Goblet d'Alviella-SWASTIKA

The Migration of Symbols

by Goblet d'Alviella

[1894]

========================================

CHAPTER II.

ON THE GAMMADION OR SWASTIKA.

- I. Geographical distribution of the gammadion.—Different patterns of the gammadion.—Its common occurrence amongst all the nations of the Old World, with the exception of the Egyptians, the Phœnicians, the Mesopotamians, and the Persians.—The fylfot.—The swastika.

- II. Previous interpretations of the gammadion.—Opinions of Messrs. George Birdwood, Alexander Cunningham, Waring, W. Schwartz, Emile Burnouf, R. P. Greg, Ludwig Müller, and others.

- III. Probable meaning of the gammadion.—The gammadion a charm.—The gammadion symbolical of the solar movement, and, by analogy, of the heavenly bodies in general.—The arms of the gammadion are rays which move.—Connection between the tétrascèle and the triscèle.—Figures connected with the gammadion.—Equivalence of thegammadion and certain solar images.—The Three Steps of Vishnu.—Lunar tétrascèles.

- IV. Cradle of the gammadion.—Was it conceived simultaneously in several places?—Uniformity of its meaning and use.—Discussion as to its Aryan or Pelasgic origin.—Information furnished by the "whorls" of Hissarlik and the prehistoric pottery of Northern Italy.—The question is archæological, not ethnical.—Conclusions.

I. Geographical Distribution of the Gammadion.

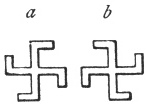

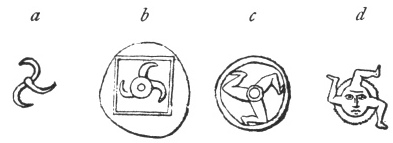

Fig. 14. Gammadions

The name gammadion is given to that form of cross whose extremities are bent back at right

angles, as if to form four gammas joined together at the base (fig. 14).

It may be called a cross pattée when the bent parts end in a point so as to form a sort of foot (fig. 15a), and a cross with hooks when the arms after being bent a first time are again twisted either inwards (15b), or outwards. Lastly, it takes the name of tétrascèle when the arms are rounded off whilst curving backwards.

Fig. 15. Varieties of the Gammadion

With the exception of the solar Disk and the Greek Cross there are few symbolical marks so widely distributed.

Dr. Schliemann, exploring the débris of the towns piled upon the plateau of Hissarlik, beginning with the second or "burnt city," which the learned explorer identifies with the Ilium of Priam, 1 found innumerable gammadions, especially amongst the decorations of those terra cotta disks which have been thought to be "whorls," and which served perhaps as ex voto. 2 It likewise ornaments certain idols of feminine shape, which recall roughly the appearance of the Chaldæan Ishtar; in one of these statuettes, a leaden one, it occupies the centre of the triangle denoting the belly. 3

In Greece, as in Cyprus and at Rhodes, it first appears on that pottery with geometrical ornamentation which constitutes the second period of Grecian ceramics; 1 it then passes to those vases with decorations taken from living objects, whose appearance seems to coincide with the development of Phœnician influences on the shores of Greece. 2

It is seen on the archaic pottery of Cyprus, and of Rhodes, and of Athens, on both sides of the conventional Tree, so frequently reproduced on the inscribed monuments of Hither Asia between two monsters facing each other. It appears on an Athenian vase in a burial scene, three times repeated in front of the funeral car. On a vase from Thera several gammadions are reproduced round an image of the Persian Artemis. At Mycenæ it figures on ornaments collected during Dr. Schliemann's excavations. 5 At Pergamus it adorns the balustrade of the portico which surrounded the temple of Athene, and at Orchomenus the sculptured roof of the so-called nuptial chamber in the palace of the Treasury. 6 Lastly, when the introduction of money disclosed a new outlet for the symbolic forms of religion and of art, it became a favourite emblem in the coinage, not only of the Archipelago and of Greece Proper, but also of Macedon, Thrace, Crete, Lycia, and Paphlagonia.

From Corinth, where it figures amongst the most ancient mint marks, it passed to Syracuse under Timoleon, to be afterwards spread abroad on the coins of Sicily and of Magna Græcia. 1 In Northern Italy it was known even before the advent of the Etruscans, for it has been met with on pottery dating from the terramare civilization. 2 It appears also on the roof of those ossuaries, in the form of a hut, which reproduce on a small scale the wicker hovels of the people of that epoch. 3 In the Villanova period it adorns vases with geometrical decorations found at Cære, Chiusi, Albano, and at Cumæ, 4 and when Etruria became accessible to oriental influences it appears on fibulæ and other golden ornaments.

At a still later period it is found on the breasts of personages decorating the walls of a Samnite tomb near Capua; 6 lastly it appears as a motif for decoration in the Roman mosaics. It is singular that at Rome itself it has not been met with on any monument prior to the third, or perhaps the fourth, century of our era. About that period the Christians of the Catacombs had no hesitation in including it amongst their representations of the Cross of Christ. Not only did they carve it upon the tombs, but they also used it to ornament the garments of certain priestly personages, such as the fossores, and even the tunic of the Good Shepherd. 7 At Milan it forms a row of curved Crosses round the pulpit of St. Ambrose.

On the other hand, it appears to have been widely distributed throughout the provinces of the Roman empire, especially among the Celts, where in many cases it is difficult to decide whether it is connected with imported civilization, or with indigenous tradition. From Switzerland, and even from the Danubian countries, to the most remote parts of Great Britain, it has been found on vases, on metal plates, on fibulæ, on sword belts, and on arms. 1 In England it adorns fragments of mosaics collected from the ruins of several villas, 2 as well as a funeral urn unearthed in a mound of the bronze age. 3 In Gaul it is observed frequently enough on coins ranging from the third century B.C. to the third century of our era, and even later, for it is met with on a Merovingian piece. 4 We may add that it already figures on fragments of pottery and even on terra cotta matrices found in a lacustrine city in Lake Bourget. 5

In Belgium, we meet with it at Estinnes (Hainault) and at Anthée (Province of Namur) in tile débris dating back to the Roman epoch. 6 It is also seen repeated several times, in association with the Lotus-flower, among the inscriptions on tombstones discovered, some years ago, in the Belgo-Roman cemetery of Juslenville, near Pepinster (fig. 16).

An interesting discussion, arose in the Institut archéologique liégeois as to whether—in spite of the invocation D[iis] M[anibus]—the presence of thegammadion did not imply the Christian character of this sepulchral monument. 1 To the arguments brought forward to refute this theory we may add that a sepulchral stele of an unquestionably

Fig. 16. Tombstone from Juslenville

(Institut archéologique liègeois, vol. x. (1870), pl. xiii.)

(Institut archéologique liègeois, vol. x. (1870), pl. xiii.)

pagan character, discovered in Algeria, offers an analogous combination of two gammadions placed over a Wheel.

Fig. 17. Libyan Sepulchral Stele.

(Proceedings of the Soc. franc. de numism. et d’archéol., vol. ii., pl. iii. 3.)

(Proceedings of the Soc. franc. de numism. et d’archéol., vol. ii., pl. iii. 3.)

The fact may be mentioned that in the middle of the Christian era, eleven or twelve centuries later, the gammadion reappears on a sepulchre in the same Belgian province. On a tombstone of the fourteenth century, discovered in 1871, during the construction of a tunnel at Huy, three personages are sculptured, one of whom is a priest clothed in a chasuble, and on this chasuble three bands of gammadions can be distinctly seen. 1

The gammadion, associated with the Wheel, as well as with the Thunderbolt, likewise adorns votive altars found, in England, and near the Pyrenees, on the site of Roman encampments. 2

Fig. 18. Altar in the Toulouse Museum.

(Reveu archéologique de 1880, vol. xl. p. 17.)

(Reveu archéologique de 1880, vol. xl. p. 17.)

At Velaux, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, there has been found the headless statue of a god sitting cross-legged, who bore on its breast a row of crocketed crosses surmounting another row of equilateral crosses. 3

In Ireland, however, and in Scotland, the gammadion seems really to have marked Christian sepulchres, for it is met with on tombstones associated with Latin Crosses. 4

The Rev. Charles Graves, Bishop of Limerick, has described an ogham stone found in an abandoned

cemetery in Kerry, which he believes to belong to the sixth century; it bears an arrow between two gammadions. 1

The Anglo-Saxons gave to the gammadion the name of fylfot, from the Norse fiöl (full, viel = "numerous"), and fot (foot). 2 It has been observed on pottery and funeral urns of the bronze age in Silesia, in Pomerania, and the eastern islands of Denmark. In the following ages it is met with on ornaments, on sword-hilts, on golden brackets, on sculptured rocks, and on tombstones. 3 Amongst the Scandinavians it ended by combining, doubtlessly

Fig. 19. Cross On A Runic Stone From Sweden.

(Ludwig Müller, p. 94, fig. a.)

(Ludwig Müller, p. 94, fig. a.)

under the influence of Christianity, with the Latin Cross.

In an old Danish church it ornaments baptismal fonts which date from the early times of Christianity. 4 In Iceland, according to Mr. Hjaltalin, it is still in use at the present day as a magic sign. 5

Amongst the Slays and Finns it has not yet been found, save in a sporadic state, and about the period of their conversion to Christianity only. We may remark, by the way, that it is very difficult

to determine the age and nationality of the terra cotta or bronze objects on which it has been observed in countries of mixed or superposed races, such as Hungary, Poland, Lithuania and Bohemia.

In the Caucasus, M. Chantre has met with it on ear-drops, ornamental plates, sword-hilts, and other objects found in burial-places dating back to the bronze period and the first iron age. 1

Amongst the Persians its presence has been pointed out on some Arsacian and Sassanian coins only. 2

The Hittites introduced it on a bas-relief at Ibriz, in Lycaonia, where it forms a border on the dress of a king, or priest, who offers up a sacrifice to a god. 3

The Phœnicians do not seem to have known or, at least, to have used it, except on some of the coins which they struck in Sicily in imitation of Greek pieces. A coin of Byzacium on which it is figured, near the head of Astarte, dates from the reign of Augustus. 4 It is not met with either in Egypt, in Assyria, or in Chaldæa.

In India it bears the name of swastika, when its arms are bent towards the right (fig. 14a), and sauwastika when they are turned in the other direction (fig. 14b). The word swastika is a derivative of swasti, which again comes from su = well, and the verb asti = it is; the expression would seem therefore to correspond with a Greek formula—εὐ εστὶ, and, in fact, amongst the Hindus as amongst the Buddhists, its representation has always passed for a propitious sign. 1

The grammarian Panini mentions it as a character used for earmarking cattle. We see in the Ramayana that the ships of the fleet, on which Bharata embarked for Ceylon, bore, doubtlessly on their bows, the sign of the swastika. 2 Passing now to inscribed monuments we find the gammadion on the bars of silver, shaped like dominos, which, in certain parts of India, preceded the use of money proper. 3

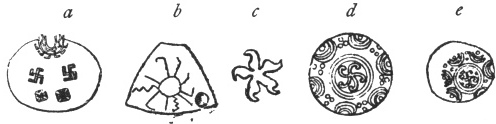

It even appears upon a coin of Krananda, which is held to be the oldest Indian coin, and which is

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

likewise remarkable as exhibiting the first representation of the trisula. 4

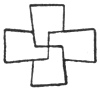

Occurring frequently at the beginning and the end of the most ancient Buddhist inscriptions, several examples of it are to be seen on the Foot-Prints of Buddha sculptured at Amravati. 5 The swastika represents, moreover, according to Buddhist tradition, the first of the sixty-five marks which distinguished the Master's feet, whilst the fourth is formed by the sauwastika, and the third by the nandyavarta, a kind of labyrinth, which, in the manner of the Greek meander, may be connected with the gammadion. 1

Fig. 21. The Nandyavarta.

It must be observed that amongst the Jains, the gammadion is regarded as the emblem of Suparsva, the seventh of the twenty-four Tirthankaras, whilst the nandyavarta is that of the eighteenth. 2

Even at the present day, according to Mr. Taylor, the Hindus, at the time of the new year, paint a gammadion in red at the commencement of their account books, and, in their weddings and other ceremonies, they sketch it in flour on the floors of their houses. 3 It also figures at the end of manuscripts of a recent period, at least under a form which, according to M. Kern, is a development of the tétrascèle. 4

The gammadion has been likewise preserved to the present time amongst the Buddhists of Tibet, where the women make use of it in the ornamentation of their skirts, and where it is placed on the

breasts of the dead. 1 In China—where it bears the name of ouan—and in Japan it adorns vases, caskets, and the representations of divinities, as may be seen in the Musée Guimet at Paris; it is even figured upon the breasts of certain statues of Buddha and the Buddhisattvas, where, according to M. Paléologue, it would seem to symbolize the heart. 2 According to another interpretation, given by the Annamite bonzes, it might be the cicatrice of a spear-thrust received by Buddha; but these bonzes, according to M. G. Dumoutier, continue to venerate this symbol without understanding it. 3

In the Woolwich Arsenal the gammadion may be seen upon a cannon captured at the Taku forts by the English. According to M. G. Dumoutier it is nothing else than the ancient Chinese character che, which implies the idea of perfection, of excellence, and would seem to signify the renewal and the endless duration of life. 4 In Japan, according to M. de Milloué, it represents the number 10,000, which symbolizes that which is infinite, perfect, excellent, and is employed as a sign of felicity. 5 A statue of the Buddhisattva Jiso, in the Musée Guimet, rests upon a pedestal ornamented withswastikas.

Lastly let us conclude this long recital, which is in danger of becoming tedious without hope of being complete, by mentioning the presence of thegammadion in Africa, on bronzes brought from Coomassie by the last English Ashantee expedition; 1 in South America, on a calabash from the Lenguas tribe; in North America, on pottery from the mounds and from Yucatan, as also on the rattles made from a gourd which the Pueblos Indians use in their religious dances. 2

Footnotes

33:3 Schliemann. Ilios, fig. 226. See also Troja (English ed.) on an "owl headed" vase of the most recent prehistoric city.

34:2 Perrot and Chipiez. Histoire de l’art dans l’antiquité. Paris, 1885, vol. iii., figs. 513, 515, 518.

34:4 Daremberg and Saglio. Dictionnaire des antiquités des grecques et romaines. Fasc. 12. Paris, 1888. S. v. Diane, p. 153, fig. 2389.

35:1 Numismatic Chronicle. London, vol. viii. (3rd series), p. 103.

35:7 Th. Roller. Les catacombes de Rome, vol. i., pl. vi. 1; pl. x., 29, 30, 31; pl. xxxxii., 15; pl. xxxix., i 9; vol. ii., pl. lv., 2; pl. lxxxviii., 13, and pl. xciv., 2.

36:6 Bulletins de l’Institut archéologique liégeois, vol. x. p. 106.

37:1 It was maintained that these letters signified:—DoMus æterna or D[eo] M[aximo], so that instead of reading, Diis manibus Primus Marci Filius, M. Buckens, formerly Professor at the Academy of the Fine Arts at Liege, did not hesitate, by a free interpretation of the gammadions, the floral ornamentation, the triangle, the niche, and the lotus leaves, to translate them textually as follows: "The last abode of the son of Marcus in Jesus Christ, God, baptized in the name of the Father and of the Holy Ghost"! (Bulletins de l'Institut archéologique liégeois, vol. x. (1870), p. 55.)

38:1 The stone is now in the "Musée du Parc du Cinquantenaire" at Brussels.

38:3 Alex. Bertrand. L’autel de Saintes et les triades gauloises, in the Revue archéologique of 1880, vol. xxxix. p. 343

39:1 Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, vol. xxvii., Feb., 1879. See also the same vol., April, 1879, On the Croix gammée or Swastika.

39:2 R. P. Greg. The Fylfot and Swastika, in Archæologia. London, vol. xlviii., part ii., 1885, p. 298.

39:3 Lud. Müller. Op. cit., passim.—R. P. Greg. Loc. cit., pl. xix., fig. 27, 31, 32, 33.—C. A. Holmboe. Traces du bouddhisme en Norvège. Paris, 1857, pp. 34 et seq.

39:5 Nineteenth Century for June, 1879, p. 1098.

40:1 Ern. Chantre. Recherches archéologiques dans le Caucase. Paris, 1886, vol. ii., atlas, pl. xi., xv., etc.

40:4 Numismatique de l’ancienne Afrique. Copenhagen, 1860–1862, vol. ii. p. 40, No. 4.

41:2 Ramayana.

41:3 Edw. B. Thomas. The early Indian Coinage, in the Numismatic Chronicle, vol. iv. (new series), pl. xi.

41:5 James Fergusson. History of Indian and Eastern Architecture. London. Murray, 1876, p, 184. See our title-page.

42:4 Kern:. Der Buddhismus. Leipzig, 1884, vol. ii. p. 239, note 3.—Colebrooke gives to this sign the name of srivatsa, and makes it out to be the distinctive mark of the tenth Tirthankara of the Jains. M. Schwartz has compared it to the four-leaved clover, which also "brings luck."

43:1 Journal Asiatique, 2nd series, vol. iv. p. 245. Pallas. Samlungen historischer Nachrichten über die mongolischen Volkerschaften, vol. i. p. 277.

43:3 G. Dumoutier. Les Symboles, les Emblèmes et les Accessoires du culte chez les Annamites. Paris, 1891, pp. 19–20.

43:4 G. Dumoutier. Le svastika et la roue solaire en Chine, in the Revue d’Ethnographie. Paris, 1885, p. 331.

43:5 De Milloué. Le svastika, in the Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie of Lyons, 1881, v. i. pp. 191 et seq.

=======================================

II. Different Interpretations of the Gammadion.

That a great number of gammadions have been mere ornaments, monetary signs, or trade-marks, is a fact which it would be idle to dispute. But the uses which have been made of this figure in all the countries which I have just instanced, the nature of the symbols with which it is found associated, its constant presence on altars, tombstones, sepulchral urns, idols, and priestly vestments, besides the testimony of written documents and popular superstitions, afford more than sufficient proof that in Europe as in Asia it partook everywhere of the nature of the amulet, the talisman, and the phylactery. 3 Moreover, for the gammadion to have thus become a charm, it must first of all have been brought into contact with a being, or a phenomenon, more or less concrete and distinct, invested, rightly or wrongly, with some sort of influence on the destiny of mankind. Might it not be possible to rind out this original meaning of the gammadion by laying stress on the indications provided by the monuments themselves?

Many archæologists have thought so, whilst however arriving at different solutions. There is hardly a symbol which has given rise to more varied interpretations—not even the trisula of the Buddhists, which is saying a great deal.

I will confine myself to mentioning the opinion of those who have confounded the gammadion with the crux ansata of the Egyptians, the tau of the Phœnicians, the vajra of India, the Hammer of Thor, or the Arrow of Perkun—all of which are signs having a form and meaning too clearly defined for this identification to be maintained without corroborative evidence. If even the gammadion ever replaced one of them—as in the Catacombs it sometimes takes the place of the Cross of Christ—it only did so as a substitute, as the symbol of a symbol.

Several writers have ascribed a phallic import to the gammadion, some, like M. J. Hoffman, seeing therein the union of the male with the female principle; 1 others, as Sir George Birdwood, believing that they recognize in it especially the symbol of the female sex. 2 The latter supposition would seem to be sufficiently justified by the position assigned to the gammadion on some female idols from the Troad, as also by its association with the image of certain goddesses, the Persian Artemis, Here, Demeter, Astarte. But the gammadion may very well have furnished a symbol of fecundity, as elsewhere a common symbol of prosperity and of salvation, without therefore being necessarily a phallic sign. In the one case, as in the other, the point in question is to ascertain if this is not a secondary meaning, connected with a less abstract conception.

General Cunningham believes that he found in the swastika a Pali monogram formed of four characters corresponding to our letters S. U. T. I. 1 But Professor Max Müller maintains that the likeness is hardly striking, and seems to be purely accidental. 2 In any case, the explanation would apply only to the Indian gammadion; an objection which may likewise be urged against Mr. Frederic Pincott's hypothesis, that the swastika is the emblem of the four castes united in the same symbolical combination. 3

Waring held that the gammadion was a figurative representation of water, on account of its resemblance to the meander, and also of its frequent occurrence in combination with the wavy line, a well-known symbol for water in motion. 4 However, as we shall see further on, this combination is far from being invariable, and certainly the form of the gammadion has, in itself, nothing which conjures up the idea of running water, or of rain.

Others have discerned in it a symbol of the storm, or lightning, because it can be separated into two zigzags or interlaced Z's. W. Schwartz, who, with his usual ability, has upheld this theory,—which conforms with his general views on the meteorological origin of myths and symbols,—draws attention to the numerous points of contact existing between the lightning and the different forms of the Cross not only in the symbolism of many religions, but also in popular language. 5 This agrees with the practice, so common in Catholic countries, of making the sign of the Cross, on the appearance of lightning, to prevent being struck, as also with the custom spread amongst our peasantry, especially in Flemish Brabant, of tracing a Cross in whitewash on their houses to preserve them from the same calamity. But it may be questioned if these customs are not owing to the general talismanic value which the Christian symbol receives in the popular beliefs: the sign of the Cross, in fact, is reputed to drive away evil spirits and to call in divine protection. As for Crosses painted on the outer walls, they seem to be held of use not only against lightning, but also against fires, epidemics amongst cattle, and, generally, against all the unforeseen accidents which threaten the dwelling-place.

In any case there is here no question of the gammadion, and the popular talk about the flashes of lightning "which cross" is not sufficient to account for the derivation of the form of the fylfot. I am well aware that amongst the ancient Germans, and even amongst the Celts, the gammadion is sometimes met side by side with the symbols of thunder on weapons, amulets, ornaments, and even on altars. But these objects present also to our view the image of the Disk, the Crescent, the triscèle, and many other symbolical figures. 1 It would seem as if the engraver had simply wished to bring together all the symbols possessing, to his knowledge, a phylacteric, or talismanic character; by a process of reasoning analogous to that which, in the latter period of Greek paganism, prompted the manufacture of pantheian figures.

M. Emile Burnouf makes the gammadion the symbol of fire, or rather of the mystical twofold arani, that is to say of the fire-drill, which was used to produce fire amongst the early Aryans. "This sign," he writes, "represents the two pieces of wood forming the arani, whose extremities were

curved, or else enlarged, so that they could be firmly kept in place by four nails. At the point where they joined there was a small hole in which was placed the piece of wood, shaped like a spear, whose violent rotation, produced by whipping, made Agni to appear." 1

Up till now it has been by no means proved that the lower part of the arani ever had the form of the swastika or even of the Cross. On the contrary there are reasons for supposing that it was usually a mere log of wood in which the point of the pramantha was made to turn. 2 Perhaps, in some cases, it had a circular form; the fire was then produced by making it revolve round a nave. If, as has been maintained, it really assumed, in some Indian temples, the appearance of the gammadion, it had doubtlessly been given this form to imitate the swastika. 3 As for the four points which are placed between the arms of certain gammadions, there is nothing to prove that they represent nails (see our plate II., litt. B, Nos. 19, 20, 21, 22, and 23), and in most cases they do not even touch the branches of the cross which, according to M. Burnouf, they are intended to fasten. Schliemann, who seems not unwilling to subscribe to M. Emile Burnouf's theory, observes that in Troas the gammadion accompanies the linear drawings of burning altars, 4 but—admitting that these are altars—can they not blaze in the honour of some other god than the fire itself? Further, nothing prevents us from supposing that the sun itself has been represented as a blazing altar.

In support of M. Burnouf's theory, attention might further be called to the fact that the swastika with branches turned towards the right is, amongst the Hindus, accounted of the feminine gender, which would make it agree with the symbolism of the arani. But it must be remarked that the swastikaturned in the other direction passes as masculine. Moreover, according to Sir George Birdwood, it is a common custom in modern India to divide into the two sexes all objects occurring in interdependent pairs.

Mr. R.-P. Greg has written, in the Memoirs published by the Society of Antiquaries, London, a very interesting study on the gammadion, in which, whilst striving to deal impartially with the other explanations of this sign, he contends it is especially a symbol of the air, or rather of the god who rules the phenomena of the atmosphere, Indra with the Hindus, Thor with the ancient Germans and the Scandinavians, Perkun with the Slays, Zeus with the Pelasgians and Greeks, Jupiter tonans and pluvius with the Latin race. 1 Unfortunately, the proofs which he adduces are neither numerous nor conclusive. The fact that in India the bull is sacred to Indra, and that on certain monetary ingots the gammadion surmounts an image of this animal, is hardly sufficient to prove that the swastika is a symbol of Indra. 2 It is likewise difficult to admit that the gammadion represents the god of the atmosphere amongst the Greeks because on some pottery from Cyprus there are gammadions which recall the image of birds flying in the air.

The above-named writer makes much of the fact that on many incised monuments the gammadion is placed above images representing the earth, or terrestrial creatures, and below other images symbolizing the sky, or the sun. But this arrangement is far from being invariable or even predominant. Frequently the gammadion is found on the same level with astronomical symbols; sometimes even it occupies the upper place. Mr. Greg, it is true, gets over the difficulty by asserting that in this case it must represent the god of the ether in the capacity of supreme God. 1

The only example I am acquainted with of a gammadion consecrated to Zeus, or to Jupiter, is on a votive altar, where it is incised above the letters I. O. M. 2 But this is a Celto-Roman altar, erected, to all appearance, by Dacians garrisoned in Ambloganna, a town in Great Britain; that is to say, that here again we may be in the presence of a strange god, assimilated to the supreme divinity of the empire, the Jupiter Optimus Maximus of the Romans. Moreover, the gammadion is here flanked by two four-rayed Wheels, symbols which M. Gaidoz has clearly proved to have been, amongst the Gauls, of a solar character. 3

Lastly, Ludvig Müller, Percy Gardner, S. Beal, Edward B. Thomas, Max Müller, H. Gaidoz, and others, have succeeded, by their studies of Hindu, Greek, Celtic, and ancient German monuments, in establishing the fact that the gammadion has been, among all these nations a symbolical representation of the sun, or of a solar god. I should like here to sum up the respective conclusions of these authors, setting forth, at the same time, the other reasons which have led me, not only to accept, but also to develop their interpretation. This attempt may perhaps be the less superfluous since, judging by the comparatively recent works of M. M. Greg and Schwartz, the solar, or even the astronomical character of the gammadion is not yet beyond dispute.

Footnotes

44:2 T. Lamy. Le svastika et la roue solaire en Amérique, in the Revue d’Ethnographie. Paris, 1885, p. 15.

44:3 M. Michel de Smigrodzki, who in his recent essay, Zur Geschichte der Svastika (Braunschwig, 1890, extracted from the Archiv für Anthropologie), has classified chronologically a considerable number of gammadions belonging to monuments of the most different periods and nations, has made it his special study to show that this cross has everywhere had a symbolical, and not merely an ornamental value.

45:2 Jour. R. As. Soc., v. xviii. (n. s.), p. 408.

46:1 The Bhilsa Topes. London, 1884, p. 386.

46:2 Letter to Schliemann in Ilios, p. 520.

46:3 Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. xix. (n.s.), p. 245.

46:4 Ceramic Art in Remote Ages. London, 1875, p. 13, et seq.

46:5 Der Blitz als geometrisches Gebild, in the Jubiläumschrift der Posener Naturwissenchaft. Verein, 1887, pp. 221–234.

48:3 It is thus the Buddhists have even erected stoupas in the form of the gammadion. (Cf. Schliemann. Ilios, p. 520.)

==============================================

III. Probable Meaning of the Gammadion.

We have seen that most nations represented the sun by a circle. Some, also, have depicted it by a cruciform sign, more particularly the Assyrians, the Hindus, the Greeks, the Celts, etc. (see fig. 2).This symbolism doubtlessly renders the idea of the solar radiation in the four directions of space. But the sun does not restrict itself to darting its rays in all directions, it seems, further, animated by a circular movement from east to west. The latter action may have been symbolized, sometimes by changing the Disk into a Wheel, sometimes by adding to the four extremities of the solar Cross feet, or broken lines, usually turned in the same direction.

Sometimes the curve of the rays was rounded off, perhaps either to accentuate still further the idea of a rotary motion by a figure borrowed from the elementary laws of mechanics, or else by an effect of that tendency, which, in primitive writings, has everywhere substituted the cursive for the angular. Thus was obtained the tétrascèle, which, as I have said above, is simply a variety of the gammadion.

M. Gaidoz has defined the gammadion as a graphic doublet of the Wheel. 1 The expression is exact, and is even a very happy one, provided it means, not that the gammadion is derived from the Wheel by the suppression of a part of the felloe, but that it is, like the Wheel, a symbolical representation of the solar movement.

For the very reason that the gammadion represents the sun in its apparent course it has readily

become a symbol of prosperity, of fecundity, of blessing, and—with the help of superstition—it has everywhere received the meaning of a charm, as in India the very name swastika implies.

Moreover, after having figured the sun in motion, it may have become a symbol of the astronomical movement in general, applied to certain celestial bodies, the moon, for example—or even to everything which seems to move of itself, the air, water, lightning, fire—in as far as it really served as a sign of these different phenomena, which fact has still to be made good. 1—This, in brief, is the whole theory of the gammadion.

This theory is not the outcome of any à priori reasoning; it is founded on the following considerations:

A. The form of the gammadion.

B. The connection between the tétrascèle and triscèle.

C. The association of the gammadion with the images, symbols, and divinities of the sun.

D. The part it plays in certain symbolical combinations, where it sometimes accompanies and sometimes replaces the representation of the solar Disk.

A. The branches of the gammadion are rays in motion.

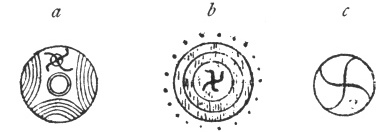

To be convinced of this, it is only necessary to cast one's eyes on the manner in which, at all times, the idea of solar movement has been graphically expressed (fig. 22).

The first of these figures (a) is an ancient fibula found in Italy. At the top is seen a Disk from which radiate small rays, bent at right angles; these rays seem to have been modelled on the

branches of the gammadions sketched immediately beneath.

The second (b) is taken from the "whorls" of Troy. Crooked rays, turned towards the right, alternate with straight and undulating rays, all of which proceed from the same Disk.

The third (c) comes from a reliquary of the

Fig. 22. 1

thirteenth century, on which it forms a pendant to the lunar crescent, with an image of Christ between them. That this is a representation of the solar Disk results not only from its parallelism with the Crescent, but also from the fact that on a number of mediæval Christian monuments Christ is thus represented between the sun and moon. 2The same image—a Disk with five inflected rays—is met with on coins of Macedon (d), where it alternates sometimes with the tétrascèle (e).

Mr. Samuel Beal, who distinguishes two parts in the gammadion,—an equilateral cross and four hooks,—thinks that the purpose of the former is to symbolize the earth; as for the hooks, they might serve to indicate the direction of the solar movement round our planet. 3 But the figures which

we have reproduced here give more than sufficient proof that the arms of the gammadion, if they are solar rays, are so in their whole length; besides, the Disk which sometimes forms their point of intersection is certainly an image of the sun; lastly, there is no indication that, either in classic antiquity, or in India, the earth was ever symbolized by an equilateral cross.

B. The triscèle, formed by the same process as the tétraskèle, was an undeniable representation of the solar movement.

This assertion is especially obvious in the case of triskèles formed of three legs bent, as in the

Fig. 23. Varieties of the Triscèle. 1

act of running, so frequently seen on coins of Asia Minor.On Celtiberian coins the face of the sun appears between the legs. The same combination is found, above the image of a bull, on a votive stele of Carthage, reproduced by Gesenius. 2

Is it possible to better interpret the idea of motion, and of its application to the image of the sun?

I will further instance the coins of Aspendus, in Pamphylia, where the three legs, ranged round a

central disk, are literally combined with animal representations of the sun, the eagle, the wild boar, and the lion. 1 Lastly, on certain coins of Syracuse the triscèle permutes with the solar Disk above the quadriga and the winged horse. 2

Moreover, the connection between the triscèle and the tétrascèle is manifest from their very shape. The transition from one to the other is visible on the "whorls" of Troy as well as on coins of Macedon and Lycia.

Fig. 24. Symbols On Lycian Coins.

(Ludvig Müller, figs. 48 and 49.)

C. The images oftenest associated with the gammadion are representations of the sun and the solar divinities.(Ludvig Müller, figs. 48 and 49.)

Greek coins often show, side by side with the gammadion, the head of Apollo, or the reproduction of his attributes. On a piece from Damastion, in Epirus, the gammadion is engraved between the supports of the Delphic tripod; 3 on painted vases from Rhodes and Athens it figures beside theomphalos. 4 A crater in the Museum of Ancient Art in Vienna shows an image of Apollo bearing it on his breast (see our Plate I.); on a vase from Melos it precedes the chariot of the god. 5 Even amongst the Gauls it accompanies, on coins, the laurelled and nimbus-encompassed head of Apollo Belenus. 1 To be sure, it is also found on Greek medals associated with the images of Dionysos, Hercules, Hermes, and of several goddesses. But, in addition to the explanations of this peculiarity which I have given, it must be borne in mind how readily polytheistic nations and cities assign to their principal god the emblems as well as the attributes of other divinities—witness, in classic antiquity, the use of the Caduceus, the Thunderbolt, the Cornucopia, and so forth.

Amongst the symbols accompanying the gammadion there is none nearly so frequent as the solar Disk. The two signs are, in a manner, counterparts, not only amongst the Greeks, the Romans, and the Celts, but also with the Hindus, the Japanese, and the Chinese. I have already given some examples (figs. 17, 18, 20). On a "whorl"

Fig. 25. Whorl from Hissarlik.

(Schliemann. Ilios, No. 1990.)

from Hissarlik this parallel order is repeated three times.(Schliemann. Ilios, No. 1990.)

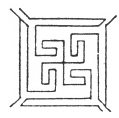

Fig. 26. 2

Sometimes, as if to accentuate this juxtaposition, the gammadion is inscribed in the disk itself.Sometimes, on the contrary, it is the solar Disk which is inscribed in the centre of the gammadion, as may be verified particularly on a Tibetan symbol reproduced by Hodgson, 1 and also on a coin from Gnossus, in Crete, where, perhaps, it depicts the Labyrinth.

Fig. 27. Cretan Coin.

(Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (new series), pl. iii., No. 6.

On a Gallic coin, of which numerous specimens have been found in the Belgian province of Limburg and in the Namur country, a tétrascèle is visible, formed by four horses' heads ranged in a circle round a Disk.(Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (new series), pl. iii., No. 6.

Fig. 28. Gallo-Belgian Coin.

(Hucher. L’art gaulois, p. 169.)

It is impossible not to recognize here an application of solar symbolism, as M. Eug. Hucher has so frankly admitted, in language whose terms exclude all preconceived ideas upon the solar nature of the tétrascèle, or even on the affinity existing between the Gallic symbol and the gammadion: "These four busts of horses," he writes, "are evidently the rudiments of the four fiery steeds which draw the chariot of Helios in Etruscan and Greek antiquity. But the fact cannot be ignored that the gyratory arrangement, not in use amongst the Greeks, is a product of the Celtic imagination." 1(Hucher. L’art gaulois, p. 169.)

What, perhaps, is the product of the Celtic imagination, is the ingenious transformation of the arms of the gammadion into horses’ busts. Would it not be possible to find in Greek symbolism precedents, and even models for this metamorphosis?—witness the cocks’ heads and lions’ busts which take the place of the rays of the triscèle on Lycian coins. 2

We may observe, by the way, that the horse, and the cock, as well as the eagle, and the lion, are essentially solar animals.

It is interesting to verify the fact that the same combination has been produced, doubtlessly through the spontaneous agency of similar factors, in Northern America. There have been found,

Fig. 29. Engraved Shell from the Mississippi Mounds.

(Holmes. Bureau of Ethnology, vol. ii., p. 282.)

amongst the engraved shells of the mounds or tumuli of the Mississippi, several specimens of solar Crosses inscribed in circles, or squares, each side forming a support to a bird's head turned in the same direction—which, as a whole, forms a veritable gammadion.(Holmes. Bureau of Ethnology, vol. ii., p. 282.)

D. In certain symbolical combinations the gammadion alternates with the representation of the sun.

Edward Thomas has pointed out the fact that, amongst the Jains of modern India, the sun, although held in great honour, does not appear amongst the respective signs of the twenty-four Tirthankaras, the saints or mythological founders of the sect. But, whilst the eighth of these personages has the half-moon as an emblem, the seventh has the swastika for a distinctive sign. 1 Moreover, as the same writer remarks, the swastika and the Disk replace constantly each other on the ancient coins of Ujain and Andhra.

Another proof of the equivalence between the gammadion and the image, or, at least, the light of the sun, is found amongst the coins of Mesembria in Thrace. The very name of this town, Μεσημβρία, may be translated as "mid-day," that is, the "town of noon," as Mr. Percy Gardner calls it. 2 Now, on some coins, this name is figured by a legend which speaks for itself:

It is impossible to show more clearly the identity of the gammadion with the idea of light or of the day.—"But," objects Mr. Greg, "the day is not necessarily the `sun."—In addition to this distinction being rather subtle, how can one continue to doubt, in face of the facility with which in Greece, as in India and elsewhere, the gammadion interchanges with the Solar Disk and vice versa? 3

I will take the liberty of calling attention to the adjoining plate (II.), where I have brought together several peculiar examples of those transpositions. They are arranged in two classes of combinations, which, by their regularity no less than by their frequency, seem to imply a symbolical intention. In the first is visible a grouping together of three signs gammadions, or Disks, round the one central Disk; in the second it is these same signs, to the number of four, which are arranged in a square or lozenge, either round a fifth analogous sign, or else, between the branches of an equilateral cross. I should here like to attempt, in connection with the general meaning of the gammadion, an explanation of these symbolical arrangements—in so far, of course, as on certain Disks these signs are not merely ornaments, intended to fill up the empty spaces.

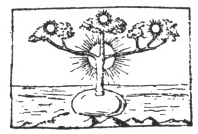

The three first numbers of the first combination (litt. A) are taken from the "whorls" of Hissarlik; 1 the fourth from a sepulchral vase from Denmark; 2the fifth from Silesian pottery; 3 the sixth, which represents a foot-print of Buddha, from the bas-reliefs of Amaravati; 4 the seventh, a curious example of the trisula, from the Græco-Buddhist sculptures of Yusufzaï, in North-western India. 5 To these must be added, on the following page, the image taken from Hindu symbols and reproduced by Guignaut, after Nicolas Müller.

It is this latter figure which will assist us in explaining the others, or, at least, in formulating a conjecture as to their signification.

The subject is a tree, standing apparently for the Cosmic Tree of Hindu mythology, which sprang

from the primordial egg in the bosom of the chaotic ocean. It spreads out into three branches, each of which supports a sun, whilst a fourth and

Fig. 30. Hindu Symbol.

(Guignaut, vol. iv., 2nd part, pl. ii., fig. 16.)

larger sun is placed at the bifurcation of the branches.(Guignaut, vol. iv., 2nd part, pl. ii., fig. 16.)

Guignaut informs us, in his translation of Creuzer, that this image was a symbol of the trimurti, the Hindu Trinity. We need not here investigate this very questionable proposition. I think, however, that the learned Frenchman was right when he added, in a foot-note:—"There are here three suns, and yet it is always the same sun." 1

In reality might not the object of this combination be to represent the sun in the three points or positions which circumscribe its apparent daily course, its rising, its zenith, and its setting; which the figurative language of Vedic mythology has rendered by the Three Steps of Vishnu?

We know that at all times popular imagery, in order to represent movements, or changes of position, has resorted to the artifice of multiplying the image of the same personage, or object, whilst assigning to it a different attitude each time. It is the process of juxtaposition applied to the idea of succession, or, as M. Clermont Ganneau has expressed it: "The reappearance of the actors to mark the succession of the acts." 2 Do we ourselves represent otherwise, in our astronomical diagrams, the phases of the moon, or the different positions of the sun in the ecliptic?

The same meaning seems to me to be applicable to the three swastikas incised round a Disk on a Foot-print of Buddha . In fact, Buddha's Feet were originally the Feet of Vishnu; Buddhism was content to attribute to the footsteps of its founder the marks already worshipped by Hindu tradition. 1 The other signs which adorn this mark seem to singularly complicate its symbolism. But it must not be forgotten that the Buddhists have accumulated, on the sacred Foot of their Master, almost all the symbols they have been able either to invent or borrow. Tradition counts as many as sixty-five! Moreover, most of these signs are also solar symbols, at least the Rosettes, the Trident, and the trisula, the latter representing, as I shall hereafter show, the effulgence, or the radiation of the solar fire.

Edward Thomas has fully admitted that there must be some connection between the three diurnal positions of the sun and the incised symbols on the foot-print at Amaravati. But if, in the central Disk, he discerns the noon-day sun, it is the trisula, on the heel, which seems to him to represent the rising sun, whilst the swastikas depicted on the toes might typify the last rays of sunset. As for the other swastikas, the two signs on the heel might symbolize the Asvins, the third, the god Pûshan.—For my part, I see nothing which can justify these latter comparisons. Mr. Thomas was more fortunate when he connected an image, taken by Sir Henry Rawlinson from an obelisk at Koyunjik, with the Hindu symbolism relating to the three positions of the sun. 2 Three solar Disks are there represented side by side; the middle one sends forth straight rays, and a hand holding a bow (see above, fig. 11); the two others, of rather smaller dimensions, emit rays which are bent at the extremities, as if by an effect of centrifugal force. 1

This interpretation may be further applied to the three Wheels placed on the points of the trisula in a Græco-Buddhist bas-relief of Yusufzaï (litt. A, No. 7). If, as I believe I shall prove, 2 the central Disk of the trisulas was an image of the sun before it became, with the Buddhists, the Wheel of the Law, as much may be said of the three Wheels which here crown the points of the ancient symbol.

In Greece, I am not aware that the mythology alludes to the "three strides" of the sun. But symbolical images sometimes take the place of figures of speech. Does not, for example, the triscèle, formed of three legs radiating round a disc, admit of the same interpretation as the Hindu tree with its four suns? There is, moreover, presumptive evidence that the Greeks distinguished three positions of the sun, and even that they selected distinct personages to represent those principal moments of its daily life. Near Lycosura, in Arcadia, stood the sanctuary of Zeus Lycæus, where, according to Pausanias, bodies cast no shadow. It was situated on a mountain between two temples, one, to the east, was sacred to the Pythian Apollo, the other, towards the west, was dedicated to Pan Nomios. 1 Apollo, the slayer of the Python, well represents the morning sun dispelling the darkness in the east. As for the Lycæan Jupiter of Arcadia, it is the sun in all its mid-day glory, at the hour when bodies cast the least shadow. 2 Lastly, Pan, the lover of Selene, has incontestably a solar character, or at least is connected with the sun when setting. M. Ch. Lenormant has brought into prominence the light-giving character of this divinity, whom Herodotus compares, without hesitation, to Chem or Min, an Egyptian personification of the nocturnal or subterranean sun. 3

Our own popular traditions seem also to have preserved the remembrance of the three solar steps, at least in those parts of Germany and England where, till lately, the villagers climbed a hill on Easter-eve, in order to perform three bounds of joy at sun-rise. "And yet," adds Sir Thomas Browne, "the sun does not dance on that day." 4 It must be remarked that popular language still speaks of the "legs of the sun," referring to those rays which sometimes seem to move about on the ground when their focus is hidden behind a cloud.

Let us now pass to the second group (pl. ii., litt. B), which represents combinations of four secondary figures ranged round a central one. 1 I will here venture—always by way of hypothesis—an explanation similar to the preceding ones. Equilateral crosses representing the sky, or the horizon, have been found on Assyrian monuments. Their extremities are sometimes ended by little disks,

2 It may be questioned, not only whether these disks do not represent so many suns, as is the case in the preceding combinations, but also whether they do not relate to four different positions of the luminary, which would, perhaps, suggest no longer its daily course, but its annual revolution, marked by the solstices and equinoxes.

2 It may be questioned, not only whether these disks do not represent so many suns, as is the case in the preceding combinations, but also whether they do not relate to four different positions of the luminary, which would, perhaps, suggest no longer its daily course, but its annual revolution, marked by the solstices and equinoxes.However this may be, the symbol of four Disks united by a Cross, spread, as a subject of decoration, through Asia Minor, Greece, Italy, and India, being sometimes simplified by the substitution of a central Disk for the Cross (pl. ii., litt. B, Nos. 9 to 13), sometimes complicated by the introduction of the gammadion (Nos. 8, 16, and 18 to 23), without counting the variations produced by

the partial or general transpositions of the Disks and gammadions. No. 17 represents a Cross whose gamma character results precisely from the addition of a Disk to the right of each arm. Nos. 14 to 18 may be considered as forming a transition to the symbols 19, 20, 21, 22, and 23, where it is no longer the gammadion which is inscribed in or alongside the Disks, but where the Disks themselves are placed between the branches of thegammadion. Perhaps also the combinations reproduced at the bottom of the plate may come directly from the equilateral cross, with disks placed between the branches

. The latter, after having ornamented Hissarlik pottery and the most ancient coins of Lydia, was preserved even on the coins and coats of arms of the Christian Middle Ages, its intermediate stages being the pottery of the "palafittes" in Savoy, and, later, the numerous Gallic coins on which the disks between the arms are sometimes changed into Wheels and Crescents. 1

. The latter, after having ornamented Hissarlik pottery and the most ancient coins of Lydia, was preserved even on the coins and coats of arms of the Christian Middle Ages, its intermediate stages being the pottery of the "palafittes" in Savoy, and, later, the numerous Gallic coins on which the disks between the arms are sometimes changed into Wheels and Crescents. 1In these four disks or points, Mr. Greg discerns stars or small fires. 2 I wonder what fires would be here for. We might as well accept the four nails of Emile Burnouf. I much prefer to believe that, in conformity with the usual interpretation of the Disk, they were originally representations of the sun; and do not these suns, perhaps, represent, to use Guignaut's expression, "always the same sun" at a different point of the celestial horizon?

The theory that the gammadion symbolizes the sun's motion, has met with the objection that the ancients were not acquainted with the rotation of the sun on its own axis. But, properly speaking, there is here no question of a rotatory motion.

What they wished to denote in bending the rays of the disk, was the circular translation in space which the sun seems to undergo during the day, or the year. The proof of this is found in the symbolism of the Wheel, which likewise served to represent the progress of the sun, without, for that reason, implying a knowledge of the solar rotation.

An ancient rite, occurring in different branches of the Indo-European family, consisted in making the circuit of the object intended to be honoured, or sanctified, keeping, meanwhile, the right side turned towards it, that is to say, following the apparent direction of the sun. Known in India by the name of pradakshina, and still practised by the Buddhists of Tibet round their sacred stones, this custom has survived to our own times in different parts of Europe. Dr. MacLeod relates that the Highlanders of Scotland, when they came to wish his father a happy New Year, made in this manner the circuit of the house, in order to ensure its prosperity during the year. At St. Fillans, by Comrie, in Perthshire, this circumambulation, called deasil(deisul), was performed round a miraculous well, to which people came in search of health. A similar custom seems to have existed in the Jura Mountains. 1

Another objection is, that a certain number of gammadions have their branches turned towards the left, that is to say, in the opposite direction to the apparent course of the solar revolution. 2 Prof. Max Müller has remarked that, perhaps, in this case, it was intended to represent the retrograde motion of the autumnal sun, in opposition to its progressive movement in the spring. 3 Unfortunately,

the eminent Indian scholar produces no evidence in support of this hypothesis. 1 Would it not be simpler to admit that the direction of the branches is of secondary importance in the symbolism of the gammadion? When it was desired to symbolize the progress of the sun, namely, its faculty of translation through space, rather than the direction in which it turns, little attention will have been paid to the direction given to the rays. Although, in general, the form of the swastika predominates, the branches are turned towards the left in a great number of gammadions or tétrascèles which are undeniably connected with the personifications or the symbols of the sun. 2 The same peculiarity may, moreover, be remarked on triscèles whose solar character is not disputed, 3 and even on direct images of the sun, such as Disks whose rays, bent in order to render the idea of motion, are turned towards the left as well as towards the right. 4 Lastly, it sometimes happens that the same monument includes several gammadions whose branches are turned respectively in the opposite direction. 1 Tradition, as we have seen, counts the two forms among the signs of good omen which adorn the feet of Buddha. The Musée Guimet possesses two statues of Buddha decorated with the gammadion, one, of Japanese manufacture, bears the swastika; the other, of Chinese origin, the sauwastika.

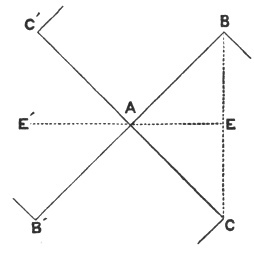

I must here call attention to an ingenious theory brought forward, in 1891, by M. E. Harroy, director of the Ecole moyenne de Verviers, at the Archæological and Historical Congress of Brussels, to account for the origin of the gammadion, and its connection with the equilateral cross. 2 He believes he has discovered, in the arrangement of certain cromlechs, indications which would point to their having formed a sort of astronomical dial, as exact as it was primitive. For its construction

he only requires three stones. At twenty paces from a point of observation, A, let us place, he says, a stone, B, in the direction in which the sun rises on the 21st of June; then at the same distance

from A place a second stone, C, in the direction in which the sun rises on the 21st of December.

The line B C will point north and south; A E east, and A E´ west. A B, A E, A C, and A E, will give the directions in which the sun rises on the 21st of June, the 21st of September, the 21st of December, and the 21st of March respectively; A C´, A E´, A B´, and A E´, the directions in which it will set on the same dates. This cross, illustrating the course of the sun, will naturally become the symbol of the luminary, and four strokes might have been added to the extremities of the lines in order to give "the notion of impulsion of the rotatory movement of the regulating orb."

I will draw attention to the fact that, as the points B and C approach or go further apart, according to the latitude, this figure can only depict a cross in a fairly narrow zone of the terrestrial globe, and that, consequently, the explanation of M. Harroy is solely applicable to our latitudes. Even here, moreover, however simple the reasoning processes are which might have led to the construction of this natural observatory, there remains to be proved satisfactorily that such an idea was ever entertained and put into practice by our prehistoric ancestors.

I have admitted above that the gammadion, in so far as it was a symbol of the astronomical movement, may have been applied to the revolutions or even to the phases of the moon. The fact is all the more plausible since the equilateral cross seems itself to have been employed to symbolize lunar as well as solar radiation; if we may judge from a Mithraic image, where the points of the Crescent supporting the bust of the lunar goddess are each surmounted by an equilateral cross. 1 In this manner the frequent attribution of the gammadion to lunar goddesses, such as the different forms of the Asiatic Artemis, might also be accounted for.

On coins of Gnossus, in Crete, the lunar Crescent

Fig. 32. Cretan Coin.

(Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx., new series, pl. ii., fig. 7.)

takes the place of the solar Disk in the centre of the gammadion.(Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx., new series, pl. ii., fig. 7.)

A coin, which is believed to belong to Apollonius

Fig. 33. Lunar Tétrascèle.

(Barclay V. Head. Numismatic Chronicle, vol. vii. (3rd series), pl. xi., fig. 48.)

ad Rhyndacum, shows a gammadion flanked by four Crescents.(Barclay V. Head. Numismatic Chronicle, vol. vii. (3rd series), pl. xi., fig. 48.)

On the sepulchral stelai of Numidia the two gammadions surmounting the image of the dead (see our fig. 17, where one of them is, so to speak, underlined by a Wheel) may be seen to give place, sometimes to two radiated Disks, sometimes to a Wheel and a Crescent, sometimes to an equilateral Cross and a Crescent, and, lastly, sometimes to two Crescents. 1 From which it might be concluded that the gammadion serves equally to replace the image of the sun and that of the moon.

M. Schliemann found at Hissarlik, in the strata lying above the "burnt city," a terra-cotta sphere divided into parallel zones by horizontal lines. In the middle zone are thirteen gammadions drawn up in line side by side. The celebrated explorer of Ilium believed he discovered therein a terrestrial sphere, on which the gammadions, symbols of fire, seemed to indicate the torrid zone. Mr. R. P. Greg, faithful to his theory, prefers to discern therein a representation of the universe, where theswastikas would seem to symbolize the supreme power of Zeus. 1 May I be allowed to ask, in my turn, if there may not be seen herein a celestial sphere, on which the thirteen gammadions represent thirteen moons, that is to say, the lunar year?

Fig. 34. Fusaïole Or Whorl From Ilios.

(Schliemann. Ilios, figs. 245 and 246.)

(Schliemann. Ilios, figs. 245 and 246.)

Footnotes

51:1 H. Gaidoz. Op. cit., p. 113.52:1 "On a terra-cotta from Salamine, representing a tethrippos or four-wheeled chariot, a gammadion is painted on each quarter of the wheel."—Cesnola, Salamina, London, 1832, fig. 226.

53:1 a. Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques. Reports of the Copenhagen Session, 1875, p. 486. b. Schliemann.Ilios, No. 1993. c. On a reliquary from Maestricht in the Museum of Antiquities in Brussels, No. 24 in catalogue. d and e. On coins from Macedon.Numism. Chronicle, vol. xx. (N. S.), pl. iv., Nos. 6 and 9.

53:2 The same figure, separated from the lunar crescent by the cross, is met with on a sculpture at Kelloe in Durham. (On a sculptured cross of Kelloe, in Archæologia, vol. lii., part i., p. 74.)

53:3 Indian Antiquary, 1880, p. 67 et seq.

54:1 a. On a coin from Megara (Percy Gardner, Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (N. S.), p. 60). b. On a Lycian coin (Fellows, Coins of Ancient Lycia. London, 1855, pl. x.). c. On a Lycian coin (Numism. Chron., vol. viii. (3rd series), pl. v., No. 1). d. On a Celtiberian coin (Lud. Müller, fig. 46).

54:2 Gesenius. Scripturæ linguæque Phœnicæ monumenta. Leipsic, tab. 23.

55:1 Barclay V. Head. Hist. num., p. 581.

55:2 Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (new series), pl. iii., figs. 1 and 3.

55:3 Numismata cimelii regii Austriaci. Vienna, 1755, part i., tab. viii., No. 3.

55:4 J. B. Waring. Ceramic Art in remote Ages. London, 1875, pl. xxvii., f. 9.

55:5 J. Overbeck. Atlas der griechischen Mythologie, Apollon, pl. xix., fig. 7.

56:1 Lud. Müller. Op. Cit., fig. 27.

56:2 a. On a "fusaïole" from Hissarlik. Schliemann. Ilios, p. 57 No. 1987. b. On a Celtic stone of Scotland. R.-P. Greg, Archæologia, 1885, pl. xix., fig. 27. c. On an ex voto of clay in the sanctuary at Barhut. Numism. Chron., vol. xx. (new series), pl. ii., fig. 24. See also below, pl. ii., litt. B, No. 16.

57:1 See below, No. 18, litt. B of pl. ii.

58:1 Eug. Hucher. L’art gaulois. Paris, 1868, vol. ii., p. 169.

58:2 See below, chap. v., figs. 89, 90, 91.

59:1 Indian Antiquary, 1881, pp. 67, 68.

59:2 Percy Gardner. Solar Symbols on the Coins of Macedon and Thrace, in the Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (N. S.), p. 59.

59:3 Ibid. Loc. cit., pp. 55–58.—On coins from Segesta the gammadion, which surmounts the image of a dog, alternates with a four-spoked wheel. (Hunter, pl. xlviii., 4, and lvii., 5.)

60:1 Schliemann. Ilios, Nos. 1951, 1947, and 1861.

60:2 Lud. Müller. Op. cit., fig. 31.

60:3 Ibid. Op. cit., fig. 30.

60:4 James Fergusson. Eastern and Indian Architecture. London, p. 184.

60:5 Græco-Buddhist sculptures of Yusufzaï, in the publication Preservation of National Monuments of India, pl. xxi.

61:1 Guignaut. Les religions de l’antiquité. Paris, 184r, vol. iv., first part, p. 4.

61:2 See Clermont-Ganneau. L’imagerie phénicienne, p. 10.

62:1 Senart. La légende du Bouddha in the Journal asiatique. Paris, 1873, vol. ii., p. 278, and 1875, vol. ii., pp. 120, 121.

62:2 Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx. (N. S.), pp. 31, 32.

63:1 Foot-prints have been used more than once as a vestige of presence, a testimonial of passage, a symbol of walking. One finds them on stones dedicated to Isis and to Venus, in the latter days of the Roman empire, where, according to Letronne's interpretation, they are equivalent to the well-known inscription, ἦλθα ἐνταῦθα, "I have been here." When the soles of both feet point each in an opposite direction, they may imply the idea of going and returning, a symbol of gratitude to the gods for a safe journey, "Pro itu ac reditu felice."—On Christian tombstones of the same epoch they sometimes are accompanied by the words In Deo, meaning, perhaps, "Walked into God." (See Raoul Rochette, Sur les peintures des Catacombes dans les Mémoires publiés par l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, t. xiii., p. 235.)

63:2 See further, chap. vi.

64:1 Pausanias, VIII., 38.

64:2 A. Maury. Religions de la Gréce antique. Paris, 1857, vol. i., p. 59.

64:3 Ch. Lenormant. Galerie mythologique in the Trésor de numismatique. Paris, 1850, p. 25.

64:4 E. B. Tylor. Civilisation primitive, vol. ii., p. 385.

65:1 Nos. 8, 9, 12, and 19 are taken from Hissarlik pottery (Schliemann. Ilios, No. 1218, 1873, 1958, and 1822); No. 10, from a cup from Nola (Lud. Müller, fig. 18); No. 11, from an archaic Athenian vase (Id., fig. 7); No. 13 from a cylinder of Villanova (De Mortillet. La croix avant le christianisme. Paris, 1866, fig. 39); No. 14, from a coin of Belgian Gaul (Revue numismatique. Paris, 1885, pl. vi., No. 4); Nos. 15 and 16, from ancient Indian coins (A. Cunningham. Bhilsa Topes. London, 1854, pl. xxxi., figs. 3 and 4); No. 17, also from an ancient Hindu coin (Greg.Archæologia, 1885, pl. xix., fig. 29); No. 18, from Buddhist symbols of Tibet (Hodgson. Buddhist Symbols in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. xviii., 1st series, pl. i., fig. 20); No. 20, from an earthenware vessel of Santorin (Waring. Ceramic Art in Remote Ages, pl. xliii., fig. 2); No. 21, from a coin of Macedon (Numismatic Chronicle, vol. xx., new series, pl. iv., No. 7); No. 22, from the bas-reliefs of Amaranati (cf. above, litt.A, No. 6); lastly, No. 23, from a girdle of bronzed leaves found in a tumulus of Alsace (De Mortillet. Musée préhistorique, pl. c., No. 1235).

65:2 Victor Duruy. Symboles païens de la croix, in the Revue politique et littéraire, 14th January, 1882, p. 51, fig. 8.

66:1 L. Maxe Werly. Monnaies à la croix, in the Revue belge de Numismatique. Brussels, 1879, pl. xii. and xiii.

66:2 Greg. Loc. cit., p. 296.

67:1 Sir John Lubbock. Origin of Civilisation. London, 1870, pp. 214 and 226.

67:2 F. Pincott, in the Journal of the Roy. Asiat. Soc., vol. xix. (new series), p. 245.

67:3 Letter to M. Schliemann. Ilios, p. 520.

68:1 However, in the last edition, recently published, of the Report on the Old Records of the India Office (London, 1891, pp. x–xi), Sir George Birdwood makes mention of, the fact that the "right-handed" swastika is, with the Hindus, the emblem of the god Ganesh; that it represents the male principle; that it typifies the sun in its daily course from east to west, and that, lastly, it symbolizes light, life, and glory. The "left-handed" swastika, orsauwastika, on the contrary, is the emblem of the goddess Kali; it represents the female principle, typifies the course of the sun in the subterranean world from west to east, and symbolizes darkness, death, and destruction.

68:2 Such, for example, are the gammadions inscribed between the supports of the tripod of Apollo on a coin of Damastion mentioned above, and the gammadion on the breast of an Apollo reproduced in our plate i.

68:3 P. Six, in the Revue de Numismatique. Paris, 1886, P. 147.

68:4 Percy Gardner. Numism. Chron., vol. xx., pl. iv. No. 20.

69:1 Th. Roller. Les catacombes de Rome, vol. i., pl. vi., 1.—Cf. certain disks on the Hissarlik whorls. (Schliemann. Ilios, No. 1951.)

69:2 Proceedings of the Congrès archéologique et historique of Brussels, vol. i. Brussels, 1892, pp. 248–250.

70:1 Lajard. Atlas, pl. lxxviii.

71:1 Stèles du Koudiat el Batoum, in the Comptes rendus de la Société française de numismatique et d’archéologie, vol. ii., pl. iii, figs. 1 to 6.

=============================================

IV. The Birth-Place of the Gammadion.

Can we determine the cradle of the gammadion, or, at least, the region whence it sprang, to be transported to the four corners of the Old World? To be sure, it may have been formed spontaneously here and there, in the manner of the equilateral crosses, the circles, the triangles, theflower-mark, and the other geometric ornaments so common in primitive decoration.

But the specimens which we have been examining are too identical, in their meaning as in their use, for us not to admit the original unity of the sign, or, at the very least, of its symbolical meaning.

A first observation, made long ago, is that the gammadion is almost the exclusive property of the Aryan race. It is found, in fact, among all the peoples of the Indo-European branch, whilst it is completely absent among the Egyptians, the Chaldæans, the Assyrians, and even the Phœnicians, although these latter were not very scrupulous in borrowing the ornaments and symbols of their neighbours. As for the Tibetans, the Chinese, and the Japanese, amongst whom it is neither less frequent nor less venerated, it is not difficult to prove that it must have come to them, with Buddhism, from India.

There was only a step from this to the conclusion that the gammadion is a survival of the symbolism created, or adopted, by the common ancestors of the Aryans, and this step has been easily got over. Had we not the precedents of philology, which cannot come upon the same radical in the principal dialects of the Indo-European nations without tracing its existence to the period when these people spoke the same language? We did not even stop there. Desirous of investing the gammadion with an importance proportioned to the high destiny imputed to it, one has endeavoured to make it the symbol of the supreme God whom the Aryans are said to have adored before their dispersion. Thus we have seen Mr. Greg exhibit the gammadionas the emblem of the god of the sky, or air, who, in the course of the Indo-European migrations, was converted into Indra, Zeus, Jupiter, Thor, and so forth. M. Ludwig Müller, on his side, after having by his very complete and conscientious work on the gammadion contributed so much to proving it to be a solar symbol, takes care to add that before receiving this signification it might well have been, with the primitive Aryans, "the emblem of the divinity who comprehended all the gods, or, again, of the omnipotent God of the universe."

To this end he draws attention to the fact that the gammadion is associated with divinities of different nature, and that, therefore, it might well have the value of a generic sign for divinity, in the manner of the Star which figures before the divine names in the cuneiform inscriptions of Mesopotamia: "The sign," he concludes, "expressed then figuratively the word θεός, which corresponded with deva, from which it is derived; it is thus the primitive Aryans called the divinity whose symbol this sign probably was." Who knows if it did not imply and retain a still higher signification; if, for example, the Greeks, "following the Pelasgians," did not employ it to symbolize a god elevated above the Olympians, or even the One and Supreme Being of philosophy arid religious tradition, "the unknown God, to whom, according to Saint Paul, an altar was dedicated at Athens"? 1

This is doing great honour to the gammadion. To reduce these theories to their real value it is only necessary to show that they are conjectures with no foundation in history. When the latter begins to raise the veil which conceals the origins of the Greeks, the Romans, the ancient Germans, the Celts, the Slays, the Hindus, and the Persians, we find these nations adoring the vague numina of which they caught a glimpse behind the principal phenomena of nature, worshipping the multitude of spirits, and indulging in all the practices of inferior religions, with here and there outbursts of poetry and spirituality which were as the promise and the dawn of their future religious development.

It is probable that before historic times they had already fetiches, perhaps even idols, in the manner of those uncouth xoana which are met with in the beginnings of Greek art. But it is unlikely that at the far more distant epoch of their first separation they had already possessed symbols, that is to say, ideographic signs, figures representing the divinity without aspiring to be its image or receptacle. In any case we may here apply the adage affirmantis onus probandi; upon those who wish to make the gammadion a legacy of the "primitive" Aryans, it is incumbent to prove that these Aryans practised symbolism; that amongst their symbols the gammadion had a place, and that this gammadion typified the old Diu pater, the Heavenly Father of subsequent mythologies.

Should the same criticism be extended to the theories which make the gammadion a Pelasgic symbol,—whether by Pelasgians be understood the Western Aryans in general, or merely the ancestors of the Greeks, of the ancient Italians, and of the Aryan populations who, primitively, fixed their residence in the basin of the Danube?

We can here no longer be so affirmative in our negations. It is, indeed, an undeniable fact that the gammadion figures amongst the geometric ornaments on certain pottery styled Pelasgic, because, in the bronze period, or the first iron age, it is found amongst all the Aryan peoples, from Asia Minor to the shores of the Atlantic. 1 But, to begin with, the very term Pelasgian does not seem to me a happy one, and it may be noted that there is now a tendency amongst archæologists to drop it. This term either refers to the pre-Hellenic, and the pre-Etruscan phase of civilization in the South of Europe, when it is only a word designed to hide our ignorance, or else it claims to apply to a determinate people, and then it confounds under the same denomination very different populations, of whom nothing authorizes us to make an ethnic group. Moreover, in so far as the first appearances of the gammadion are concerned, it is possible, and even necessary, to limit still further our geographical field of research.

Without going into the question whether geometric decoration may not have originated in an independent manner amongst different nations, it must be observed that this style of ornamentation embraces two periods, that of painted and that of incised decoration. Now, in this latter period, which is everywhere the most ancient, the gammadion is only found on the "whorls" of Hissarlik and the pottery of the terramares. We have here, therefore, two early homes of our symbol, one on the shores of the Hellespont, the other in the north of Italy.

Was it propagated from one country to another by the usual medium of commerce? It must be admitted that at this period the relations between the Troad and the basin of the Po were very doubtful. Etruria certainly underwent Asiatic influences; but whether the legendary migration of Tyrrhenius and of his Lydians be admitted or not, this influence was only felt at a period subsequent to the "palafittes" of Emilia, if not to the necropolis of Villanova.

There remains, therefore, the supposition that the gammadion might have been introduced into the two countries by the same nation.

We know that the Trojans came originally from Thrace. There is, again, a very plausible tradition to the effect that the ancestors, or predecessors, of the Etruscans, and, in general, the earliest known inhabitants of northern Italy, entered the peninsula from the north or north-east, after leaving the valley of the Danube. It is, therefore, in this latter region that we must look for the first home of the gammadion. It must be remarked that when, later on, the coinage reproduces the types and symbols of the local religions, the countries nearest the Danube, such as Macedon and Thrace, are amongst those whose coins frequently exhibit the gammadion, the tétrascèle, and the triscèle. 1 Besides, it is especially at Athens that it is found on the pottery of Greece proper, and we know that Attica is supposed to have been primitively colonized by the Thracians.

In any case, to judge from the discoveries of M. Schliemann, it was especially amongst the Trojans that the gammadion played an important part from a symbolical and religious point of view; which may be attributed to the belief that it was there closer to its cradle and even nearer to its original signification. "The nations who had invaded the Balkan peninsula and colonized Thrace," writes M. Maspero, "crossed, at a very early period, the two arms of the sea which separated them from Asia, and transported there most of the names which they had already introduced into their European home. There were Dardanians in Macedon, on the borders of the Axios, as in the Troad, on the borders of the Ida, Kebrenes at the foot of the Balkans, and a town, Kebrene, near Ilium." 2 Who will be astonished that these, emigrants had taken with them, to the opposite shore of the Hellespont, the symbols as well as the rites and traditions which formed the basis of their creed in the basin of the Danube? Doubtlessly they borrowed a great deal from the creeds of the nations amongst whom they settled. But where has thegammadion been discovered amongst the vestiges of the far more ancient civilization whose religious and artistic influence they were not long before feeling?

Mr. Sayce, it is true, having met with it in Lycaonia, on the bas-relief of Ibriz, maintains the impossibility of deciding if it is a symbol imported from the Trojans amongst the Hittites, or if, on the contrary, it is to be attributed to the latter. 1 Yet, whilst the oldest "whorls" of Hissarlik go back at leastto the fourteenth or fifteenth century B.C., the bas-relief of Ibriz reveals an influence of Phrygian, and even Assyrian art, which is, perhaps, contemporaneous with King Midas, and which, in any case, cannot have risen long before the accession of the Sargonidæ; that is to say, in order to determine the age of the monument we must come down to the ninth or eighth century before our era. 2

It is therefore not difficult, here, as everywhere else, to connect the origins of the gammadion with the early centres which we have assigned to it. Even when it occurs in the north and west of Europe, with objects of the bronze period, it is generally on pottery recalling the vases with geometric decorations of Greece and Etruria, and later, on coins reproducing, more or less roughly, the monetary types of Greece. It seems to have been introduced into Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland, in the same manner as that in which the runic writing was brought from the Danube valley to the shores of the Baltic and the ocean. It may have penetrated into Gaul, and from there into England and Ireland, either through Savoy, from the time of the "palafittes," or with the pottery and jewelry imported by sea and by land from the East, or, lastly, with the Macedonian coins which represent the origin of Gallic coinage.