http://frontiers-of-anthropology.blogspot.gr/search/label/Channel%20Islands

Science News

Funded primarily by grants from the National Science Foundation, the team also found thousands of artifacts made from chert, a flint-like rock used to make projectile points and other stone tools.

Some of the intact projectiles are so delicate that their only practical use would have been for hunting on the water, said Jon Erlandson, professor of anthropology and director of the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon. He has been conducting research on the islands for more than 30 years.

"This is among the earliest evidence of seafaring and maritime adaptations in the Americas, and another extension of the diversity of Paleoindian economies," Erlandson said. "The points we are finding are extraordinary, the workmanship amazing. They are ultra thin, serrated and have incredible barbs on them. It's a very sophisticated chipped-stone technology." He also noted that the stemmed points are much different than the iconic fluted points left throughout North America by Clovis and Folsom peoples who hunted big game on land.

The artifacts were recovered from three sites that date to the end of the Pleistocene epoch on Santa Rosa and San Miguel islands, which in those days were connected as one island off the California coast. Sea levels then were 50 to 60 meters (about 160-200 feet) below modern levels. Rising seas have since flooded the shorelines and coastal lowlands where early populations would have spent most of their time.

Erlandson and his colleagues have focused their search on upland features such as springs, caves, and chert outcrops that would have drawn early maritime peoples into the interior. Rising seas also may have submerged evidence of even older human habitation of the islands.

The newly released study focuses on the artifacts and animal remains recovered, but the implications for understanding the peopling of the Americas may run deeper.

The technologies involved suggest that these early islanders were not members of the land-based Clovis culture, Erlandson said. No fluted points have been found on the islands. Instead, the points and crescents are similar to artifacts found in the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau areas, including pre-Clovis levels at Paisley Caves in eastern Oregon that are being studied by another UO archaeologist, Dennis Jenkins.

Last year, Charlotte Beck and Tom Jones, archaeologists at New York's Hamilton College who study sites in the Great Basin, argued that stemmed and Clovis point technologies were separate, with the stemmed points originating from Pacific Coast populations and not, as conventional wisdom holds, from the Clovis people who moved westward from the Great Plains. Erlandson and colleagues noted that the Channel Island points are also broadly similar to stemmed points found early sites around the Pacific Rim, from Japan to South America.

Six years ago, Erlandson proposed that Late Pleistocene sea-going people may have followed a "kelp highway" stretching from Japan to Kamchatka, along the south coast of Beringia and Alaska, then southward down the Northwest Coast to California. Kelp forests are rich in seals, sea otters, fish, seabirds, and shellfish such as abalones and sea urchins.

"The technology and seafaring implications of what we've found on the Channel Islands are magnificent," said study co-author Torben C. Rick, curator of North American Archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution. "Some of the paleo-ecological and subsistence implications are also very important. These sites indicate very early and distinct coastal and island subsistence strategies, including harvest of red abalones and other shellfish and fish dependent on kelp forests, but also the exploitation of larger pinnipeds and waterfowl, including an extinct flightless duck.

"This combination of unique hunting technologies found with marine mammal and migratory waterfowl bones provides a very different picture of the Channel Islands than what we know today, and indicates very early and diverse maritime life ways and foraging practices," Rick said. "What is so interesting is that not only do the data we have document some of the earliest marine mammal and bird exploitation in North America, but they show that very early on New World coastal peoples were hunting such animals and birds with sophisticated technologies that appear to have been refined for life in coastal and aquatic habitats."

The stemmed points found on the Channel Islands range from tiny to large, probably indicating that they were used for hunting a variety of animals.

"We think the crescents were used as transverse projectile points, probably for hunting birds. Their broad stone tips, when attached to a dart shaft provided a stone age shotgun-approach to hunting birds in flight," Erlandson said. "These are very distinctive artifacts, hundreds of which have been found on the Channel Islands over the years, but rarely in a stratified context, he added. Often considered to be between 8,000 and 10,000 years old in California, "we now have crescents between 11,000 and 12,000 years old, some of them associated with thousands of bird bones."

The next challenge, Erlandson and Rick noted, is to find even older archaeological sites on the Channel Islands, which might prove that a coastal migration contributed to the initial peopling of the Americas, now thought to have occurred two to three millennia earlier.

The 13 co-authors on the study with Erlandson and Rick were: Todd J. Braje, professor of anthropology at Humboldt State University in Arcata, Calif.; UO anthropology professors Douglas J. Kennett and Madonna L. Moss; Brian Fulfrost of the geography department of San Francisco State University; Daniel A. Guthrie of the Joint Science Department, Claremont McKenna, Scripps and Pitzer Colleges of Claremont, Calif.; Leslie Reeder, anthropology department of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; Craig Skinner of the Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory in Corvallis, Ore.; Jack Watts of Kellogg College at Oxford University, United Kingdom; and UO graduate students Molly Casperson, Nicholas Jew, Brendan Culleton, Tracy Garcia and Lauren Willis.

Do archaeological sites in the Channel Islands reveal a coastal migration into the Americas?

Millennia before American pioneers charged westward in search of land and fortune, humans pursued a different version of manifest destiny. Driven by changes in the environment or growing populations, and perhaps a basic human urge to explore, they weathered the frigid Siberian Arctic, wending through what is now the Bering Strait into North America. By at least 14,000 years ago, early settlers had spread through the continent and parts of South America.

Millennia before American pioneers charged westward in search of land and fortune, humans pursued a different version of manifest destiny. Driven by changes in the environment or growing populations, and perhaps a basic human urge to explore, they weathered the frigid Siberian Arctic, wending through what is now the Bering Strait into North America. By at least 14,000 years ago, early settlers had spread through the continent and parts of South America.

Just how humans first entered the New World is still actively debated. For decades, the dominant theory described a migration from Siberia through a land-locked, ice-free corridor into Canada. These days, consensus is growing for an alternative “coastal migration theory,” where people followed the Pacific Coast from Asia to the Americas when the inland route was still covered by glaciers. The idea gained traction in 1997, after a pivotal find in Monte Verde, Chile, revealed signs of human occupation dating back 14,000 years. Recent discoveries within California’s Channel Islands National Park have bolstered the coastal migration theory, revealing that seafaring peoples settled the islands at least 13,000 years ago, hunting seals, fishing, and collecting shellfish and seaweeds.

Located roughly 20 miles off the coast of Santa Barbara, the Channel Islands are an archaeologist’s dream. Unlike the mainland, these sites aren’t threatened by destructive development or burrowing animals notorious for digging up the past. Instead, the park’s remaining archaeological sites are fairly pristine, like “a prehistoric layer cake” packed with information, according to Torben Rick, curator of North American Archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1999, news broke that human remains recovered from Santa Rosa Island four decades earlier had been radio-carbon-dated to about 13,000 years ago, some of the oldest human bones in North America. Their presence on Santa Rosa supported a coastal migration, according to John Johnson, the archaeologist who dated them. Yet with the absence of tools and other tell-tale artifacts, it wasn’t clear who these people were.

Jon Erlandson, director of the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History, has studied the earliest sites in the area for decades. Erlandson and Rick recently shined light on early Channel Islands life through discoveries of their own. On Santa Rosa Island, the duo hit a jackpot—by accident. “We were literally on a walk in the park,” says Erlandson, when an eroded area caught his eye, and he walked over to get a closer look. “It was full of bird bones and stone tools,” he says, “so we knew this site need some serious work.” They were right. Further investigation revealed a treasure trove of deeply buried artifacts and animal bones eroding from the sea cliff—items that dated about 11,800 years old.

With logistical support from Channel Islands National Park and funding from the National Science Foundation, they worked with graduate students and other colleagues to excavate thousands of bone fragments from fish, geese, seabirds, and marine mammals. They also found dozens of small barbed points, probably used to spear sea life, crescents to hunt birds, and other tools fashioned mostly from local island cherts, a flint-like rock. Well suited to marine environments, these are more similar to tools recovered in Northeast Asia and the Pacific Northwest than ones found in North America’s interior.

Excavations on neighboring San Miguel Island unearthed more clues to the past. In addition to tools, the team found shell mounds, which suggested that early settlers feasted on mussels, red abalone, crabs, and other shellfish. “The sites complement each other nicely,” says Erlandson. Collectively, their artifacts date back between about 11,400 and 12,200 years ago and paint a picture of people who were probably more than just passers-by. They likely used Santa Rosa’s hunting site during the winter, when migratory birds such as geese would have been abundant. Erlandson says it’s not clear when they collected shellfish on San Miguel, but it was probably primarily during the summer and fall.

“These are people who were familiar with their island environment and knew what they were doing,” says Rick. More permanent villages may have existed closer to the ancient coastline, which has since been swallowed by rising post-glacial seas (four of the five park islands were once melded as one, until rising ocean waters separated them). These pioneers were probably “living the good life by the sea,” says Erlandson. “These may have been glory days, when resources were truly abundant and the islands and adjacent mainland were relatively uncrowded.”

Erlandson and Rick’s recent finds aren’t old enough to confirm a coastal migration, but they do show that early humans occupied the Pacific Coast around the same time that other humans roamed North America’s interior. Perhaps the most definitive lesson that these park findings convey, however, is that “the peopling of the Americas is a lot more complex than we thought it was a decade ago,” says Erlandson. “The holy grail would be to find a 15,000-year-old site,” one that predates older human settlements such as at Monte Verde in Chile. With the park only 40 percent surveyed—and offshore waters still largely unexplored—there may be a lot left to discover.

http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=22931

Ancient Settlements off the coast of California.

Chumash village sites dot the islands. Although the Chumash met European explorers in the 1600's. their culture on the islands date back thousands of years.

"Arlington Woman," is an individual carbon dated to 13000 years ago by a small fragment of femur. At that time lower sea levels joined four of the five present channel islands together and the climate was much cooler. Human remains and artifacts dated to this period supports a coastal colonization path to the Americas from Asia. The islands were continuously occupied from a later time - roughly 10,000 years ago and onwards.

The location given is for San Miguel island, the farthest from the mainland. Here and in other locations shell middens can be seen. Erosion frequently uncovers artifacts like grinding bowls, tools, and midden bone remains. A brief history of the pre-contact island occupation can be found here at the National Park website.

The National Park Service maintains the islands. The mainland visitor's center is in Ventura, CA. The island's themselves are only accessible by park concessionaire boats or private boat. There are camping areas on each of the larger islands and day trips can be planned as well. Once on the islands you proceed by kayak or on foot.

Note: A long-term health decline—including a gradual shrinking—among prehistoric Indians in California. See comment.

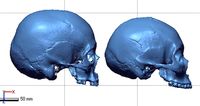

[At just a quick assessment, I'd say the blue skull on the left is Transatlantic Cromagnon from the Solutrean crossing while the blue skull on the right is plausibly via Transpacific crossing and looks to have Australoid and/or Prehistoric East Asian morphology. I am guessing the circumpacific Australoid movement came in first and then the more common Paleoindian element came in and superimposed themselves on it, which also seems to be the pattern in Chile. In Chile and other parts of South America, may I reiterate, the earliest circumpacific colonials are stated to have arrived as far back as 30000 years ago. Best Wishes, Dale D.]

Science News

California Islands Give Up Evidence of Early Seafaring: Numerous Artifacts Found at Late Pleistocene Sites On the Channel Islands

ScienceDaily (Mar. 3, 2011) — Evidence for a diversified sea-based economy among North American inhabitants dating from 12,200 to 11,400 years ago is emerging from three sites on California's Channel Islands.

Reporting in the March 4 issue of Science, a 15-member team led by University of Oregon and Smithsonian Institution scholars describes the discovery of scores of stemmed projectile points and crescents dating to that time period. The artifacts are associated with the remains of shellfish, seals, geese, cormorants and fish.Funded primarily by grants from the National Science Foundation, the team also found thousands of artifacts made from chert, a flint-like rock used to make projectile points and other stone tools.

Some of the intact projectiles are so delicate that their only practical use would have been for hunting on the water, said Jon Erlandson, professor of anthropology and director of the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon. He has been conducting research on the islands for more than 30 years.

"This is among the earliest evidence of seafaring and maritime adaptations in the Americas, and another extension of the diversity of Paleoindian economies," Erlandson said. "The points we are finding are extraordinary, the workmanship amazing. They are ultra thin, serrated and have incredible barbs on them. It's a very sophisticated chipped-stone technology." He also noted that the stemmed points are much different than the iconic fluted points left throughout North America by Clovis and Folsom peoples who hunted big game on land.

The artifacts were recovered from three sites that date to the end of the Pleistocene epoch on Santa Rosa and San Miguel islands, which in those days were connected as one island off the California coast. Sea levels then were 50 to 60 meters (about 160-200 feet) below modern levels. Rising seas have since flooded the shorelines and coastal lowlands where early populations would have spent most of their time.

Erlandson and his colleagues have focused their search on upland features such as springs, caves, and chert outcrops that would have drawn early maritime peoples into the interior. Rising seas also may have submerged evidence of even older human habitation of the islands.

The newly released study focuses on the artifacts and animal remains recovered, but the implications for understanding the peopling of the Americas may run deeper.

The technologies involved suggest that these early islanders were not members of the land-based Clovis culture, Erlandson said. No fluted points have been found on the islands. Instead, the points and crescents are similar to artifacts found in the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau areas, including pre-Clovis levels at Paisley Caves in eastern Oregon that are being studied by another UO archaeologist, Dennis Jenkins.

Last year, Charlotte Beck and Tom Jones, archaeologists at New York's Hamilton College who study sites in the Great Basin, argued that stemmed and Clovis point technologies were separate, with the stemmed points originating from Pacific Coast populations and not, as conventional wisdom holds, from the Clovis people who moved westward from the Great Plains. Erlandson and colleagues noted that the Channel Island points are also broadly similar to stemmed points found early sites around the Pacific Rim, from Japan to South America.

Six years ago, Erlandson proposed that Late Pleistocene sea-going people may have followed a "kelp highway" stretching from Japan to Kamchatka, along the south coast of Beringia and Alaska, then southward down the Northwest Coast to California. Kelp forests are rich in seals, sea otters, fish, seabirds, and shellfish such as abalones and sea urchins.

"The technology and seafaring implications of what we've found on the Channel Islands are magnificent," said study co-author Torben C. Rick, curator of North American Archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution. "Some of the paleo-ecological and subsistence implications are also very important. These sites indicate very early and distinct coastal and island subsistence strategies, including harvest of red abalones and other shellfish and fish dependent on kelp forests, but also the exploitation of larger pinnipeds and waterfowl, including an extinct flightless duck.

"This combination of unique hunting technologies found with marine mammal and migratory waterfowl bones provides a very different picture of the Channel Islands than what we know today, and indicates very early and diverse maritime life ways and foraging practices," Rick said. "What is so interesting is that not only do the data we have document some of the earliest marine mammal and bird exploitation in North America, but they show that very early on New World coastal peoples were hunting such animals and birds with sophisticated technologies that appear to have been refined for life in coastal and aquatic habitats."

The stemmed points found on the Channel Islands range from tiny to large, probably indicating that they were used for hunting a variety of animals.

"We think the crescents were used as transverse projectile points, probably for hunting birds. Their broad stone tips, when attached to a dart shaft provided a stone age shotgun-approach to hunting birds in flight," Erlandson said. "These are very distinctive artifacts, hundreds of which have been found on the Channel Islands over the years, but rarely in a stratified context, he added. Often considered to be between 8,000 and 10,000 years old in California, "we now have crescents between 11,000 and 12,000 years old, some of them associated with thousands of bird bones."

The next challenge, Erlandson and Rick noted, is to find even older archaeological sites on the Channel Islands, which might prove that a coastal migration contributed to the initial peopling of the Americas, now thought to have occurred two to three millennia earlier.

The 13 co-authors on the study with Erlandson and Rick were: Todd J. Braje, professor of anthropology at Humboldt State University in Arcata, Calif.; UO anthropology professors Douglas J. Kennett and Madonna L. Moss; Brian Fulfrost of the geography department of San Francisco State University; Daniel A. Guthrie of the Joint Science Department, Claremont McKenna, Scripps and Pitzer Colleges of Claremont, Calif.; Leslie Reeder, anthropology department of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas; Craig Skinner of the Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory in Corvallis, Ore.; Jack Watts of Kellogg College at Oxford University, United Kingdom; and UO graduate students Molly Casperson, Nicholas Jew, Brendan Culleton, Tracy Garcia and Lauren Willis.

Above Chumash settlement such as found on the Channel Islands and below a typical canoe. Recently (Ethnographioc Present) these were up to 30 feet long but there are hunts that hundred foot long canoes had been used in the past.

Maiden Voyage

Do archaeological sites in the Channel Islands reveal a coastal migration into the Americas?

By Julie Leibach

Millennia before American pioneers charged westward in search of land and fortune, humans pursued a different version of manifest destiny. Driven by changes in the environment or growing populations, and perhaps a basic human urge to explore, they weathered the frigid Siberian Arctic, wending through what is now the Bering Strait into North America. By at least 14,000 years ago, early settlers had spread through the continent and parts of South America.

Millennia before American pioneers charged westward in search of land and fortune, humans pursued a different version of manifest destiny. Driven by changes in the environment or growing populations, and perhaps a basic human urge to explore, they weathered the frigid Siberian Arctic, wending through what is now the Bering Strait into North America. By at least 14,000 years ago, early settlers had spread through the continent and parts of South America.Just how humans first entered the New World is still actively debated. For decades, the dominant theory described a migration from Siberia through a land-locked, ice-free corridor into Canada. These days, consensus is growing for an alternative “coastal migration theory,” where people followed the Pacific Coast from Asia to the Americas when the inland route was still covered by glaciers. The idea gained traction in 1997, after a pivotal find in Monte Verde, Chile, revealed signs of human occupation dating back 14,000 years. Recent discoveries within California’s Channel Islands National Park have bolstered the coastal migration theory, revealing that seafaring peoples settled the islands at least 13,000 years ago, hunting seals, fishing, and collecting shellfish and seaweeds.

Located roughly 20 miles off the coast of Santa Barbara, the Channel Islands are an archaeologist’s dream. Unlike the mainland, these sites aren’t threatened by destructive development or burrowing animals notorious for digging up the past. Instead, the park’s remaining archaeological sites are fairly pristine, like “a prehistoric layer cake” packed with information, according to Torben Rick, curator of North American Archaeology at the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1999, news broke that human remains recovered from Santa Rosa Island four decades earlier had been radio-carbon-dated to about 13,000 years ago, some of the oldest human bones in North America. Their presence on Santa Rosa supported a coastal migration, according to John Johnson, the archaeologist who dated them. Yet with the absence of tools and other tell-tale artifacts, it wasn’t clear who these people were.

Jon Erlandson, director of the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History, has studied the earliest sites in the area for decades. Erlandson and Rick recently shined light on early Channel Islands life through discoveries of their own. On Santa Rosa Island, the duo hit a jackpot—by accident. “We were literally on a walk in the park,” says Erlandson, when an eroded area caught his eye, and he walked over to get a closer look. “It was full of bird bones and stone tools,” he says, “so we knew this site need some serious work.” They were right. Further investigation revealed a treasure trove of deeply buried artifacts and animal bones eroding from the sea cliff—items that dated about 11,800 years old.

With logistical support from Channel Islands National Park and funding from the National Science Foundation, they worked with graduate students and other colleagues to excavate thousands of bone fragments from fish, geese, seabirds, and marine mammals. They also found dozens of small barbed points, probably used to spear sea life, crescents to hunt birds, and other tools fashioned mostly from local island cherts, a flint-like rock. Well suited to marine environments, these are more similar to tools recovered in Northeast Asia and the Pacific Northwest than ones found in North America’s interior.

Excavations on neighboring San Miguel Island unearthed more clues to the past. In addition to tools, the team found shell mounds, which suggested that early settlers feasted on mussels, red abalone, crabs, and other shellfish. “The sites complement each other nicely,” says Erlandson. Collectively, their artifacts date back between about 11,400 and 12,200 years ago and paint a picture of people who were probably more than just passers-by. They likely used Santa Rosa’s hunting site during the winter, when migratory birds such as geese would have been abundant. Erlandson says it’s not clear when they collected shellfish on San Miguel, but it was probably primarily during the summer and fall.

“These are people who were familiar with their island environment and knew what they were doing,” says Rick. More permanent villages may have existed closer to the ancient coastline, which has since been swallowed by rising post-glacial seas (four of the five park islands were once melded as one, until rising ocean waters separated them). These pioneers were probably “living the good life by the sea,” says Erlandson. “These may have been glory days, when resources were truly abundant and the islands and adjacent mainland were relatively uncrowded.”

Erlandson and Rick’s recent finds aren’t old enough to confirm a coastal migration, but they do show that early humans occupied the Pacific Coast around the same time that other humans roamed North America’s interior. Perhaps the most definitive lesson that these park findings convey, however, is that “the peopling of the Americas is a lot more complex than we thought it was a decade ago,” says Erlandson. “The holy grail would be to find a 15,000-year-old site,” one that predates older human settlements such as at Monte Verde in Chile. With the park only 40 percent surveyed—and offshore waters still largely unexplored—there may be a lot left to discover.

http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=22931

California Channel Islands - Ancient Village or Settlement in United States in The West |

|

Chumash village sites dot the islands. Although the Chumash met European explorers in the 1600's. their culture on the islands date back thousands of years.

"Arlington Woman," is an individual carbon dated to 13000 years ago by a small fragment of femur. At that time lower sea levels joined four of the five present channel islands together and the climate was much cooler. Human remains and artifacts dated to this period supports a coastal colonization path to the Americas from Asia. The islands were continuously occupied from a later time - roughly 10,000 years ago and onwards.

The location given is for San Miguel island, the farthest from the mainland. Here and in other locations shell middens can be seen. Erosion frequently uncovers artifacts like grinding bowls, tools, and midden bone remains. A brief history of the pre-contact island occupation can be found here at the National Park website.

The National Park Service maintains the islands. The mainland visitor's center is in Ventura, CA. The island's themselves are only accessible by park concessionaire boats or private boat. There are camping areas on each of the larger islands and day trips can be planned as well. Once on the islands you proceed by kayak or on foot.

Note: A long-term health decline—including a gradual shrinking—among prehistoric Indians in California. See comment.

[At just a quick assessment, I'd say the blue skull on the left is Transatlantic Cromagnon from the Solutrean crossing while the blue skull on the right is plausibly via Transpacific crossing and looks to have Australoid and/or Prehistoric East Asian morphology. I am guessing the circumpacific Australoid movement came in first and then the more common Paleoindian element came in and superimposed themselves on it, which also seems to be the pattern in Chile. In Chile and other parts of South America, may I reiterate, the earliest circumpacific colonials are stated to have arrived as far back as 30000 years ago. Best Wishes, Dale D.]

No comments:

Post a Comment