difficulties. Their difficulties tended to stem from excessive attention being given to them – too many people coming and wanting to hear about the previous life, and being asked questions they could not answer. Evidently quite a few did not like all the attention and questioning that followed. The close relatives expressed the view that the memories had brought some difficulties to 16% of the subjects when they were children.

About 30% of the subjects had received a great deal of attention, and 85% of the cases led to one or more articles in Sri Lankan newspapers. There was a significant agreement between the subjects and the closest family members about publication of newspaper articles on the case and the attention received by the case.

Some subjects had been teased by other children, some nicknamed or considered odd. Some reported mixed experiences, positive as well as negative. To over a third (37%) the memories had made no difference in their life one way or another.

Did they prefer this or the previous life? Over half clearly preferred the present life (55%), about a third had no preference or did not know which life they preferred, and 13% stated that they preferred the previous life that they remembered.

How Did Persons with Previous-Life Memories in Childhood Fare in Later Life?

The great majority of the subjects expressed general happiness with how their life was going in general, whereas 7% were unhappy about their present situation. How this relatively high degree of general happiness compares with their peers in Sri Lanka is hard to assess, but it may well be over the average. There is a high consistency between the subjects and the estimate of their closest relatives regarding the subjects’ general happiness with their life. Generally their health had been good, and only four had been hospitalized two times or more.

The educational level obtained by our subjects seemed somewhat higher than that of Sri Lankans of their generation, as one fourth had enjoyed some college or university education, about half had only completed the compulsory education, and one fourth had received some training or schooling beyond that.

The subjects seemed to be living normal productive lives as far as we could ascertain. One was working as a mathematician in a bank, another as an engineer, and one with computers. There were six housewives, five students, three teachers, and the rest were found in various occupations. Only two were unemployed, which is unusual for Sri Lanka, one was disabled through an accident, and one had become a drug-addict (Sri Lanka has a rather serious drug problem). 87% stated that they were reasonably satisfied with their occupation. Twenty-one people were single, 19 married, and most of them had children. One person was divorced. On the whole the data indicate that our subjects have fared reasonably well in life, probably somewhat above the average for their age group in Sri Lanka.

Childhood Fears and Phobias

Phobias are a common characteristic of children who claim past-life memories. Do the phobias follow them into adult life or disappear in late childhood? Of the 19 subjects who reported having particular fears when they were children, 12 considered the fears to be related to their previous life. Seven of them still had these fears, whereas in four of the subjects, the fears had disappeared when they were 6 to 10 years of age.

Contacts with the Previous Family

One of the areas explored was visits between the subjects and the families that had been identified as the previous family of the child. There were 29 such solved cases, including two in which the child was believed to be a family member or a relative reborn. In 19 of the 27 unrelated solved cases there had been visits between the families, in four instances only one or two, but usually much more frequent and taking place over a period of many years. In 11 cases the families had kept in contact up to the present time. Gifts were frequently exchanged between these families.

Discussion

Ever since Ian Stevenson started his investigations of children who claim to remember episodes from a past life, there has been some uncertainty about what portion of these children retain their memories into adult life, and what they then remember. Studies of individual cases have revealed that in a very large number of the children these memories have faded away around the time they go to school, and many of them also stop talking about them around this time.

Interviews with 42 adults with past-life memories as children reveal that over one-third of them have retained some of their early childhood memories or images that they experienced as from a previous life and which often – at least in part – consist of tragic and life-threatening events. This portion is higher than had been expected.

Childhood phobias related to the previous-life memories seem to be more resistant and even less likely to fade away than the memories. Furthermore, some of the children remember talking about their past life as children and what they said, but the memories themselves have faded away. In addition, there were some children who stated they were still aware of some past-life memories because their families had been talking about them. We did not include these cases as real past-life recollections. It is difficult to determine to what extent much talk within the family about the memories may contribute to keeping them alive, although we also have clear evidence from the study of child cases that the children often appear to have forgotten everything soon after they start to attend school.

One of the purposes of this project was to explore if the persistence of past-life memories was in any way related to the persistence of other pre-school memories that were not related to previous lives. No such trend was observed.

Subjects who retained some memories remembered about one-fifth of the original past-life memories from early childhood. How this compares to loss of childhood memories in general is hard to assess, as the author failed to find any studies that examine how childhood memories are carried over to adulthood.

On the basis of his interviews the author is inclined to think that previous-life memories may be relatively better retained than other memories from the same age. This impression needs formal testing, which may be difficult to do as events of early childhood are rarely recorded to the same extent that previous-life memories are in investigated cases of the reincarnation-type.

Two psychological studies in Sri Lanka have compared short term memories of children with and without past-life memories. In the first study children with past-life memories remembered significantly more of the content of a short story that was read to them than their peers did (Haraldsson, 1997). There was a trend in the same direction in the second study (Haraldsson et al., 2000). Whether this difference is only a sign of early maturity of these children or a general indication of a better memory throughout life remains an open question. For most of the persons of this study we have no memory test scores to explore if persons who retained some past-life memories scored higher in the memories tests than those who had lost all such memories.

Generally speaking, these children seem to have fared well in life, and a larger number of them than their peers managed to reach a high level of education in the highly competitive educational system of Sri Lanka. This finding is in line with the results of two psychological studies conducted in Sri Lanka which showed that these children tend to be more gifted and harder working as pupils or students than their peers (Haraldsson, 1997; Haraldsson, Fowler & Periyannanpillai, 2000).

A few of these persons were also negatively affected by their past-life memories – apart from the phobias – as some of them had as children suffered from much attention that they received, and were sometimes teased by other children. However, the great majority of these adults expressed general happiness with their present situation in life and seemed to lead productive and healthy lives in society.

References

Haraldsson, E. (1991). Children claiming past-life memories: Four cases in Sri Lanka. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 5, 233–262.

Haraldsson, E. (1997). Psychological comparison between ordinary children and those who claim previous-life memories. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 11, 323–335.

Haraldsson, E. (2000a). Birthmarks and claims of previous life memories I. The case of Purnima Ekanayake. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 64(858), 16–25.

Haraldsson, E. (2000b). Birthmarks and claims of previous life memories II. The case of Chatura Karunaratne. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 64, 82–92.

Haraldsson, E., Fowler, P., & Periyannanpillai, P. (2000). Psychological characteristics of children who speak of a previous life: A further field study in Sri Lanka. Transcultural Psychiatry, 37, 525–544.

Haraldsson, E., & Samararatne, G. (1999). Children who speak of memories of a previous life as a Buddhist monk: Three new cases. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 63, 268–291. Mills, A., Haraldsson, E., & Jurgen Keil, H. H. (1994). Replication studies of cases suggestive of reincarnation by three independent investigators. Journal of the American Society for Psychical

Research. 88, 207–219.

Playfair, G. L. (2006). New Clothes for Old Souls. Worldwide Evidence for Reincarnation. Druze

Heritage Foundation.

Stevenson, I. (1977). Cases of the reincarnation type. Vol. 2. Ten cases in Sri Lanka. University of

Virginia Press.

Stevenson, I. (1987). Children Who Remember Past Lives. A Question of Reincarnation. University of

Virginia Press.

Tucker, J. B. (2005). Life before Life. A Scientific Investigation of Children’s Memories of a Previous

Life. St. Martins Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment