Hans Günther - The racial elements of European history

THE RACIAL ELEMENTS

OF EUROPEAN HISTORY

Chapter I

REMARKS ON THE TERM

'RACE,' ON THE DETERMINATION OF FIVE EUROPEAN RACES, AND ON SKULL MEASUREMENT

WE find, in general, the most

confused notions as to how the European peoples are composed of various races.

We often hear, for example, a 'white race' or a 'Caucasian race' spoken of, to

which the Europeans are said to belong. But probably, were he asked, no one

could tell us what its bodily characteristics are. It is, or should be, quite

clear that a 'race' must be embodied in a group of human beings each of whom

presents the same physical and mental picture. Physical and mental differences,

however, are very great, not only within Europe (often called the home of the

'white' or 'Caucasian' race) and within each of the countries in it, but even

within some small district in one of the latter. There is, therefore, no 'German

race,' or 'Russian race,' or 'Spanish race.' The terms 'nation' and 'race' must

be kept apart.

People may be heard speaking of a 'Germanic,' a 'Latin,' and

a 'Slav' race; but it is at once seen that in those lands where Germanic,

Romance, or Slav tongues are spoken there is the same bewildering variety in the

outward appearance of their peoples, and never any such uniformity as suggests a

race.

We see, therefore, that the human groups in question -- the

'Germans,' the 'Latins,' and the 'Slavs' -- form a linguistical, not a racial combination.

The following consideration will probably be enough to keep

racial and linguistical grouping distinct from one another. Is a North American

negro -- a man, that is, speaking American English, a Germanic tongue, as his

own -- is he a German, taking this term in its wider meaning? The usual answer

would be: No; for a German is tall, fair, and light-eyed. But now a fresh

perplexity comes in: In Scotland are found many tall, fair, light-eyed men and

women, speaking Keltic. Are there, then, Kelts who look like 'Germans'? It is

from Kelts (according to a still prevalent belief in south Germany) that the

dark, short people of Germany come. Many of the ancient Greeks and Romans are

described as like Germans. Fair, light-eyed men and women are not seldom met

with in the Caucasus. There are Italians of 'Germanic' appearance. I have taken

the anthropometrical measurements of a Spaniard with this appearance. On the

other hand, there are very many Germans, men belonging, that is, to a people

speaking a Germanic tongue, who have no Germanic appearance whatever. But are

not the people of Germany 'sprung from the old Germans'? How are these

contradictions to be reconciled? For there can be no doubt that at first sight

they are contradictions.

It is only by a careful examination of the term 'race' that a

way out is found. Anyone who is going to deal with race questions must be on his

guard against confusing Race and People (generally marked by a common language),

or Race and Nationality, or (as in the case of the Jewish people) Blood kinship

and Faith. 'Race' is a conception belonging to the comparative study of man

(Anthropology), which in the first place (as Physical Anthropology) only

inquires into the measurable and calculable details of the bodily structure, and

measures, for instance, the height, the length of the limbs, the skull and its

parts, and determines the colour of the skin (after a colour scale), and of the

hair and eyes. Martin's excellent Lehrbuch der Anthropologie (Jena, 1914)

may give the layman some idea through its size of the great number of individual

measurements and determinations that has to be made before a human body has been

anthropologically registered in all its details. Besides the inquiry into the

bodily racial structure there is the inquiry into the psychological composition

properly belonging to each race.

And what indeed is a 'Race'? The study of races and racial

questions has suffered much harm through the circumstance that many of the books

and other works that have been written about races (and so-called races), and,

above all, books that have drawn, or sought to draw, general and philosophical

conclusions from an examination into racial questions, have often said nothing

to show what they really understand by 'race.' I had, therefore, in my

Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes to go into details, which here are only

summarized.

A race shows itself in an individual human group, which in

turn only produces its like.

By an individual human group we are here to understand: a

human group marking itself off from any other human group through its own

peculiar combination of bodily and mental characteristics. Thus putting these

two statements together, we reach the following result:

A race shows itself in a human group which is marked off from every other human group through its own proper combination of bodily and mental characteristics, and in turn produces only its like.

From this we see at once that Ethnology yields hardly any

example of such a true-breeding human group -- that is, a race -- appearing

anywhere as one people, or with one form of language, of government, or of

faith. In particular, most of the peoples of Europe show a mingling of the five

European races, some, a mingling of only two or three of them; while Eastern

Europe shows an even simpler mixture. What generally distinguishes the European

peoples from one another, therefore, is, from the anthropological standpoint,

only the proportions of the mixture of the races in each case.

In all the European peoples the following five races, pure

and crossed with one another, are represented:

The Nordic race: tall, long-headed, narrow-faced, with prominent chin; narrow nose with high bridge; soft, smooth or wavy light (golden-fair) hair; deep-sunk light (blue or grey) eyes; rosy-white skin.The Mediterranean race: short, long-headed, narrow-faced, with less prominent chin; narrow nose with high bridge; soft, smooth or curly brown or black hair; deep-sunk brown eyes; brownish skin.The Dinaric race: tall, short-headed, narrow-faced, with a steep back to the head, looking as though it were cut away; very prominent nose, which stands right out, with a high bridge, and at the cartilage sinks downward at its lower part, becoming rather fleshy; curly brown or black hair; deep-sunk brown eyes; brownish skin,The Alpine race: short, short-headed, broad-faced, with chin not prominent; flat, short nose with low bridge; stiff, brown or black hair; brown eyes, standing out; yellowish-brownish skin.The East Baltic race: short, short-headed, broad-faced, with heavy, massive under jaw, chin not prominent, flat, rather broad, short nose with low bridge; stiff, light (ash-blond) hair; light (grey or whitish blue) eyes, standing out; light skin with a grey undertone.1

But how do we come to determine these five races for Europe?

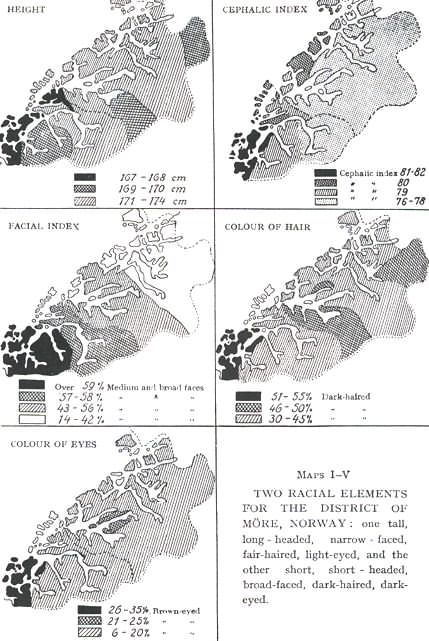

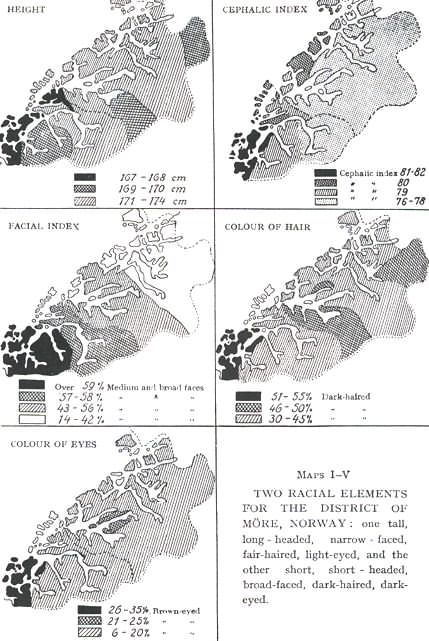

A consideration of the ethnographical map shows remarkable

correlations between the bodily characteristics there given. For instance, in

England the areas of tallest stature are at the same time those of the lightest

colouring; while in the north of France an area of lightest colouring is

likewise an area of tallest stature, and at the same time of longest heads.

Central and southern France show dark colouring and rather low stature, but the

shape of the head varies, growing longer as the Mediterranean and south-west

coasts are left; so that we are led to surmise that there are two long-headed

races represented in France: a light, tall one in the north, and a dark, low one

in the south; while in central France dark colouring, low stature, and

brachycephaly are all correlated, and thus suggest a third race. In Germany

likewise there is an area in the north-west of tall stature, light colouring,

and longish heads, with narrow faces; and in the south-east one with tall

stature also, but with dark colouring and rather short heads. In south-west

Germany dark colouring points to low stature, short heads, broad faces. These

correlations between characteristics are often so strong that when one

characteristic increases in a district others increase or decrease in more or

less the same proportion. The maps of the Norwegian district of Möre will make

this evident (see Maps I-V).

When, however, an ethnographical survey is taken too of

individual countries or parts of countries, and the recorded characteristics

(stature, shape of head and face, colour of skin, hair, and eyes) are set out in

numerical tables, so that attention is directed not towards the local

distribution of the population, but towards its grouping on the basis of its

characteristics (it being looked on as a racial mixture uniformly distributed

throughout its territory) -- when such a survey is taken, correlations among the

characteristics are again found. Thus, to take an example, in north-west and

west Germany among the taller element light colouring and long heads are found

relatively far oftener, while among the shorter element this is the case with

dark colouring, just as in the Norwegian district of Möre, and in northern and

central France. In south-west Germany, as in the whole area from the eastern

Alps as far as Greece, tall stature is the sign for dark colouring, short heads,

and also for the characteristically cut-away back of the head, and the bold,

outstanding nose. Finally, after a careful consideration of these correlated

characteristics, we reach true, unspoilt pictures of the several races making up

a given population. Even if members of the races are not to be found in all

their purity owing to a long intermingling, the correlations, by making a

definite picture of the related characteristics, would show which races have

built up the mixed population in question.

|

|

|

Fig. 1 - Dolichocephalic Skull (Index: 72.9)

|

Fig. 2 - Brachycephalic Skull (Index: 88.3)

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3 - Narrow Face (Index about 93.5)

|

Fig. 4 - Broad Face (Index about 83.5)

|

However, this mingling has not yet gone so far in Europe and

other parts of the world that we cannot find more or less clear ocular proof in

certain areas of a strong preponderance of one or the other race. North-west

Europe, especially Scandinavia, shows a certain homogeneity in its population

which strikes even the careless onlooker with its definite combination of bodily

characteristics: tall, fair, narrow-faced men and women, with long heads

standing out over the nape of the neck. The Austrian Alps show likewise, even to

a careless eye, a constantly appearing definite type described ethnographically

as the Dinaric race; among Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Albanians, and Montenegrins

it is even more striking. Spain and southern Italy show that they are settled by

a relatively homogeneous population; and the same is true of North-east Europe,

and of many small, mostly mountainous districts in Central Europe. Finally it is

from the observation of such relatively homogeneous human groups in definite

areas, when anthropology has first of all only determined the most important

physical characteristics of each race, that other features, not yet submitted to

measurement, are discovered; and the mental behaviour of such a relatively

homogeneous human group may yield suggestions as to the psychological

constitution of the race concerned.

We cannot here go into the methods of anthropological

measurement. Martin's Lehrbuch der Anthropologie (1914), and the section

on 'Technik und Methoden der physischen Anthropologie' by Mollison in the volume

Anthropologie ('Kultur der Gegenwart,' Teil iii., Abt. v., 1923), may be

mentioned here.2 The terms 'long-headed' (or 'dolichocephalic'),

'narrow-faced,' 'short-headed' (or 'brachycephalic'), 'broad-faced,' however,

need a short explanation.

A skull is dolichocephalic (long) when its length from

front to back (as it is seen from above) is considerably greater than that from

side to side; it is brachycephalic (short) when the length from side to

side is more nearly or almost equal to the length from front to back, or even

(as is sometimes found) actually equal to it.

The greatest length and breadth of the head are measured (in

a fixed way and with reference to fixed planes in the skull), and the cross

measurement is then expressed as a percentage of the measurement from front to

back; the percentage so found is called the Cranial or Cephalic Index.3

If a skull, therefore, is as broad as it is long, it

represents very decided brachycephaly with index 100. If the breadth of a skull

is 70 per cent. of the length this is said to be dolichocephalic (long) with

index 70. An index up to 74.9 is dolichocephalic (long), from 75 to 79.9 it is

mesocephalic (middling or medium), from 80 upwards it is brachycephalic (short).

The facial shape is laid down as the proportion between the

height of the face and the bizygomatic diameter, the former being reckoned as a

percentage of the latter. The height of the face is (speaking approximately) the

distance between the bridge of the nose at the level of the ends of the interior

hairs of the eyebrows and the lowest (not the foremost) point in the chin. The

bizygomatic diameter is the extreme outward distance between the zygomatic

arches (cheek-bones). The percentage number thus arrived at is called the

(morphological) facial index. Measured on the skull, a facial index up to 84.9

is broad, from 85 to 89.9 it is middling or medium, from 90 upwards it is

narrow. Measured on the living head the limits are taken lower (83.9, 84 to

87.9, 88).

A higher cephalic index, therefore, shows a shorter head, a

lower one shows a longer head; while a higher facial index shows a narrower, and

a lower one shows a broader face.

These definitions are important for the understanding of Maps

II, III, VIII, IX, and XIII.

Footnotes for Chapter I

1 In the Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes I

give other terms formerly and now used for the European races. The name Nordic

comes from Deniker, the Russian anthropologist, as does the name Dinaric (after

the Dinaric Alps, an area where this race is very prominent). The name Alpine

comes from de Lapouge, Mediterranean from Sergi, East Baltic from Nordenstreng.

Pöch, and the Austrian anthropologists who follow him, as also Kraitschek (Rassenkunde,

1923), call the East Baltic race the 'Eastern race' (Ostrasse), after

Deniker's name race orientale.

2 There are remarks, too, on methods of

measurement in the Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes. Sullivan (Essentials

of Anthropometry, New York, 1923) gives a short account of the most

important measurements.

3 Measurements made on the living head cannot be

at once compared with those made on the skull; they must first be converted.

Conversion tables will be found in the author's Rassenkunde des deutschen

Volkes.

No comments:

Post a Comment