An Introspective of White Ethnocentrism

“The fiendlike skill we display in

the invention of all manner of death-dealing engines, the vindictiveness

with which we carry on our wars, and the misery and desolation that

follow in their train, are enough of themselves to distinguish the white

civilized man as the most ferocious animal on the face of the earth.”

Herman Melville, Typee, 1846

Herman Melville, Typee, 1846

Inert in the face of mass migration, and entranced by the foreign policy objectives of hostile elites, today’s “white civilized man” appear far removed from the ferocious animal perceived by Herman Melville.

While still capable of inventing all manner of war machines, and retaining the ability to engage in vindictive and devastating conflicts, we seem uniquely incapable of doing any of it in our own interests.

Instead, the “ferocious animal” of today is tame, on a leash, and obedient to obscure masters.

One of the biggest problems for the Dissident Right, and perhaps the most serious, is the seeming collapse of White ethnocentrism in the second half of the twentieth century.

The “liquid” nature of modernity, economic developments, the mass dissemination of guilt propaganda, the assault on the family, and, in some cases, the criminalization of aspects of White advocacy have all conspired to undermine, stigmatize, and destroy both national-cultural White identities (English, French, German etc.) and confluent “New World” White identities (American, Canadian, Australian etc.). These assaults from multiple angles have been so profound that by far the most prominent focus of Dissident Right activism has been to identify these external threats and then to attempt forms of rhetorical counter-attack.

As such, the broad trajectory of pro-White literature, my own included, involves material on the hostility of Jews, globalism, neocon wars, Black crime, the mechanics of White guilt, and how we are censored or otherwise exiled from the mainstream.

Discussion of these subjects is absolutely essential, even if the argument could be made that we too often neglect the great White elephant in the room — the problem that both surrounds us and confounds us: the majority of Whites who simply fail to act in their interests, and even collaborate with outsiders against their ethnic interests.

Probably no thinker in our circles has done more to move beyond neglect of ethnically pathological behaviors among Whites than Kevin MacDonald who, in a number of essays (e.g. see here, here and here) and his 2019 Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future, has almost single-handedly attempted to improve our understanding of what’s happening and to suggest possible remedies.

With the election of Donald Trump, and the evolution of European populism, White identity and political interests are also coming into increasing prominence as academic and media talking points, the work of Matthew Goodwin and Eric Kaufmann being the most obvious examples.

The methodologies of such studies involve group psychology, voting patterns, and economic analyses; their findings deserve careful study.

In the following essay, however, I propose a different way of looking at White ethnocentrism. Rather than turning a lens towards elections, the economy, group psychology, or the impacts of globalism, I want to do something quintessentially European — to turn the lens inwards.

By examining the origins and nature of my own sense of ethnocentrism, I hope to understand more about the ethnocentrism, or lack of ethnocentrism, in other Whites. I do so in the understanding that my sense of ethnic identity might be radically different from others.

In fact, I suspect that there is a multiplicity of ethnocentrisms at work among Europeans, each as unique as a fingerprint, and that this is one of the reasons for our predicament.

Nevertheless, the following essay has been written in the hope that, even given the differences of White ethnocentrisms, something valuable might be learned, or that an interesting and productive debate might be started.

*****

I honestly can’t remember a point at which I first regarded myself as

possessing a heightened, or above average, ethnocentrism. I certainly can’t recall instances before the age of 18 where I was not only conscious of being White, but proud of that fact and conceiving of myself as having interests as a White man.

Looking back on my childhood, it’s clear to me that I was raised in an overwhelmingly White environment, and ethnic outsiders, such as they existed in my world, were found almost exclusively on television or in the realm of pop music.

In other words, I was raised in an environment where being White was simply the default state, and ethnics were merely presented at the fringes of that environment as something safe, entertaining, even attractive.

One jarring exception to this state of affairs occurred in my late teens, when the 2001 Oldham Riots, and later riots in Bradford, Burnley, and Leeds, broke out in the north of England.

These riots were explicitly racial in nature, and had been prompted to a large extent by an increase in violent crime by Pakistanis and other South Asians against Whites.

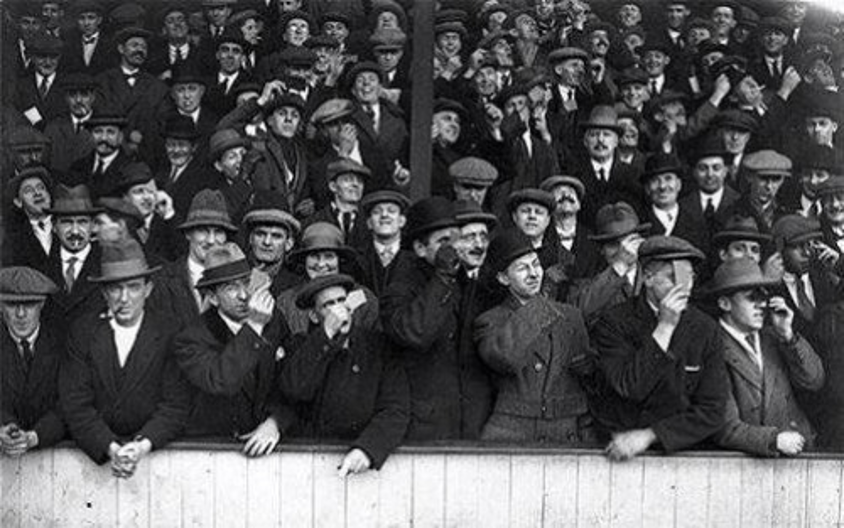

The most savage, and most publicised, of these attacks was the assault of Walter Chamberlain, a 76-year-old war veteran who was so badly beaten by three Pakistanis on his way home from a rugby match that he required surgery to rebuild his face. He had walked through “their area.”

The assault on Mr Chamberlain lit the match in the racial tinderbox, and Oldham erupted in mutual petrol bomb attacks, assaults, and arsons. It was through the blanket coverage of these race riots that I learned not only that there were growing ethnic enclaves throughout the West, but also that these brought in their wake “no-go areas,” rampant crime, and vicious anti-White hostility.

The riots in Oldham coincided with the fact I had begun to study politics at high school, part of which involved looking at race relations. In fact, just a few weeks prior to the Oldham Riots, I’d been asked to watch Mississippi Burning (1988), a crime thriller loosely based on the 1964 murder investigation concerning three civil rights workers (two Jews and a Black) by the Ku Klux Klan. Looking back on it from my current vantage point, the film is exceptional multicultural propaganda. It’s extremely well-made from a technical standpoint, boasts tremendous acting talent in the form of Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe, and is utterly relentless in demonising the population of the American South while eulogising Blacks.

Nevertheless, if memory serves me right, it had only a middling effect on my opinion of race relations, and any embryonic feelings of White guilt were swiftly destroyed one afternoon by my first encounter with the face of Mr Chamberlain, adorning the front pages of multiple newspapers as I made my way to buy lunch.

Walter Chamberlain

I followed the Oldham Riots with great interest, and recall thinking of myself as White for the first time because of the violence. Looking back over some old news articles covering those events, it’s really stunning how open some Oldham residents were about the racial realities they were forced to live with.

Take, for example, the following remark from the landlord of a local pub, the Fytton Arms: “The Asians make you racist. You’re not brought up to hate them, they make you hate them.”

Another man told reporters: “They won’t live like us. They won’t work. I don’t believe for a minute they can’t get a job because they are discriminated against. They don’t want jobs.”

On the assault on Walter Chamberlain, another added: “That’s how sick and low they are, three lads knocking 10 bells out of an old bloke. What’s he going to do back?”

In retrospect, I believe the Oldham Riots woke up a lot of White people, both near the epicenter and far from it. The riots marked the beginning of what would eventually be a remarkable rise in support for the British National Party. For those of us further afield, even if we didn’t hate Asians, to paraphrase the landlord of the Fytton Arms, “we weren’t brought up ethnocentric, but the Asians made us ethnocentric.”

Once the riots were suppressed, the government invested millions in “race relations” measures designed to bribe the Asians and gag the Whites.

The years since 2001 have witnessed endless official exhortations to “celebrate diversity” in the town, while clampdowns were announced “on anything which might be deemed offensive,” including the flying of St. George’s flag.

The town is still largely segregated, and an uneasy peace prevails.

White ethnocentrism probably remains strong in Oldham but, for now, it’s shackled and dormant.

Reflecting back on those years, after the riots my own ethnocentrism entered a short period of dormancy until, prompted by a history class that required me to watch Schindler’s List (1993) — how strange the role films have played thus far!— I was sent down another, more convoluted, path to White ethnocentrism.

*****

Until doing a short high school course of study on the rise of National Socialist Germany, part of which required coursework on Schindler’s List,

my knowledge of Jews was limited to the highly philo-Semitic teachings

of a Presbyterian Sunday school I attended between the ages of 5 and 10. It’s quite a leap to go from purportedly heroic Israelites parting seas and surviving the dens of lions to yellow stars on clothing and, in the narrative I was given, mass death on an industrial scale.

It was probably the sheer scale of this gap — the contradictory exposure to extremes of philosemitism and antisemitism — that sparked a greater than average curiosity about what exactly had happened in Europe between 1933 and 1945, and why.

Truth be told, that same curiosity is still there, and I have to say that while readers sometimes write to me saying that my essays have helped them understand certain topics, the essays are primarily a method of improving my own understanding — a kind of “thinking on paper.”

I started examining Jewish interactions with European populations, on a serious and advanced level, in my early 20s, around the same time I became a father. In terms of my own life history, these two events are connected in more senses than mere timing, since both contributed to heightened ethnocentrism.

I found Ed Dutton’s recent J. Philippe Rushton: A Life History Perspective (2018) fascinating not just because of the analysis of Rushton’s work but what Dutton had to say about Rushton’s early life, especially:

All the behaviors which Rushton has displayed—dropping out of school, marrying young, having a child young, having an affair—are predicted by low IQ. But he manifestly had a very high IQ, so, instead, these reflect a fast Life History Strategy, and specifically low Conscientiousness. Rushton was ‘living for the now’, following his impulses, with little regard for the future.Like Rushton, by my early 20s I exhibited behavior reflective of a fast Life History Strategy — I hadn’t dropped out of school but had at times been very “disruptive.”

Despite excelling academically, I was frequently in fights and spent many hours in detention, I married young (20), and had a child young (age 21 to Rushton’s 19).

I never had an affair or touched drugs (or even alcohol), but I did “live for the now,” following my impulses, with little regard for the future.

Even now, I have a higher than average number of children (4), something more typical today of lower-IQ, risk-prone populations.

And yet I also, like Rushton, continued my education alongside being a father, and graduated from university (also like Rushton) with First Class Honours, later proceeding (again like Rushton) to a PhD.

In some ways, I regard my own experience of fatherhood as slowing my Life History Strategy, something I’m sure I’m not alone in experiencing.

For me, becoming a father wasn’t just a fact of biology, but also something spiritual.

I remember holding my first child for the first time, and hearing in my mind the final words of Dante’s Paradiso: “But my will now and my desire were turned, like a wheel rotated evenly, by a love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

This dramatic shift in my personality and sense of responsibility contributed in the longer term to a slower Life History Strategy, more conscientiousness (especially regarding my children), more caution, more deliberation on risk, and greater awareness not only of my own mortality but of the threat of death more generally.

I became very protective, and began to be concerned with things like finding safe places to raise children, and safe people they could associate with.

As they grew older, I became interested in what my children were being taught, and by whom.

I began to think of myself, and my children, as part of a biological and spiritual continuum. Fatherhood had fathered a sense of ethnocentrism.

*****

This life-shift occurred around the same time I encountered troubling

incongruities in historical and contemporary representations of

Jewish-European relations. It also coincided with the fact I was travelling more with my young family, spending time not only in cities across Europe but also the United States.

There were alarming instances of ethnic crime, like the sexual assault of a family friend by a Black in Florida, an attempted break-in by Blacks in North Carolina, street harassment by gangs of Africans (twice) and Arabs (once) in Paris and Spain, attempted thefts by gypsies in Rome, but more insidiously alarming was my general sense that the White world was shrinking, becoming tragically and despondently peppered with “Oldhams.”

As my investigations of Jewish-European interactions deepened and expanded, I began to confront the Jewish role in promoting notions of tolerance and ethnic pluralism in White countries, and then encountered the work of Kevin MacDonald.

MacDonald’s own personal account of the journey to White ethnocentrism had quite a profound effect on me, since it mirrored mine (and maybe even the landlord of the Fytton Arms) in a small but important number of ways, the most important of which was that White ethnocentrism really wasn’t something we were raised with, but that environmentally impressed itself upon us.

It seemed to me that White ethnocentrism can do this either in dramatic and inescapable ways, by taking the form of a surface-level, instinctive reaction to the open and immediate violent hostility of ethnic outsiders, or it can be the result of a very broad and deep reflection on one’s immediate environment, circumstances, and group history.

The latter path would appear to require above average intelligence, as well as exposure to certain stimulating factors and an ability to assimilate a range of historical, philosophical issues.

Of course, it can also result from a combination of both — a violent ethnic confrontation that prompts deeper reflection and more intensified feelings of ethnocentrism. Actually expressing this newfound sense of ethnocentrism would then require a new set of traits altogether, including low conscientiousness (worrying less about what others would think), a greater tendency to risk-taking behaviors, and perhaps even higher than average levels of aggression.

In other words, in attempting to define an ideal type of ethnocentric White, we are back to what we might be termed the “Rushton combination” of r and K traits and strategies, with enough IQ to grasp the problem at hand, and enough recklessness to push through a wall of social stigma in order to do something about it.

This combination is, in all probability, quite rare in the population at large which would go some way towards explaining the relatively stagnant nature of White ethnocentrism at present.

In any event, it occurs to me that high levels of ethnocentrism don’t appear natural to Europeans. I think we lack the innate and instinctive forms of ethnocentrism we perceive in others, like the Jews, Arabs, and South Asians.

Even in my early exploration of Jewish matters, I think I was angered more by a sense that certain aspects of Jewish behavior (usury, nepotism, monopoly, cultural hostility) appeared, quite frankly, as “unfair” rather than being a direct attack on my interests as a White person, and those of my family or people.

Even today, some critics of my essays have mentioned that I seem to be motivated by a sense of unfairness rather than something more coldly rational, and perhaps they aren’t completely wrong.

I’m sure that, like most quintessentially European types, I haven’t entirely escaped from preoccupations with questions of fairness and morality, even if I think that to lose these traits entirely (as some Nietzscheans have advocated) would be to tragically lose something that makes us who we are.

We are preoccupied with fairness.

We are caught up with ideas of morality.

We’ve evolved that way, and it will be the challenge of our time to adapt these traits in a way that helps rather than hinders the development of ethnocentrism — something that is necessary if we are to survive as a group and remain dominant in our homelands and historically-held territories.

*****

What I find very difficult to understand and explain are those Whites

who experience utterly catastrophic inter-ethnic encounters and yet

fail to develop an ethnocentric response. Search the media and it won’t be long until you find stories of Whites who have been raped by non-Whites and find some way to blame White people for it.

Similarly, it won’t take long to find stories about fathers of murdered daughters who urge tolerance for ethnic minorities and utter non-sequiturs about what the daughter “would have wanted.”

Such stories should be compared and contrasted with John Derbyshire’s now infamous 2012 article “The Talk: Nonblack Version,” which more or less makes the case that every good White parent should educate their children about the dangers posed by non-Whites.

The reaction to Derbyshire’s piece was ferocious, but I ask a single, simple question: How many kids getting Derbyshire’s talk would go on to die at the hands of violent ethnic minorities?

I think it would rather drastically reduce the number of inter-ethnic deaths.

Every time I hear about a young White woman murdered by ethnics, either in her home country or while travelling in some remote part of the world, I think of Derbyshire’s piece and say to myself, “Well, I bet her parents aren’t ‘racists’.”

It’s really very simple — the daughters of ‘racists’ don’t think it’s a great idea to go travelling in remote India or in Muslim countries, and as such, they don’t get raped and beheaded in places like Morocco.

The standout moment of 2019’s Joker comes in the penultimate act when the punchline to Arthur Fleck’s only real joke of the film is: “You get what you fucking deserve,” and, in the cruelest of senses, this applies to those who fail to “evolve” into ethnocentrism despite the environment demanding it.

Ethnocentric Whites will manage to avoid the worst of ethnic violence, by moving away from non-Whites, by keeping their children away from them, by imparting knowledge about them, and by planning for a future in which racial realities will play an important role.

Ethnically blind Whites will continue to bear the brunt of multiculturalism.

They will be used as pawns by hostile elites, their children will be murdered, and their future will be bleak and utterly without hope.

*****

How should I characterise my sense of ethnocentrism? This is more difficult than I initially thought.

Our movement has adopted a few new labels of late, including White advocacy and even “White Wellbeing.”

There’s something about the latter that makes me cringe, despite the obvious good intent behind it.

I sometimes listen to podcasts and hear a lot about “our people” and their achievements, and things to that effect.

Again, I think this is very well-meaning, and I think we should absolutely try to encourage a sense of group pride.

But, ironically, and for me personally, despite all the demonization of the Dissident Right as a hotbed of racial supremacism and ethnic chauvinism, my sense of White ethnocentrism is quite frankly a lot more personal and humble than that.

My sense of White ethnocentrism is rooted in a desire to protect my family and to, as Bob Matthews once put it, “continue the flow” of my lineage.

In regards to how my ethnocentrism, and the ethnocentrism of other Whites, might impact ethnic minorities, it should suffice to state that the problem began with them. They’re in my homeland; I’m not in theirs.

Their presence and “racism” (which is really just White existence forced into conflict with an opposing force) are a mutual or dependent arising.

One does not exist without the other.

The presence of outsiders will provoke White ethnocentrism, at least among the healthy and adaptive.

If “anti-racist” ethnic aliens are sincere in their desire to end White racism they should take the only authentic measure guaranteed to achieve that end — they should leave, and leave quickly.

More than pride in being White, more than any sense of historical achievements by the European peoples, I simply thank whatever gods may be that I possess a sense of ethnic identity.

====================

No comments:

Post a Comment