American Pravda: Our Deadly World of Post-War Politics

Although

my main academic focus was theoretical physics, I always had a very

strong interest in history as well, especially that of the Classical

Era. Trying to extract the true pattern of events from a collection of

source material that was often fragmentary, unreliable, and

contradictory was a challenging intellectual exercise, testing my

analytical ability. I believe I even contributed meaningfully to the

field, including a short 1985 article in The Journal of Hellenic Studies that sifted the ancient sources to conclude that Alexander the Great had younger brothers whom he murdered when he came to the throne.

However,

I never had any interest in 20th century American history. For one

thing, it seemed so apparent to me that all the basic political facts

were already well known and conveniently provided in the pages of my

introductory history textbooks, thereby leaving little room for any

original research, except in the most obscure corners of the field.

Also,

the politics of ancient times was often colorful and exciting, with

Hellenistic and Roman rulers so frequently deposed by palace coups, or

falling victim to assassinations, poisonings, or other untimely deaths

of a highly suspicious nature. By contrast, American political history

was remarkably bland and boring, lacking any such extra constitutional

events to give it spice. The most dramatic political upheaval of my own

lifetime had been the forced resignation of President Richard Nixon

under threat of impeachment, and the causes of his departure from

office—some petty abuses of power and a subsequent cover-up—were so

clearly inconsequential that they fully affirmed the strength of our

American democracy and the scrupulous care with which our watchdog media

policed the misdeeds of even the most powerful.

In

hindsight I should have asked myself whether the coups and poisonings of

Roman Imperial times were accurately reported in their own day, or if

most of the toga-wearing citizens of that era might have remained

blissfully unaware of the nefarious events secretly determining the

governance of their own society.

Since

my knowledge of American history ran no deeper than my basic textbooks

and mainstream newspapers and magazines, the last decade or so has been a

journey of discovery for me, and often a shocking one. I came of age

many years after the Communist spy scares of the 1950s had faded into

dim memory, and based on what I read, I always thought the whole matter

more amusing than anything else. It seemed that about the only

significant “Red” ever caught, who may or may not have been innocent,

was some obscure individual bearing the unlikely name of “Alger Hiss,”

and as late as the 1980s, his children still fiercely proclaimed his

complete innocence in the pages of the New York Times.

Although I thought he was probably guilty, it also seemed clear that the

methods adopted by his persecutors such as Joseph McCarthy and Richard

Nixon had actually done far more damage to our country during the

unfortunate era named for the former figure.

During

the 1990s, I occasionally read reviews of new books based on the Venona

Papers—decrypted Soviet cables finally declassified—and they seemed to

suggest that the Communist spy ring had both been real and far more

extensive than I had imagined. But those events of a half-century

earlier were hardly uppermost in my mind, and anyway other historians

still fought a rear-guard battle in the newspapers, arguing that many of

the Venona texts were fraudulent. So I gave the matter little thought.

Only in the last dozen years, as my content-archiving project made me aware of the 1940s purge of some of America’s most prominent public intellectuals,

and I began considering their books and articles, did I begin to

realize the massive import of the Soviet cables. I soon read three or

four of the Venona books and was very impressed by their objective and

meticulous scholarly analysis, which convinced me of their conclusions.

And the implications were quite remarkable, actually far understated

in most of the articles that I had read.

Consider,

for example, the name Harry Dexter White, surely unknown to all but the

thinnest sliver of present-day Americans, and proven by the Venona

Papers to have been a Soviet agent. During the 1940s, his official

position was merely one of several assistant secretaries of the

Treasury, serving under Henry Morgenthau, Jr., an influential member of

Franklin Roosevelt’s cabinet. But Morgenthau was actually a

gentleman-farmer, almost entirely ignorant of finance, who had gotten

his position partly by being FDR’s neighbor, and according to numerous

sources, White actually ran the Treasury Department under his titular

authority. Thus, in 1944 it was White who negotiated with John Maynard

Keynes—Britain’s most towering economist—to lay the basis for the the

Bretton Woods Agreement, the IMF, and the rest of the West’s post-war

economic institutions.

Moreover,

by the end of the war, White had managed to extend the power of the

Treasury—and therefore his own area of control—deep into what would

normally be handled by the Department of State, especially regarding

policies pertaining to the defeated German foe. His handiwork notably

included the infamous “Morgenthau Plan,” proposing the complete

dismantling of the huge industrial base at the heart of Europe, and its

conversion into an agricultural region, automatically implying the

elimination of most of Germany’s population, whether by starvation or

exodus. And although that proposal was officially abandoned under

massive protest by the allied leadership, books by many post-war

observers such as Freda Utley have argued that it was partially

implemented in actuality, with millions of German civilians perishing

from hunger, sickness, and other consequences of extreme deprivation.

At

the time, some observers believed that White’s attempt to eradicate much

of prostrate Germany’s surviving population was vindictively motivated

by his own Jewish background. But William Henry Chamberlin,

long one of America’s most highly-regarded foreign policy journalists,

strongly suspected that the plan was a deeply cynical one, intended to

inflict such enormous misery upon those Germans living under Western

occupation that popular sentiment would automatically shift in a

strongly pro-Soviet direction, allowing Stalin to gain the upper hand in

Central Europe, and many subsequent historians have come to similar

conclusions.

Even

more remarkably, White managed to have a full set of the plates used to

print Allied occupation currency shipped to the Soviets, allowing them

to produce an unlimited quantity of paper marks recognized as valid by

Western governments, thus allowing the USSR to finance its post-war

occupation of half of Europe on the backs of the American taxpayer.

Eventually

suspicion of White’s true loyalties led to his abrupt resignation as

the first U.S. Director of the IMF in 1947, and in 1948 he was called to

testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Although he

denied all accusations, he was scheduled for additional testimony, with

the intent of eventually prosecuting him for perjury and then using the

threat of a long prison sentence to force him to reveal the other

members of his espionage network. However, almost immediately after his

initial meeting with the Committee, he supposedly suffered a couple of

sudden heart attacks and died at age 55, though apparently no direct

autopsy was performed on his corpse.

Soon

afterward other Soviet spies also began departing this world at unripe

ages within a short period of time. Two months after White’s demise,

accused Soviet spy W. Marvin Smith was found dead at age 53 in the

stairwell of the Justice building, having fallen five stories, and sixty

days after that, Laurence Duggan, another agent of very considerable

importance, lost his life at age 43 following a fall from the 16th floor

of an office building in New York City. So many other untimely deaths

of individuals of a similar background occurred during this general

period that in 1951 the staunchly right-wing Chicago Tribune ran an entire article

noting this rather suspicious pattern. But while I don’t doubt that

the plentiful anti-Communist activists of that period exchanged dark

interpretations of so many coincidental fatalities, I am not aware that

such “conspiracy theories” were ever taken seriously by the more

respectable mainstream media, and certainly no hint of this reached any

of the standard history textbooks that constituted my primary knowledge

of that period.

Sometimes

rank newcomers to a given field will notice patterns less apparent to

those long familiar with the topic, more easily discerning the forest

amid the trees. My own very superficial knowledge of 20th century

American history burdened me with fewer preconceived notions of the

pattern of those times, and the substantial body-count of accused Soviet

spies during the late 1940s gradually made me wonder about other sudden

fatalities during that same era.

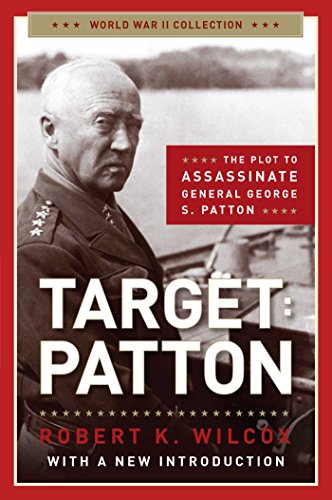

As an example, I came across Target Patton by Robert K. Wilcox, providing some very strong evidence

that the 1948 fatal car crash that claimed the life of Gen. George S.

Patton was not accidental, but was instead an assassination by America’s

own OSS, fore-runner of the CIA, which was then also heavily

infiltrated by Soviet agents. Unlike the above deaths, which were

merely highly suspicious in their timing and concentrated sequence, in

the case of Patton the evidence was considerably stronger, even

including the eventual public confession decades later of the OSS

assassin responsible, with his claims supported by the contents of his

personal diary.

At

the time of his death, Patton was America’s highest-ranking military

officer stationed on the European continent and certainly one of our

most famous war-heroes. But he had bitterly clashed with his civilian

and military superiors over American policy towards the Soviets, whom he

viewed with intense hostility. He died the day before he was scheduled

to return home to America, there planning to resign his commission and

begin a major national speaking-tour denouncing our political leadership

and demanding a military confrontation with the USSR. Prior to

stumbling across the book in question, which had been totally ignored by

the entire American media, I had never encountered a hint of anything

untoward regarding Patton’s death, nor had I been aware of the political

plans he had formulated prior to his sudden fatal accident.

Once a possible pattern has been observed, accumulating additional

pieces becomes a much more natural process. A year or so after

encountering the strongly substantiated claims of Patton’s

assassination, I happened to read Desperate Deception by Thomas

E. Mahl, a mainstream historian, whose book was released by a

specialized military affairs publishing house. This fascinating account

documented the long-hidden early 1940s campaign by British intelligence agents

to remove all domestic political obstacles to America’s entry into

World War II. A crucial aspect of that project involved the successful

attempt to manipulate the Republican Convention of 1940 into selecting

as its presidential standard-bearer an obscure individual named Wendell

Wilkie, who had never previously held political office and moreover had

been a committed lifelong Democrat. Wilkie’s great value was that he

shared Roosevelt’s support for military intervention in the ongoing

European conflict, though this was contrary to virtually the entire base

of his own newly-joined party. Ensuring that both presidential

candidates shared those similar positions prevented the race from

becoming an referendum on that issue, in which up to 80% of the American

public seems to have been on the other side.

Wilkie’s

nomination was surely one of the strangest occurrences in American

political history, and the path to his improbable nomination was paved

by quite a number of odd and suspicious events, most notably the

extremely fortuitous sudden collapse and death of the Republican

convention manager, a key Wilkie opponent, which Mahl regards as highly

suspicious.

Wilkie

went on to suffer a landslide defeat at Roosevelt’s hands in November,

but quickly reconciled with his erstwhile opponent, and was sent abroad

on a number of important political missions. Future historians would

surely have been fascinated to learn some of the internal details of how

British intelligence operatives had managed to “parachute” an obscure

lifelong Democrat into leading the top of the Republican ticket in 1940,

thereby fatefully ensuring American entry into World War II. But

unfortunately all of Wilkie’s personal knowledge of such momentous

events was forever lost to posterity when he suddenly took ill and died

of a heart attack—or according to Wikipedia 15 consecutive heart

attacks—on October 8, 1944 at the age of 52.

One

of the most powerful political figures of Roosevelt’s dozen years in

office was his close aide Harry Hopkins, who actually moved into the

White House in 1940 and remained a permanent resident for nearly the

next four years. Although Hopkins hardly bore an exalted title, being

an administrator of various New Deal programs and later serving as

Commerce Secretary, he was frequently referred to as “the Deputy

President” and certainly carried more weight than any of FDR’s vice

presidents or Cabinet members, generally being regarded as the second

most powerful political figure in the country.

Hopkins,

a former social worker and political activist, was decidedly on the

left, having his roots in a New York City progressive tradition that

shaded into socialism, while being very strongly pro-Soviet in his

foreign policy views. There are some indications in the Venona Papers

that he may even have actually been a Soviet agent, and Herbert

Romerstein and Eric Breindel took that position in their book The Venona Secrets, but John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, the leading Venona scholars, doubted this likelihood based on technical arguments.

In

the last year or so of Roosevelt’s life, his relations with Hopkins had

frayed, and when FDR died in April 1945, thereby elevating Harry S.

Truman to the presidency, Hopkins’ remaining influence disappeared.

Having spent so many years at the absolute center of American power,

Hopkins planned to publish his personal memoirs of the momentous events

he had witnessed during the years of the Great Depression and the Second

World War, but he suddenly took ill and died in early 1946, age 55,

surviving his longtime political partner FDR by only eight months.

According to the authoritative references provided in his Wikipedia entry,

the cause of death was stomach cancer. Or malnutrition related to

digestive problems. Or liver failure due to hepatitis or cirrhosis. Or

perhaps hemochromatosis. Although Hopkins had been in poor health for

many years, questions do arise when the death of America’s second most

powerful political figure is ascribed to a wide variety of somewhat

different causes.

The

particular timing of events may sometimes exert a outsize influence on

historical trajectories. Consider the figure of Henry Wallace, probably

still dimly remembered as a leading leftwing Democrat of the 1930s and

1940s. Wallace had been something of a Midwestern wonder-boy in

farming innovation and was brought into FDR’s first Cabinet in 1933 as

Secretary of Agriculture. By all accounts, Wallace was an absolutely

100% true-blue American patriot, with no hint of any nefarious activity

appearing in the Venona Papers. But as is sometimes the case with

technical experts, he seems to have been remarkably naive outside his

main field of knowledge, notably in his extreme religious mysticism and

more importantly in his politics, with many of those closest to him

being proven Soviet agents, who presumably regarded him as the ideal

front-man for their own political intrigues.

From

George Washington onward, no American president had ever run for a

third consecutive term, and when FDR suddenly decided to take this step

during 1940, partly using the ongoing war in Europe as an excuse, many

prominent figures in the Democratic Party launched a political

rebellion, including his own two-time Vice President John Nance Garner,

who had been a former Democratic Speaker of the House, and James Farley,

the powerful party leader who had originally helped elevate Roosevelt

to the presidency. FDR selected Wallace as his third-term Vice

President, perhaps as a means of gaining support from the powerful

pro-Soviet faction among the Democrats. But as a consequence, even as

FDR’s health steadily deteriorated during the four years that followed,

an individual whose most trusted advisors were agents of Stalin remained

just a heartbeat away from the American presidency.

Under

the strong pressure of Democratic Party leaders, Wallace was replaced

on the ticket at the July 1944 Democratic Convention, and Harry S.

Truman succeeded to the presidency when FDR died in April of the

following year. But if Wallace had not been replaced or if Roosevelt

had died a year earlier, the consequences for the country would surely

have been enormous. According to later statements, a Wallace Administration

would have included Laurence Duggan as Secretary of State, Harry

Dexter White at the helm of the Treasury, and presumably various other

outright Soviet agents occupying all the key nodes at the top of the

American federal government. One might jokingly speculate whether the

Rosenbergs—later executed for treason—would have been placed in charge

of our nuclear weapons development program.

As

it happens, Roosevelt lived until 1945, and instead of running the

American government, Dugan and White both died quite suddenly within a

few months of each other after they came under suspicion in 1948. But

the tendrils of Soviet control during the early 1940s ran remarkably

deep.

As a

striking example, Soviet agents became aware of the Venona decryption

project in 1944, and soon afterward a directive came down from the White

House ordering the project abandoned and the records of Soviet

espionage destroyed. The only reason that Venona survived, allowing us

to later reconstruct the fateful politics of that era, was that the

military officer in charge risked a court-martial by simply ignoring

that explicit Presidential order.

In

the wake of the Venona Papers, publicly released a quarter century ago

and today accepted by almost everyone, it seems undeniable that during

the early 1940s America’s national government came within a

hairsbreadth—or rather a heartbeat—of falling under the control of a

tight network of Soviet agents. Yet I have only very rarely seen this

simple fact emphasized in any book or article, even though this surely

helps explain the ideological roots of the “anti-Communist paranoia”

that became such a powerful political force by the early 1950s.

Obviously,

Communism had very shallow roots in American society, and any

Soviet-dominated Wallace Administration established in 1943 or 1944

probably would sooner or later have been swept from power, perhaps by

America’s first military coup. But given FDR’s fragile health, this

momentous possibility should certainly be regularly mentioned in

discussions of that era.

If

important historical matters are excluded from the media, a younger

generation of scholars may never encounter them, and even with the best

of intentions the historiography they eventually produce may contain

enormous lacunae. Consider, for example, the prize-winning volumes of

political history that Rick Perlstein has produced since 2001, tracing

the rise of American conservatism from prior to Goldwater down to the

rise of Reagan in the 1970s. The series has justly earned widespread

acclaim for its enormous attention to detail, but according to the

indexes, the combined total of nearly 2,400 pages contains merely two

glancing and totally dismissive mentions of Harry Dexter White at the

very beginning of the first volume, and no entry whatsoever for Laurence

Duggan, or even more shockingly, “Venona.” I’ve sometimes joked that

writing a history of post-war American conservatism without focusing on

such crucial factors is like writing a history of America’s involvement

in World War II without mentioning Pearl Harbor.

Sometimes

our standard history textbooks provide two seemingly unrelated stories,

which become far more important only once we discover that they are

actually parts of a single connected whole. The strange death of James

Forrestal certainly falls into this category.

During

the 1930s Forrestal had reached the pinacle of Wall Street, serving as

CEO of Dillon, Read, one of the most prestigious investment banks. With

World War II looming, Roosevelt drew him into government service in

1940, partly because his strong Republican credentials helped emphasize

the bipartisan nature of the war effort, and he soon became

Undersecretary of the Navy. Upon the death of his elderly superior in

1944, Forrestal was elevated to the Cabinet as Navy Secretary, and after

the contentious battle over the reorganization of our military

departments, he became America’s first Secretary of Defense in 1947,

holding authority over the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. Along

with Secretary of State Gen. George Marshall, Forrestal probably ranked

as the most influential member of Truman’s Cabinet. However, just a few

months after Truman’s 1948 reelection, we are told that Forrestal

became paranoid and depressed, resigned his powerful position, and weeks

later committed suicide by jumping from an 18th story window at

Bethesda Naval Hospital. Knowing almost nothing about Forrestal or his

background, I always nodded my head over this odd historical event.

Meanwhile,

an entirely different page or chapter of my history textbooks usually

carried the dramatic story of the bitter political conflict that wracked

the Truman Administration over the recognition of the State of Israel,

which had taken place the previous year. I read that George Marshall

argued such a step would be totally disastrous for American interests by

potentially alienating many hundreds of millions of Arabs and Muslims,

who held the enormous oil wealth of the Middle East, and felt so

strongly about the matter that he threatened to resign. However,

Truman, heavily influenced by the personal lobbying of his old Jewish

haberdashery business partner Eddie Jacobson, ultimately decided upon

recognition, and Marshall stayed in the government.

However,

almost a decade ago, I somehow stumbled across an interesting book by

Alan Hart, a journalist and author who had served as a longtime BBC

Middle East Correspondent, in which I discovered that these two

different stories were part of a seamless whole. By his account,

although Marshall had indeed strongly opposed recognition of Israel, it

had actually been Forrestal who spearheaded that effort in Truman’s

Cabinet and was most identified with that position, resulting in

numerous harsh attacks in the media and his later departure from the

Truman Cabinet. Hart also raised very considerable doubts about whether

Forrestal’s subsequent death had actually been suicide, citing an

obscure website for a detailed analysis of that last issue.

It

is a commonplace that the Internet has democratized the distribution of

information, allowing those who create knowledge to connect with those

who consume it without the need for a gate-keeping intermediary. I have

encountered few better examples of the unleashed potential of this new

system than “Who Killed Forrestal?”,

an exhaustive analysis by a certain David Martin, who describes himself

as an economist and political blogger. Running many tens of thousands

of words, his series of articles on the fate of America’s first

Secretary of Defense provides an exhaustive discussion of all the source

materials, including the small handful of published books describing

Forrestal’s life and strange death, supplemented by contemporaneous

newspaper articles and numerous relevant government documents obtained

by personal FOIA requests. The verdict of murder followed by a massive

governmental cover-up seems solidly established.

As

mentioned, Forrestal’s role as the Truman Administration’s principal

opponent of Israel’s creation had made him the subject of an almost

unprecedented campaign of personal media vilification in both print and

radio, spearheaded by the country’s two most powerful columnists of the

right and the left, Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, only the former

being Jewish, but both heavily connected with the ADL and extremely

pro-Zionist, with their attacks and accusations even continuing after

his resignation and death.

Once

we move past the wild exaggerations of Forrestal’s alleged

psychological problems promoted by these very hostile media pundits and

their many allies, much of Forrestal’s supposed paranoia apparently

consisted of his belief that he was being followed around Washington,

D.C., his phones may have been tapped, and his life might be in danger

at the hands of Zionist agents. And perhaps such concerns were not so

entirely unreasonable given certain contemporaneous events.

Lord

Moyne, the British Secretary for the Middle East, had been assassinated

in 1944 and UN Middle East Peace Negotiator Count Folke Bernadotte had

suffered the same fate in 1948. Declassified British documents eventually revealed

an assassination plot against Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin that same

year, and Margaret Truman’s memoirs mention a failed assassination

attempt against her own father in 1947. Zionist factions were

responsible for all of these incidents. Indeed, State Department

official Robert Lovett, a relatively minor and low-profile opponent of

Zionist interests, reported receiving numerous threatening phone calls

late at night around the same time, which greatly concerned him. Martin

also cites subsequent books by Zionist partisans who boasted of the

effective use their side had made of blackmail, apparently obtained by

wire-tapping, to ensure sufficient political support for Israel’s

creation.

Meanwhile,

behind the scenes, powerful financial forces may have been gathering to

ensure that President Truman ignored the unified recommendations of all

his diplomatic and national security advisors. Years later, both Gore Vidal and Alexander Cockburn

would separately report that it eventually became common knowledge in

DC political circles that during the desperate days of Truman’s underdog

1948 reelection campaign, he had secretly accepted a cash payment of $2

million from wealthy Zionists in exchange for recognizing Israel, a sum

perhaps comparable to $20 million or more in present-day dollars.

Republican

Thomas Dewey had been heavily favored to win the 1948 presidential

election, and after Truman’s surprising upset, Forrestal’s political

position was certainly not helped when Pearson claimed in a newspaper

column that Forrestal had secretly met with Dewey during the campaign,

making arrangements to be kept on in a Dewey Administration.

Suffering

political defeat regarding Middle East policy and facing ceaseless

media attacks, Forrestal resigned his Cabinet post under pressure.

Almost immediately afterwards, he was checked into the Bethesda Naval

Hospital for observation, supposedly suffering from severe fatigue and

exhaustion, and he remained there for seven weeks, with his access to

visitors sharply restricted. He was finally scheduled to be released on

May 22, 1949, but just hours before his brother Henry came to pick him

up, his body was found below the window of his 18th floor room, with a

knotted cord wound tightly around his neck. Based upon an official

press release, the newspapers all reported his unfortunate suicide,

suggesting that he had first tried to hang himself, but failing that

approach, had leapt out his window instead. A half page of copied Greek

verse was found in his room, and in the heydey of Freudian

psychoanalyical thinking, this was regarded as the subconscious trigger

for his sudden death impulse, being treated as almost the equivalent of

an actual suicide note. My own history textbooks simplified this

complex story to merely say “suicide,” which is what I read and never

questioned.

Martin

raises numerous very serious doubts with this official verdict. Among

other things, published interviews with Forrestal’s surviving brother

and friends reveal that none of them believed Forrestal had taken his

own life, and that they had all been prevented from seeing him until

near the very end of his entire period of confinement. Indeed, the

brother recounted that just the day before, Forrestal had been in fine

spirits, saying that upon his release, he planned to use some of his

very considerable personal wealth to buy a newspaper and begin revealing

to the American people many of the suppressed facts concerning

America’s entry into World War II, of which he had direct knowledge,

supplemented by the extremely extensive personal diary that he had kept

for many years. Upon Forrestal’s confinement, that diary, running

thousands of pages, had been seized by the government, and after his

death was apparently published only in heavily edited and expurgated

form, though it nonetheless still became a historical sensation.

The

government documents unearthed by Martin raise additional doubts about

the story presented in all the standard history books. Forrestal’s

medical files seem to lack any official autopsy report, there is visible

evidence of broken glass in his room, suggesting a violent struggle,

and most remarkably, the page of copied Greek verse—always cited as the

main indication of Forrestal’s final suicidal intent—was actually not

written in Forrestal’s own hand.

Aside

from newspaper accounts and government documents, much of Martin’s

analysis, including the extensive personal interviews of Forrestal’s

friends and relatives, is based upon a short book entitled The Death of James Forrestal,

published in 1966 by one Cornell Simpson, almost certainly a pseudonym.

Simpson states that his investigative research had been conducted just

a few years after Forrestal’s death and although his book was

originally scheduled for release his publisher grew concerned over the

extremely controversial nature of the material included and cancelled

the project. According to Simpson, years later he decided to take his

unchanged manuscript off the shelf and have it published by Western

Islands press, which turns out to have been an imprint of the John Birch

Society, the notoriously conspiratorial rightwing organization then

near the height of its national influence. For these reasons, certain

aspects of the book are of considerable interest even beyond the

contents directly relating to Forrestal.

The

first part of the book consists of a detailed presentation of the

actual evidence regarding Forrestal’s highly suspicious death, including

the numerous interviews with his friends and relatives, while the

second portion focuses on the nefarious plots of the world-wide

Communist movement, a Birch Society staple. Allegedly, Forrestal’s

staunch anti-Communism had been what targeted him for destruction by

Communist agents, and there is virtually no reference to any controversy

regarding his enormous public battle over Israel’s establishment,

although that was certainly the primary factor behind his political

downfall. Martin notes these strange inconsistencies, and even wonders

whether certain aspects of the book and its release may have been

intended to deflect attention from this Zionist dimension towards some

nefarious Communist plot.

Consider,

for example, David Niles, whose name has lapsed into total obscurity,

but who had been one of the very few senior FDR aides retained by his

successor, and according to observers, Niles eventually became one of

the most powerful figures behind the scenes of the Truman

Administration. Various accounts suggest he played a leading role in

Forrestal’s removal, and Simpson’s book supports this, suggesting that

he was Communist agent of some sort. However, although the Venona

Papers reveal that Niles had sometimes cooperated with Soviet agents in

their espionage activities, he apparently did so either for money or for

some other considerations, and was certainly not part of their own

intelligence network. Instead, both Martin and Hart provide an enormous

amount of evidence that Niles’s loyalty was overwhelmingly to Zionism,

and indeed by 1950 his espionage activities on behalf of Israel became

so extremely blatant that Gen. Omar Bradley, Chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, threatened to immediately resign unless Niles was

fired, forcing Truman’s hand.

Classics

Professor Revilo Oliver, for decades a very influential figure in far

right circles, had been a founding member of the John Birth Society and

editor of its magazine, but angrily resigned in 1966, claiming that its

leader Robert Welch, Jr. had accepted an offer of heavy financial

support in return for focusing solely upon Communist misdeeds and

scrupulously avoiding any discussion of Jewish or Zionist activities.

Based on the evidence, that accusation appears to have considerable

merit, with the JBS leadership soon treating indications of

“anti-Semitism” as grounds for immediate expulsion. Major Communist

political influence had largely disappeared in America by the late

1940s, while Jewish and pro-Israel influence grew enormously from the

early 1960s onward, and by focusing almost exclusively upon the former

and totally avoiding the latter, the JBS organization increasingly

presented a totally delusional view of American politics, which surely

contributed to its eventual decline into complete irrelevance.

Among

those who grow skeptical of establishment media verdicts, there is a

natural tendency to become overly suspicious, and see conspiracies and

cover-ups where none exist. The sudden death of a prominent political

figure may be blamed on foul-play even when the causes were entirely

natural or accidental. “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” But when a

sufficient number of such persons die within a sufficiently short period

of years, and overwhelming evidence suggests that at least some of

those deaths were not for the reasons long believed, the burden of proof

begins to shift.

Excluding

the much larger number of less notable fatalities, here is a short list

of six prominent Americans whose untimely passing during 1944-1949

surely evoked considerable relief within various organizations known for

their ruthless tactics:

- Wendell Wilkie, lifelong Democrat nominated for President by the Republicans in 1940, Died October 8, 1944, Age 52, Heart attack.

- Gen. George Patton, highest-ranking American military officer in Europe, Died December 21, 1945, Age 60, Car accident.

- Harry Hopkins, FDR’s “Deputy President,” Died January 29, 1946, Age 55, Various possible causes.

- Harry Dexter White, Soviet agent who ran the Treasury under FDR, Died August 16, 1948, Age 55, Heart attack.

- Laurence Duggan, Soviet agent, Prospective Secretary of State under Henry Wallace, Died December 20, 1948, Age 43, Fall from 16th story window.

- James Forrestal, former Secretary of Defense, Died May 22, 1949, Age 57, Fall from 18th story window.

I do

not think that any similar sort of list of comparable individuals

during that same time period could be produced for Britain, France, the

USSR, or China. In one of the James Bond films, Agent 007 states his

opinion that “Once is happenstance, twice is coincidence, three times is

enemy action.” And I think these six examples over just a few years

should be enough to raise the eyebrows of even the most cautious and

skeptical.

Foreign

leaders outraged over America’s destructive international blundering

have sometimes described our country as possessing physical might of

enormous power, but having a ruling political elite so ignorant,

gullible, and incompetent that it easily falls under the sway of

unscrupulous foreign powers. We are a nation with the body of a

dinosaur but controlled by the brain of a flea.

The

post-war era of the 1940s surely marked an important peak of America’s

military and economic power. Yet there seems considerable evidence that

during those same years, a varied mix of Soviet, British, and Zionist

assassins may have freely walked our soil, striking down those whom they

regarded as obstacles to their national interests.

Meanwhile, nearly

all Americans remained blissfully unaware of these momentous

developments, being lulled to sleep by “Our American Pravda.”

=====================

No comments:

Post a Comment