Peyote Wisdom ================= Introduction to the Peyote Wisdom CollectionGuy Mountfrom The Peyote Book, Sweetlight Books, Cottonwood California, 1993. ©Guy MountAt this moment in American History, the practitioners of alternative herbal medicine and religion are the most persecuted and prosecuted members of society. Peyote itself is under attack from oil well development companies, dry land ranching techniques, and an ever increasing number of consumers. There is an immediate need to 1) pass laws in each state that protect the rights of all people, regardless of race or ethnic origin, to practice the peyote religion and pursue alternative healing strategies (which may employ herbs on the "controlled substances" list), and 2) protect peyote by developing nature preserves in south Texas and encouraging cultivation. The Peyote Religion and the herbal sacrament it depends on will soon be extinct unless something radical is done to establish environmental protection and decriminalize cultivation. There is also a great need to provide educational curriculum that supports a peaceful transition from an abusive "War on Drugs" to a knowledgeable use of herbal medicines. Our educational system presently teaches children that "drug use" is crazy and criminal. There is no distinction made between herbs and drugs, nor are any positive images of herbal medicines provided; so it's not surprising that American teenagers act crazy and commit crimes when they use herbs and drugs—that's what they've been taught to do! Fortunately, the Native American Church and Native American philosophy in general provide us with the lessons we need to grow as individuals, and to improve the overall health of our society. Insofar as America learned from its native people, it has provided Light to the world through democracy, religious freedom and economic reciprocity. Therefore, I hope the Peyote Religion will grow substantially in the near future to include many new practitioners from all races, and legal Peyote Churches and greenhouses in all states. Our world needs this medicine, this lifeline to the future.

====================== e 1950s a research biochemist interested in the hallucinogenic properties of the plant personally financed a graduate school program to study and determine the botanical relationships of the group and to unscramble the nomenclature. The botanical aspects are now much clearer. The peyote cactus is a flowering plant of the family Cactaceae, which is a group of fleshy, spiny plants found primarily in the dry regions of the New World. Some of the characteristics which one normally sees in cacti are not readily evident in peyote, except for the obvious one of succulence. Spines, for example, are present only in very young seedlings. However, the cactus areole—the area on the stem that usually produces flowers and spines—is well pronounced in peyote and is identified by a tuft of hairs or trichomes. Flowers arise from within the center of the plant and, like other cacti, the perianth of peyote flowers is not sharply divided into sepals and petals; instead there is a transition from small, scale-like, outer perianth parts to large, colored, petal-like, inner ones. Another characteristic which shows that peyote belongs in the cactus family is the absence of visible leaves in either juvenile or mature plants. Leaves are greatly reduced and only microscopic in size; even the seed leaves or cotyledons are almost invisible in young seedlings because they are rounded, united, and quite small. Also, the vascular system of peyote is like that of other succulent cacti in which the secondary xylem is very simple and has only helical wall thickening. BOTANICAL HISTORY

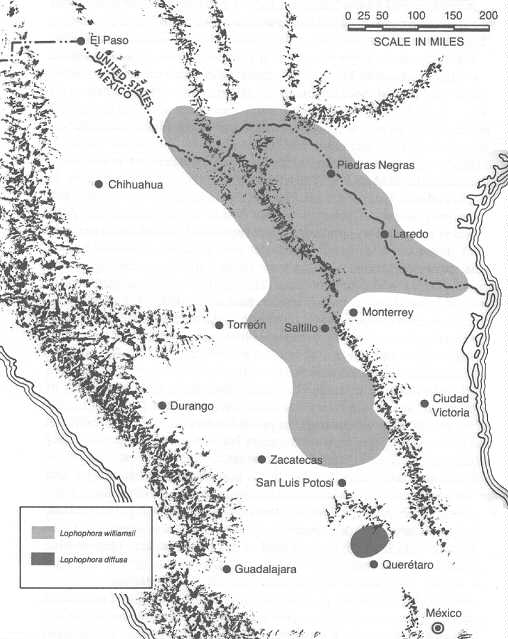

Peyote was first described by western man in 1560 but it was not until the nineteenth century that any plants reached the Old World for scientific study. Apparently the French botanist Charles Lemaire was the first person to publish a botanical name for peyote, but unfortunately the name that Lemaire used for the plant, Echinocactus williamsii, appeared in the year 1845 without description and only in a horticultural catalog. Therefore, it was necessary for Prince Salm-Dyck, another European botanist, to provide the necessary description to botanically validate Lemaire's binomial. No illustration accompanied either the Lemaire name or the description by Salm-Dyck and it was not until 1847 that the first picture of peyote appeared in Curtis' Botanical Magazine (figure 8.1).[2] In the second half of the nineteenth century the characteristics and scope of the large genus Echinocactus were disputed by several European and American botanists; gradually its limits were narrowed and new genera were proposed to contain species that had once been included in it. In 1886, Theodore Rumpler proposed that peyote be removed from Echinocactus and placed in the new segregate genusAnhalonium, thus making the binomial A. williamsii, a name which soon became widely used throughout Europe and the U.S.3 Much earlier (1839) Lemaire had proposed the name Anhalonium for another group of spineless cacti, now correctly classified as Ariocarpus.[4] Anhalonium must be considered as a later homonym for Ariocarpus, so, according to the International Rules of Botanical Nomenclature, it cannot be validly used as a generic name for any plant.[5] Ariocarpus superficially resembles peyote, but clearly is a different genus. In 1887, Dr. Louis Lewin, a German pharmacologist, received some dried peyote labeled "Muscale Button" from the U.S. firm of Parke, Davis and Company in Detroit, which had obtained the material from Dr. John R. Briggs of Dallas, Texas, earlier that year.[6] Lewin used some of this plant material in chemical studies and found numerous new alkaloids; he also boiled some of the dried "buttons" in water to restore something of their living appearance and gave them to a German botanist, Paul E. Hennings of the Royal Botanical Museum in Berlin for study. Hennings noted that Lewin's plant material appeared similar to the plant called "Anhalonium" williamsii (Echinocactus williamsii Lemaire ex Salm-Dyck) but apparently differed somewhat in the form of its vegetative body, namely in the characteristic wool-filled center of the plant. Hennings decided that the dried plant material given to him by Lewin was that of a new species, which he formally named Anhalonium lewinii, in honor of his colleague. His description was accompanied by two drawings, one of the new species, A. lewinii, and the other of the older species, A. williamsii.[7] The illustration of A. lewinii shows a high mound of wool in the center of the plant. Apparently, the drawing, which had been made from the dried plant material that Lewin had boiled in water, was an incorrect reconstruction of what had been the original appearance of the plant. When the top of a peyote dries, the soft fleshy tissue is reduced greatly in volume, whereas the wool does not decrease in size at all. Therefore, the proportion of wool to what formerly was the fleshy or vegetative part is greatly increased in the dried button. This phenomenon presumably caused Hennings and Lewin to believe that they had a new species of peyote when in actuality the plant material they had studied was that of "Anhalonium" williamsii.[8] Bruhn and Holmstedt have concluded that Lewin's plant material known as "Anhalonium" williamsii was in fact the southern species of peyote, Lophophora diffusa. The specimens which Hennings described as the new species "Anhalonium" lewinii belong to the northern species of peyote, L. williamsii.[9] Additional confusion concerning the botanical classification of peyote occurred in 1891 when the American botanist John Coulter transferred peyote to Mammillaria, a genus commonly called the pincushion or nipple cactuses Then, in 1894, a European named S. Voss confused things even more by placing peyote in Ariocarpus, the valid name for a distinct—and quite different—group of plants that had been called Anhalonium also.[11] Finally, in the same year Coulter proposed a new genus for peyote alone: Lophophora.[12] This helped clarify the nomenclatural situation because peyote had been included in at least five different genera of cacti by the end of the nineteenth century. The group of plants commonly called and used as peyote is unique within the cactus family and deserves separation as the distinct genus Lophophora. Beginning about 1900 numerous forms and variants of peyote were collected in the field and sent to cactus collectors and horticulturists in Europe and the United States. The highly variable peyote plants, not seen as part of natural populations but as individual specimens in pots, were often described as new and different species. None of the taxonomic studies, however, were based on careful field work, so little was known of the nature and range of variations within naturally occurring peyote populations. By mid-century greater accessibility of peyote locations in Texas and Mexico permitted extensive field work which has shown that plants of the genus Lophophora, especially in the north and central regions of its distribution, are highly variable with regard to vegetative characters (i.e. color, rib number, size, etc.). The number and prominence of ribs, slight variations in color, and the condition of trichomes or hairs have tended to be three of the main characters which have delineated many of the proposed species and varieties of peyote; however, these characters vary so greatly even within single populations that they are an insufficient basis for separating species—if a species is considered to be a genetically distinct, self-reproducing natural population. Field and laboratory studies show that there are two major and distinct populations of peyote which represent two species: (figure 8.2).[13] The first, Lophophora williamsii, the commonly-known peyote cactus, comprises a large northern population extending from southern Texas southward along the high plateau land of northern Mexico. This variable and extensive population reaches its southern limit in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosi where, near the junction of federal highways 57 and 80, for example, it forms large, variable clumps. The second species, L. diffusa, is a more southern population that occurs in the dry central area of the state of Queretaro, Mexico. This species differs from the better-known L. williamsii by being yellowish-green rather than blue-green in color, by lacking any type of ribs or furrows, by having poorly developed podaria (elevated humps), and by being a softer, more succulent plant. COMMON NAMES OF LOPHOPHORAThe study of peyote has frequently been confused because the plant has received so many different common names. Fr. Bernardino de Sahagun first described the plant in 1560 when he referred to the use of the root "peiotl" by the Chichimeca Indians of Mexico.[14] The two most commonly used names, "peyote" and "peyotl," are modifications of that ancient word.The actual source and meaning of the word "peiotl" is disputed and at least three theories have been proposed to explain its etymology. Several Europeans have suggested that the term "peyote" came from the Aztec word "pepeyoni" or "pepeyon," which means "to excite."[15] A derived word from this is "peyona-nic," meaning "to stimulate or activate." A similar proposal was made by V. A. Reko and extensively discussed by Richard Evans Schultes; they suggested that the term "peyote" came from the different Aztec word "pi-youtli," meaning "a small plant with narcotic action.''[16] This somewhat narrow interpretation of the kind of action should perhaps be broadened to mean "medicinal" rather than "narcotic," as the Indians certainly would have thought of the actions of the plant in the former context. Probably the most widely accepted etymological explanation for the origin of the term "peyote" was suggested by A. de Molina, who claimed that it comes from the Náhuatl word "peyutl," which means, in his words: "capullo de seda, o de gusano."[17] This, translated from Spanish, means "silk cocoon or caterpillar's cocoon." Molina's explanation, therefore, proposed that the original word was applied to the plant because of its appearance rather than its physiological action. Certainly one of the most distinctive characteristics of peyote is the numerous tufts of white wool or hair. Dried plant material has an even greater proportion of the "silky material" and most of it must be plucked prior to eating. The presence of these woolly hairs seems to be of significance because some other pubescent (hairy or woolly) plants, not even cacti, have occasionally been called peyote by Mexicans. Examples of such non-cacti are Cotyledon caespitosa of the family Crassulaceae and Cacalia cordifolia and Senecio hartwegii of the family Compositae. These plants have little in common with the peyote cactus except for their pubescence and the fact that sometimes they have been used medicinally. The Mexican word "piule," which is generally translated to mean "hallucinogenic plant," may have come indirectly from the word "peyote." R. Gordon Wasson, who has studied many hallucinogenic plants and fungi, suggested that "peyotl" or "peyutl" became "peyule," which was further corrupted into ''piule.''[18] "Piule" is also applied to Rivea corymbosa (Convolvulaceae). Other names which are apparently variations in spelling (and pronunciation) of the basic word "peyote" or "peyotl" include: "pejote," "pellote," "peote," "Peyori," "peyot," "pezote," and "piotl." The many tribes of Indians who use peyote also have words for the plant in their own languages. However, many also know and use the word "peyote" as well. Some of the tribes and their common names are: Comanche—wokowi or wohoki Cora—huatari Delaware—biisung Huichol—hícouri, híkuli, hícori, jícori, and xícori Kickapoo—pee-yot (a naturalization of the term "peyote" into their language ) Kiowa—seni Mescalero-Apache—ho Navajo—azee Omaha—makan Opata—pe jori Otomi—beyo Taos—walena Tarahumara—primarily híkuli, but also híkori, híkoli, jíkuri, jícoli, houanamé, híkuli wanamé, híkuli walúla saelíami, and joutouri Tepehuane—kamba or kamaba Wichita—nezats Winnebago—hunka Numerous other common names have been applied to Lophophora. These include: Biznaga (= carrot-like or worthless thing)—commonly applied to many globose cacti Cactus pudding Challote—used principally in Starr County, Texas, one of the major collecting sites for peyote in the United States Devil's root Diabolic root Dry whiskey Dumpling cactus Indian dope Moon, the "bad seed," "p"—these names have been applied to peyote by drug users in the United States in the late 1970s Raíz diabólica (= devil's root) Tuna de tierra (= earth cactus) Turnip cactus White mule Part of the confusion with regard to the numerous common names for Lophophora is because they are frequently applied to and/or taken from cacti of other genera or plants from another family entirely. PLANTS CONFUSED WITH OR CALLED PEYOTETwo factors have led to the confusion of various plants and the name peyote: (1) a similarity of appearance because of pubescence, a globose shape, or growth habit, and (2) a similar physiological effect or use for medicinal or religious purposes. In fact, most of the plants that are sometimes called "peyote" possess both of these characters.Many alkaloid-containing cacti are commonly called "peyote" but they are not in the genus Lophophora, and, even though some of the alkaloids are the same, probably they have few or no physiological actions similar to the true peyote. Cacti that have at one time or another been called "peyote" or the Spanish diminutive "peyotillo" are: Ariocarpus fissuratus—more frequently called "living rock" or "chautle" but also "peyote cimarr6n." A. kotschoubeyanus—usually called "Pezuna de venado" or "pata de venado." A. retusus—usually called "chautle" or "chaute." Astrophytum asterias—surprisingly similar in appearance to Lophophora. A. capricorne—also called "biznaga de estropajo." A. myriostigma—called "peyote cimarr6n," "mitra," and "birrete de obispo" (bishop's cap or miter). Aztekium ritterii—another small, globose cactus with superficial resemblance to Lophophora. Mammillaria (Dolichothele) longimamma—sometimes called "peyotillo." M. (Solisia) pectinifera Obregonia denegrii Pelecyphora aselliformis—commonly called "peyotillo" and sold as such in the native markets. Contains some of the alkaloids possessed by Lophophora, including small amounts of mescaline. Strombocactus disciformis—similar in appearance to Lophophora and occurring in the same general area as L. diffusa. Turbinicarpus pseudo pectinata Other plant families, including the Compositae, Crassulaceae, Leguminosae, and Solanaceae, also have representatives that occasionally are called "peyote." A member of the Compositae was first described as a type of peyote by the Spanish physician, Francisco Hernandez, in his early study of the plants of New Spain.[19] In his book he described two peyotes: the first, Peyotl Zacatecensi, clearly was Lophophora, whereas the other, Peyotl Xochimilcensi, apparently was Cacalia cordifolia, a Compositae which had "velvety tubers" and was used medicinally. Other sunflowers of the closely-related genus Senecio have also been called such things as "peyote del Valle de Mexico" and "peyote de Tepic." "Mescal" is the correct name for the alcoholic beverage obtained from the century plant, Agave americana, but was also used by missionaries and officials of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for peyote. Possibly this was an attempt to confuse Congressmen and the public into thinking that peyote was an "intoxicant" similar to alcohol, but it just may have been a case of incorrect information perpetuated unwittingly. The name "mescal beans" has also been applied incorrectly to peyote but actually is the common name of Sophora secundiflora of the Leguminosae. The beans of this plant contain cytisine, a toxic pyridine that causes nausea, convulsions, hallucinations, and even death if taken in too large quantities.[20] The colorful red beans have been used for centuries both in Mexico and the United States by the Indians for medicinal and ceremonial purposes, and sometimes the seeds of this desert shrub are worn as necklaces by the leaders of peyote ceremonies. The stimulatory and hallucinatory nature of these beans probably led to the confusion with peyote, especially when the latter occasionally was called "mescal." The probable relationship of the old mescal bean ceremony and the modern peyote cult also may have led to confusion by white men; this relationship is discussed in chapter 2. Peyote has also been referred to as the "sacred mushroom"; this confusion probably is the result of the similar appearance of dried peyote tops and dried mushrooms. Also, there are some mushrooms that can produce color hallucinations similar to those of peyote. The Spaniards first misidentified peyote as a mushroom late in the sixteenth century when they stated that the Aztec substance "teonanacatl" and peyote were the same; this mistake was perpetuated by the American botanist, William E. Safford.[21] He and other reputable scientists insisted that there was no such thing as the sacred mushroom "teonanacatl"; they believed that it was simply the dried form of peyote. The problem was resolved when hallucinogenic mushrooms were rediscovered in 1936 and definitely linked to early Mexican ceremonies. In recent years at least fourteen species of hallucinogenic mushrooms have been identified in the genera Psilocybe, Stropharia, Panaeolus, and Conocybe of the family Agaricaceae. It is evident that they are well known to Mexican Indians.[22] Another plant that has occasionally been confused with peyote is "ololiuhqui," which is now classified as Rivea corymbosa of the Convolvulaceae. Ololiuhqui has been widely used by Indians in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico for many purposes, such as an aphrodisiac, a cure for syphilis, an analgesic, a cure for colds, a stimulating tonic, a carminative (to relieve colic), a help for sprains and fractures, and for relief of pelvic cramps in women.[23] Recent studies have shown that the plant contains several potent chemicals which are ergot alkaloids closely related to LSD.[24] Thus, the effects are somewhat similar to those of peyote: stimulatory at first and later producing color hallucinations. Indians could easily see many "divine" actions resulting from ingestion of the seeds of Rivea and it is not difficult to understand why they and others may have confused it with peyote, another "divine" plant. Several Mexican plants and fungi are hallucinogenic like Lophophora. The following summary gives the ancient Mexican name, the botanical name or names, the plant or fungus family, and one or more of the main psychoactive substances: [25] Picietl = Nicotiana rustica L. (Solanaceae) A species of tobacco which contains nicotine. Teonanacatl = Psilocybe spp. Panaeolus campanulatus L. var. sphinctrinus (Fr.) Bresad. Stropharia cubensis Earle Conocybe spp. (All of the above are in the family Agaricaceae) The psychoactive substances are psilocybin and psilocin. Pipiltzintzinli = Salvia divinorum Epling&Javito (Labiatae) The psychoactive principle of this plant is as yet undetermined. Ololiuhqui = Rivea corymbosa (L.) Hall. fil. (Convolvulaceae) Tlitlitzen = Ipomoea violacea L. (Convolvulaceae) Both of the above members of the Convolvulaceae contain the ergot or Iysergic acid alkaloids; LSD is a synthetic derivative and is not believed to occur naturally. Marijuana is one of the best-known and most widely used substances currently classified as a hallucinogen. However, there is serious question whether it actually is a hallucination-producing plant (at least in the way that it is used by most people)—and it is of Old World origin. Marijuana is obtained from the genus Cannabis of the angiosperm family Cannabaceae.[26] It is psychoactive but has quite different effects than does peyote. MORPHOLOGYMorphological studies, including microscopic examinations, have provided much information about the evolution and relationships of the cacti. Investigations of both vegetative and reproductive parts support the proposal that Lophophora is a distinct genus consisting of two species.Vegetative parts—The growing point or apical meristem, located in the depressed center of the plant, is relatively large and similar to those found in other small cacti. The young leaf, which arises from the meristem, is difficult to distinguish from the expanding leaf base and subtending axillary bud. The leaf base, usually separated from the actual leaf by a slight constriction, grows rapidly to become the podarium, rib, or tubercle. Thus, the leaf base functions as the photosynthetic or food-producing part of peyote. With sufficient magnification the vestigial leaves of seedlings are often large enough to be identified, but they are never more than a microscopic hump in the vegetative shoot of mature peyote plants. Spines occur only on young seedlings; adult plants produce spine primordia but they rarely develop into spines. The caespitose or several-headed condition of the peyote cactus apparently occurs through the activation of adventive buds that appear on the tuberous part of the root-stem axis below the crown. Such growth often is the result of injury and almost always occurs if the top of the plant is cut off. However, some populations of peyote seem to have a greater tendency to develop the caespitose condition than do others. Epidermal cells, usually five-to six-sided and papillose (nipple-like), have cell walls only slightly thicker than those of the underlying parenchyma cells. Sometimes a hypodermal layer can be recognized early in development, but as the stem matures it does not become specialized and never differentiates from the underlying palisade tissue. Normally the epidermis is covered by both cuticle and wax; the latter substance is primarily responsible for the blue-green or glaucous coloration of L. williamsii. Stomata are abundant, especially on the younger, photosynthetically active parts of the vegetative body. They are paracytic and usually subtended by large intercellular spaces. The subsidiary cells of a stoma usually are about twice the size of neighboring epidermal cells. Trichomes are persistent for many years in the form of tufts of hairs or "wool" arising from each areole. They tend to be uniseriate on the younger areoles but are often multiseriate on older ones.[27] Ergastic substances are evident in the cortex of peyote. Usually they are druses of calcium oxalate which often exceed 250 microns in diameter, but which rarely are found within one millimeter of the epidermal layer. These anisotropic crystals can be easily seen if fresh or paraffin-embedded sections are examined in polarized light. Mucilage cells do not occur in the vegetative parts of peyote but are found in flowers and young fruits.[28] The chromosome number of peyote, like most other cacti, is 2n = 22. The root tip chromosomes are quite small, and apparently there is no variation from the basic chromosome number of the Cactaceae which is n= 11. Reproductive parts—Peyote flowers, in contrast to those of other cactus genera such as Echinocactus and most of the Thelocacti, have naked ovaries or the absence of scales on the ovary wall, a character shared with the flowers of Mammillaria, Ariocarpus, Obregonia, and Pelecyphora. Thus, in Lophophora all floral parts are borne on the perianth tube above the ovule-containing cavity. The flower color of Lophophora varies from deep reddish-pink to nearly pure white; those of L. diffusa rarely exhibit any red pigmentation, making them usually appear white or sometimes a light yellow because of the reflection of yellow pollen from the center of the flower. Development of peyote flowers is much like that of Mammillaria. Pollen of Lophophora is highly variable. Pollen of the Dicotyledonae tend to have three apertures or pores, while those of the Monocotyledonae usually have only one aperture. Peyote pollen varies greatly in aperture number, the northern population having 0-18 and the southern population 0-6. Though the grains are basically spheroidal and average about 40 microns in diameter, the varying numbers of colpae or apertures produce about twelve different geometric shapes. Such a variety from a single species or even population is rare in flowering plants. The pollen of L. diffusa has less variation than that of L. williamsii; it also has a much higher percentage of grains that are of the basic tricolpate (three-aperturate) type. Thus, the basic dicotyledon pattern is best observed in the southern population, whereas more complex grains occur in the northern localities. Small, tricolpate grains probably are more typical of the ancestors of the cacti and the more elaborate geometric designs of L. williamsii seem to represent greater evolutionary divergence and specialization.[29] Fruits of peyote are similar to those of Obregonia and Ariocarpus in that they develop for about a year and then elongate rapidly at maturity. The fruits of Lophophora andObregonia usually have only the upper half containing seeds whereas they are completely filled with seeds in Ariocarpus. The seeds of Lophophora are black, verrucose (warty), and with a large, flattened, whitish hilum. They are virtually identical to those of Ariocarpus and Obregonia although there are some minor structural differences of the testa. Lophophora seems to stand by itself in possessing a particular combination of morphological characters unlike any other group of cacti. Its nearest relatives appear to be the genera Echinocactus, Obregonia, Pelecyphora, Ariocarpus, and Thelocactus. The character of seeds, seedlings, areoles, and fruits certainly support the contention that peyote belongs in the subtribe Echinocactanae (sensu Britton and Rose) rather than in the more recently proposed "Strombocactus" line of Buxbaum. Perhaps the poorly understood genusThelocactus may be the single most closely related group.[30] BIOGEOGRAPHYThe genus Lophophora is one of the most wide-ranging of all the plants occurring in the Chihuahuan Desert; it has a latitudinal distribution of about 1,300 kilometers (800 miles), from 20 degrees, 54 minutes to 29 degrees, 47 minutes, North Latitude (figure 8.2). Within the United States L. williamsii is found in the Rio Grande region of Texas. There is a small population occurring in western Texas near Shafter; it occurs in the Big Bend region, and then it is found in the Rio Grande valley eastward from Laredo. Peyote extends from the international boundary southward into Mexico in the basin regions between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Sierra Madre Oriental to Saltillo, Coahuila; this vast expanse of Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico covers about 150,000 square kilometers (60,000 square miles). Just south of Saltillo the range of peyote narrows, is interrupted by mountains, and then expands again eastward into the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental and westward into the state of Zacatecas. It extends southward nearly to the city of San Luis Potosi where its distribution terminates (figures 8.3 and 8.4). The southern population of peyote, that of L. diffusa, is restricted to a high desert region in the state of Queretaro. This area of about 775 square kilometers (300 square miles) is isolated from the large northern populations by high, rugged mountains (figures 8.5 and 8.6).Three factors apparently are responsible for the discontinuous distribution of Lophophora between the large northern and the smaller southern population: (1) extensive saline flats in the Rio Verde region east of the city of San Luis Potosi, (2) formidable mountains: the Sierra Gorda extension of the Sierra Madre Oriental, and (3) high elevations even in the broad valleys. The relatively high desert area in Queretaro apparently is an isolated pocket of the Chihuahuan Desert. There are great elevation differences from the north to the south within the total range of peyote; the Rio Grande peyote occurs at an elevation of about 50 meters (150 feet), but in the southern portion of its range in the state of San Luis Potosi it is found at nearly 1,850 meters (6,000 feet) elevation. The elevation of the southern population in Queretaro is about 1,500 meters (5,000 feet).[31] It is unclear to what extent human beings have affected the distribution of peyote. There are areas where man has collected large quantities of the plant, such as near Laredo, Texas; near Matehuala, San Luis Potosi; and in the dry desert valley area of Queretaro. In 1961 I collected L. diffusa in a region near the road going north from Vizarron, Queretaro; in 1967 I returned to the same area but could find no peyote. Farmers living nearby told us that about a year earlier a man from a nearby village whom they called a "Padre" hired workers to collect all of the peyote that they could find in the region. The farmers didn't know why the man had wanted so many plants or what he planned to do with them, but I doubt that they were used for religious or medicinal purposes. Probably they were sold to cactus collectors—or perhaps even destroyed. Fortunately, peyote is a common and widespread plant and it occurs in many areas that are almost inaccessible. However, we may see considerable disturbance and loss of peyote populations in areas easily reached by man. ECOLOGYThe Chihuahuan Desert where peyote occurs is a type of warm-temperate desert biome. This region has considerable variation in both topography and vegetation, which has prompted ecologists to describe numerous subdivisions. Unfortunately, these subdivisions are not alike nor have they received the same names. Following the classification of the Mexican botanist, Jerzy Rzedowski, peyote occurs primarily in two subdivisions of the Chihuahuan Desert: ( 1 ) the microphyllous desert scrub, which has shrubs that are leafless or have small leaves and are represented by such plants as Larrea tridentata, Prosopis laevigata, and Flourensia cernua; and (2) the "rosettophyllous" desert scrub, with many plants bearing rosettes of leaves, such as Agave lecheguilla and Yucca spp.[32] Probably neither of these vegetation subdivisions can be considered climax communities, nor even formations, because there is continuous mixing of the two life forms. Since there is such confusion between these two subdivisions, perhaps Cornelius H. Muller's general term "Chihuahuan Desert Shrub" should be used to describe the general area in which peyote occurs.[33]The well-isolated southern population apparently is outside the region normally included within the Chihuahuan Desert. However, the presence of Larrea tridentata and other plants typical of this type of desert is an indication that it should, indeed, be included within the Chihuahuan Desert. The soils of the Chihuahuan Desert Shrub are limestone in origin and have a basic pH, from 7.9 to 8.3. These soils can also be characterized as having more than 150 ppm (parts per million) calcium, at least 6 ppm magnesium, strong carbonates, and no more than trace amounts of ammonia. The soils test negatively for iron, chlorine, sulfates, manganese, and aluminum. Phosphorus and potassium vary somewhat throughout the range, but in most localities occur in trace amounts or are not present at all. Soils from the southern locality in Queretaro are not different from those to the north.[34] As stated earlier, peyote occurs in diverse habitats of the Chihuahuan Desert, and no particular plants are associated with it in all localities. Only Larrea tridentata (creosote bush) is found in more than 75 percent of the peyote sites studied; other plants commonly found with peyote and their percentage of occurrence in the sites analyzed are: [35] Jatropha dioica (leatherplant)—70 percent Echinocereus spp. (hedgehog cactus)—70 percent Opuntia leptocaulis (pipestem cactus)—70 percent Prosopis laevigata (mesquite)—70 percent Agave lecheguilla (lechuguilla)—50 percent Echinocactus horizonthalonius (eagle claws cactus)—50 percent Mammillaria spp. (fishhook or nipple cactus)—50 percent Flourensia cernua (tarbush)—50 percent Acacia spp. ( acacia )—40 percent Condalia spp. (lotebush)—40 percent Coryphantha spp.—40 percent Neolloydia spp.—40 percent Yucca filifera (yucca)—40 percent Hamatocactus spp.—40 percent The following plants, supposedly typical of the Chihuahuan Desert, occurred in less than 40 percent of the peyote sites studied: Coldenia canescens Euphorbia antisy phylitica ( wax plant ) Koeberlinia spinosa (crucifixion thorn) Of course not all perennial plants growing with peyote have been cited, but this information indicates that peyote occurs over a broad range of vegetation types within the Chihuahuan Desert. The climatic data from the regions in which peyote grows have been analyzed to obtain an "index of aridity." Using the index of aridity devised by Consuelo Sota Mora and Ernesto Jauregui O. of the University of Mexico, [36] peyote is found to tolerate a very wide range of climatic conditions: precipitation ranges from 175.5 mm up to 556.9 mm per year, maximum temperatures vary from 29.1 degrees centigrade to 40.2 degrees, and minimum temperatures range from 1.9 to 10.2 degrees centigrade. There is also a variation in the time of year that precipitation occurs. Rains typically fall in the late spring and summer in the Chihuahuan Desert, but in certain areas some winter rains do fall. There are peyote populations in both types of areas, so probably they should be classified as being in intermediate rather than strictly summer rainfall regions. The modified index of aridity, which is based on the relationship of temperatures and precipitation, shows that Lophophora exhibits a wide range of aridity, between 64.0 and 394.0. It also appears that the index of aridity is related to elevation, although there are some definite exceptions, such as in Queretaro, where there is a relatively high elevation (about 1,500 meters or 5,000 feet) but an index of aridity that is over 115. This southern habitat, though of high elevation, may be especially arid because of the proximity of surrounding high mountains which cause a more intensified rain shadow. CHARACTERISTICS OF PEYOTE POPULATIONSPeyote consists of populations that are not only wide-ranging geographically, but which are also variable in topographical locations, appearance, and methods of reproduction. Commonly peyote is found growing under shrubs such as Prosopis laevigata (mesquite), Larrea tridentata (creosote bush), and the rosette-leafed plants such as Agave lecheguilla; at other times, however, it grows in the open with no protection or shade of any kind. In some areas, such as in the state of San Luis Potosi, peyote sometimes grows in silty mud flats that become temporary shallow fresh-water lakes during the rainy season. In west Texas peyote has even been found growing in crevices on steep limestone cliffs.The appearance of peyote also varies widely, especially in the species L. williamsii. In some cases the plants occur as single-headed individuals and in others they become caespitose, forming dense clumps up to two meters across with scores of heads. Plants in Texas do not seem to form clumps as often as those in the state of San Luis Potosi, but plants with several tops can arise as the result of injury by grazing animals or other factors. Many-headed individuals are also produced by harvesting the tops. In Texas, for example, collectors normally cut off the top of the plant, leaving the long, carrot-shaped root in the ground; the subterranean portion soon calluses and in a few months produces several new tops rather than just a single one like that which was cut off. The number of ribs present in a single head varies widely, rib number and arrangement apparently being in part a factor of age, as well as a response to the environment. Rib number within a single, genetically identical clone may vary from four or five in very young tops up to fourteen in large, mature heads (figure 8.4). At other times there are bulging podaria instead of distinct ribs. Field studies have shown that rib number and variation apparently are due to localized interactions between genotype and environment. Because of the high degree of variation occurring in a single population, rib characteristics alone are of little value in the delimitation of formal botanical taxa. Reproduction occurs mainly by sexual means. The plants flower in the early summer, and the ovules, which are fertilized during that season, mature into seeds a year later. The fruit which arises from the center of the plant late in the spring or early in the summer rapidly elongates into a pink or reddish cylindrical structure up to about one-half inch in length. Within a few weeks these fruits mature; their walls dry, become paper thin, and turn brownish. Later in the summer, usually as a result of wind, rain, or some other climatic factor, the fruit wall ruptures and the many small black seeds are released. The heavy summer rains then wash the seeds out of the sunken center of the plant and disperse them. Another method of reproduction in peyote is by vegetative or asexual means. Many plants produce "pups" or lateral shoots which arise from lateral areoles. After these new shoots have attained sufficient size they can often root and survive if broken off. If these new portions successfully grow into new plants, they are genetically identical to their parents. Surprisingly, peyote plants rarely rot if injured or cut, so excised pieces will readily form adventitious roots and can become independent plants. EVOLUTION OF PEYOTEThe evolutionary history of the cacti is not documented by fossils because their succulent vegetative parts did not lead to preservation as fossils in the dry climate. The highly specialized cactus has few distinctive characteristics that probably were present in distant ancestors, but it does appear that the tropical leafy cactus, Pereskia, may represent a form that has changed little from the non-cactus ancestral types. It and many of the more specialized cacti have many characteristics similar to the other ten families of the order Caryophyllales (Chenopodiales) in which the cacti are often placed. Most of these families, for example, have a curved embryo, the presence of perisperm rather than endosperm, either basal or free-central placentation, betalain pigments rather than the usual anthocyanins, anomalous secondary thickening of the xylem walls, and succulence.[37]The evolutionary picture from Pereskia is only hazy at best, although Pereskiopsis seems to represent an intermediate form in the Opuntia line. The "barrel" or "columnar" cacti, on the other hand, show virtually no links to one another or to any of the more "primitive" cacti such as Pereskia or Pereskiopsis. Apparently the living representatives of the cacti are terminal points of a highly branched evolutionary history, and ancestors no longer exist. Therefore, we must work with characters of living representatives to draw any conclusions regarding the past evolutionary history of the cacti, a procedure of speculation at best. Certain evolutionary trends appear evident in the two species of peyote. Pollen of L. diffusa, because of its higher percentage of the basic tricolpate type of grain, could be considered more primitive than that of L. williamsii. Likewise, James S. Todd and other chemists have shown that certain of the more elaborate alkaloids are either absent or in lesser amounts in L. diausa.38 This, they feel, indicates that L. diffusa may not have evolved and diversified to as great an extent chemically as has L. williamsii. Also, the greater variation of the vegetative body of L. williamsii, in addition to more varied habitats and a wider distribution, perhaps show a more diverse and highly evolved gene pool. Lophophora probably arose from a now-extinct ancestor that occurred in semi-desert conditions in central or southern Mexico. Morphological and chemical diversity may have then appeared in various populations as they slowly migrated northward into drier regions which were being created by the slow uplift of mountains. Perhaps L. diffusa represents one of the earlier forms that became isolated in Queretaro, whereas L. williamsii spread more extensively to the northward, producing new combinations of genes that eventually led to a distinct but highly variable species having somewhat different pollen, vegetative characters, and alkaloids from the peyote populations to the south. CULTIVATIONPeyote is easily cultivated and is free-flowering. On the other hand, one must be very patient if he wishes to grow peyote from seed, as it may take up to five years to obtain a plant that is 15 millimeters in diameter. At any stage, however, peyote can be readily grafted onto faster-growing rootstocks, and this usually triples or quadruples the plant's rate of growth. Japanese nurserymen, for example, have obtained peyote plants large enough to flower within a period of 12-18 months by grafting the young seedlings onto more robust root stocks.To insure the obtaining of fertile seed, it is advisable to out-cross peyote plants by transferring with forceps some stamens containing pollen from the flower of one plant to the stigma of the flower of another. Propagation can also be accomplished by removing small lateral tops from caespitose individuals. The cut button or top should be allowed to callus for a week or two and then planted in moist sand or a mixture of sand and vermiculite. It is wise to dip the freshly cut portion in sulfur to facilitate healing. Rooting is best done in late spring or early summer. Eventually a new root system will develop from the top; the old root will produce several new heads to make a caespitose individual. Soil conditions for the cultivation of peyote are not too critical. As the natural soil for peyote is of limestone having a basic pH, one should provide adequate calcium, insure that the soil is slightly basic, and provide good drainage. Peyote should be watered frequently (every four to seven days) in the summer but very little or none at all in the winter. Fertilizer should be applied while the plants are being watered during the growing season, especially May through July. Peyote hosts few insect pests and does not need to be treated differently from other cultivated cacti and succulents with regard to pesticides. Greenhouse-grown peyote plants sometimes develop a corky condition; this brownish layer often covers most of the plant and is not natural. Its cause is not known. The propagation of seeds is a rewarding experience but requires great patience. Seeds should be sowed on fine washed sand and then covered with one to two millimeters (about one-eighth inch) of very fine sand. Cover the flat or pot with a plastic bag or plate of glass and place an incandescent light (60 watt) or Grolux lamp about twelve inches above the sand. These provide both heat and light. The sand should be kept moist to insure that the humidity is high and that the young plants will not dry out as they first sprout. Germination usually occurs within two or three weeks but growth of the seedlings is exceedingly slow. The plants should be transplanted and thinned after they are about one centimeter (one-fourth of an inch) in diameter. Most states, as well as the federal government, now prohibit the possession of peyote (see chapter 9), and apparently one is in violation of the law even if peyote is grown as part of a horticultural collection. NOTES TO CHAPTER 81. Jan G. Bruhn and Bo Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research: An Interdisciplinary Study," pp.384-85.2. William Jackson Hooker, "Tab. 4296. Echinocactus Williamsii." 3. Theodor Rumpler, Carl Friedrich Forster's Handbuch der Cacteen kunde, p. 233. 4. Charles Lemaire, Cactearum Genera Nova et Species Nova en Horto Monville, pp. 1-3. 5. J. Lanjouw and others (eds.), International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, p. 50. 6. Bruhn and Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research," pp. 358-60. 7. Paul Hennings, "Eine giftige Kaktee, Anhalonium lewinii n. sp.," p.411. 8. Edward F. Anderson, "The Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 305-06. 9. Bruhn and Holmstedt, "Early Peyote Research," pp. 384-85. 10. John M. Coulter, "Manual of the Phanerogams and Pteridophytes of Western Texas," p. 129. 11. A. Voss, "Genus 427. Ariocarpus Scheidw. Aloecactus," p. 368. 12. John M. Coulter, "Preliminary Revision of the North American Species of Cactus, Anhalonium, and Lophophora," pp. 131-32. 13. Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," pp. 299-303. 14. Fr. Bernardino de Sahagun, Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana, X, p. 118. 15. Richard Evans Schultes, "Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and Plants Confused with It," pp.61-88. 16. Ibid. 17. A. de Molina, Vocabulario de la Lengua Mexicana, p. 80. 18. R. Gordon Wasson, "Notes on the Present Status of Ololiuhqui and the Other Hallucinogens of Mexico," pp. 166-67. 19. Francisco Hernandez, De Historia Plantarum Novae Hispaniae, pp. 70-71. 20. Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann, The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, p. 99. 21. William E. Safford, "An Aztec Narcotic," p. 311. 22. Schultes and Hofmann, Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, pp. 36-39. 23. Hernandez as reported in Schultes, "Peyote and Plants Confused with It," p.74. 24. Schultes and Hofmann, Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens, pp. 144-51. 25. Wasson, "Notes on Ololiuhqui," pp. 164-75. 26. Richard Evans Schultes, William M. Klein, Timothy Plowman, and Tom E. Lockwood, "Cannabis: An Example of Taxonomic Neglect," pp.360-62. 27. Norman H. Boke and Edward F. Anderson, "Structure, Development, and Taxonomy in the Genus Lophophora," p. 573. 28. Ibid., pp.573-74. 29. Edward F. Anderson and Margaret S. Stone, "A Pollen Analysis of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 77-82. 30. Boke and Anderson, "Structure, Development, and Taxonomy," p. 577. 31.Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," pp. 301-02. 32. Jerzy Rzedowski, "Vegetacion del Estado de San Luis Potosi," pp. 219-20. 33. Cornelius H. Muller, "Vegetation and Climate of Coahuila Mexico," p. 38. 34. Anderson, "Biogeography, Ecology, and Taxonomy," p. 302. 35. Ibid., pp. 302-03. 36. Consuelo Soto Mora and Ernesto Jaurequi O., Isotermas Extremas e Indice de Aridez en la Republica Mexicana, pp. 26-28. 37. Arthur Cronquist, The Evolution and Classification of Flowering Plants, pp. 177—80. 38. James S. Todd, "Thin-layer Chromatography Analysis of Mexican Populations of Lophophora (Cactaceae)," pp. 395-98.

Figure 8.2

|

| —David L. Walkington Department of Bacteriology University of Arizona |

==========================

Through The Lens Of Perception

Hal Zena Bennett

Shaman's Drum, A Journal Of Experiential Shamanism: Fall, 1987

now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known."

—I Corinthians

Nearly thirty years ago, I spent a summer in Mexico, much of it in a small village two hours by bus up the coast from Acapulco. As far as I know, the village had no name but was referred to as "the turnaround" (in Spanish, of course) because it was here that the third-class bus turned around and headed back over the mountain to Acapulco. I had gone there on the recommendation of a friend to escape the modern hotels and the tourist crowd. But I was not entirely prepared for the primitive conditions I met, or for a certain adventure that came to me. Instead of a modern hotel room, I found myself sleeping on a cot, covered only by a light sheet, just one of seven other rugged souls who had chosen this thatched roof dormitory over the more elegant accommodations available two hours south.

We always arose at sunrise, helped fold the cots, then stashed them away in one corner of the room. That done, we sat around and sipped coffee from crude, terra-cotta cups as we waited for breakfast to be served by the proprietor and his wife. Eating and sleeping under these conditions, created a bond between strangers, in spite of the language barriers. I knew enough Spanish to ask for basic life essentials, and the others, mostly Mexican students from the City, knew enough English to make small-talk.

One afternoon I met a man on the beach who said he was a tourist guide. He offered to take me up to the top of the mountain—I do not think I ever heard the name of it—where he promised to show me the most spectacular view imaginable. The fee for this jaunt was reasonable, and having nothing better to do I agreed to go with him.

The man's name was "Sen", and he was a wiry but strong looking little man who appeared to be in his early sixties. He wore only faded khaki pants and a red T-shirt with a flying hawk emblazoned across the chest. Underneath the bird, written in Spanish, was the name of a local beer. Sen was dark-skinned and had long black hair that reached nearly to his shoulders. His face had sharp Indian features, and when he smiled he revealed two front teeth capped in gold. Just after noon, Sen packed a small knapsack with staples that he purchased from a groceria a short ways from our camp. Then we set out on foot in the most casual way imaginable. He pointed to the mountain peak where we were going. It looked to me to be miles and miles away. He assured me, however, that it was a much shorter distance than it looked, and I was not to worry.

We traveled on foot for most of the afternoon, taking what he called "El Sombre"—the shaded trail on the eastern slopes of the mountain, which protected us from the torturous rays of the afternoon sun. The trail was difficult, very steep at times, and not well maintained. I failed to keep track of the time, but we must have traveled for at least four hours before we stopped.

Finally Sen announced that we had arrived at our destination, and he led me to the mouth of a large cave, where we sat down to rest. I would guess that the cave was approximately two thousand feet above the sea. Less than a mile to the west, and seemingly straight down, was the ocean.

As Sen had promised me, it was a most spectacular view. The steep walls of the mountain amplified the sounds of the waves far below, giving the illusion that the sea might have been only a stone's throw away. From this aerial view, somewhat magnified by a peculiar atmospheric distortion, one could watch the waves rolling gently in upon the beautiful white beach, appearing as they might through binoculars.

I was aware of Sen squatting down on the ledge a few feet off to my left and a foot or two behind me. I turned and watched as he took a small package from his day-pack. He had something wrapped up in newspapers, which he set down in front of him.

He carefully unfolded the papers, smoothing the edges out over the ground. At the center of the square of newspaper were six objects that looked like green cactus apples with flattened tops. Each one had a feathery white tuft growing out of its top.

With a small, razor-sharp, stag handled jackknife, Sen removed the tufts and sliced the cactus apples pie-like into narrow wedges. "What is it?" I asked, in Spanish.

"It is medicine for fixing your eyes," Sen said. He looked up and grinned mischievously, making a peculiar fanning gesture with his hands around the area of his eyes.

"Peyote," I said. He nodded, inviting me to share the peyote with him.

I would have been reluctant except that back in the States, I had taken peyote three times. Each time had been under controlled conditions, and in the name of medical research. We had taken our peyote as a dried powder inside gelatin capsules. I had only seen pictures of it in its raw form.

I had experienced a pleasant, mildly altered state of consciousness in these experiments. So, naturally, I had no particular anxiety about taking the peyote with my guide.

Sen showed me how to eat the narrow slices from the buttons. He tipped back his head, opened his mouth wide, and placed a single slice far back on his tongue. Then he rocked his head forward and swallowed. On my first try, I failed to get the peyote far enough back on my tongue, and the foul, earthy taste made me wretch.

Sen repeated his instructions, and this time I got it right. Together we consumed five ripe buttons in about a half an hour. Then we sat quietly, breathing slowly and deeply in a way that Sen said he had been taught to do. I recall feeling nauseous at first, but had no trouble with it when I followed Sen's breathing instructions.

It was late evening. The sun was setting, and the sky had turned a deep scarlet. At the horizon, sea and sky blended as one in a symphony of reds and yellows.

Spread out between the ocean and the cave where we sat, I saw a strip of tropical jungle. Here was a world of lush greens, ferns and palms in varying tone, now wearing an aura of pink created by the fading sun.

Blowing in from the ocean, the evening air was cool, heavy with the earthy fragrance of the jungle, of naturally composting vegetation and moist soil, and of flowers which I could not see.

"It is like I told you it would be," Sen said. "Do you agree?"

I nodded, agreeing that indeed it was very beautiful.

Minutes passed; then Sen announced, "Darkness will be coming soon."

It took a moment for these words to sink in. And then the horror of it struck me. We had just spent the entire afternoon hiking up an extremely precipitous trail, along which we encountered many hazards. Several times I had clung to the rock face of the mountain to traverse a section of the trail washed out by storms, risking a fall of several hundred feet. Another time a large snake blocked the trail. Sen chased it off with a stick, all the while assuring me that the snake was not poisonous, though its bite could be harmful.

The realization that I might have to go down this same trail in the darkness startled me. How could I have been so stupid! Why had it not occurred to me, until now, that it would be dark when we returned!

I was furious with Sen. What sort of person would guide me to such a place, heedless of the threat to my well-being. Surely he realized it would be dark before we returned.

I then became aware of a deep, groaning roar coming from deep within the cave behind me, and I leapt to my feet with visions of being attacked at any moment by a wild animal whose peace we had disturbed. I began swearing and jumping around, unable to decide which way to turn. I knew there was a washout less than a hundred yards down the trail, and it was already too dark to safely cross it.

Sen continued to sit at the mouth of the cave, completely unperturbed. In fact, he was wearing a toothy grin that did nothing for my sense of security.

Again I heard the groaning roar within the cave. "What the hell is that?" I cried. "Don't you think we should get out of here?"

"Is it such a bad sound?" Sen asked. "I find it rather pleasant."

"Pleasant!" I said, still searching for an escape. "How can you sit there so calmly? Do you know what it is?"

"It is a sound."

"Of what?"

Sen shrugged. "Who knows?"

At that moment, I sensed that he knew something which I didn't. He'd been here before. Or at least he claimed that he had been. He obviously knew that the sound wasn't a threat to our safety. Or did he? I knew nothing about the man, other than what I saw. He had told me nothing about himself. Where had he come from? For all I knew he cold be a complete fool, or a madman—some sort of murderer who lured people out into the wilds where he slaughtered them. After all, who would ever find me out here? Who even knew—or for that matter cared—where I'd gone?

"Sit down," he said sternly, pointing to the empty boulder at the mouth of the cave where moments before I had been sitting.

"Not on your life," I said.

He looked at me incredulously. "No? Then, where are you going to go?"

"I'm leaving," I said. "I'll go back down the trail."

"Surely you're joking."

"I'm not joking at all," I said. "I've had plenty of trail experience back in California.

"Suit yourself," he said. "But you'll miss the best part of the sunset. Look." He pointed over the horizon.

Against my better judgment I turned to find out what he thought could possibly be so important. At the edge of the horizon the sky was ablaze with a bright pattern of red and yellow light, twisting slowly into a shape that resembled a spiral galaxy. My breath was literally taken away by the beauty of it, and for a moment I completely forgot my plight. "My god, what is it?" I asked.

"It is what I promised you," Sen said. "I have kept my word."

In spite of myself I sat down and stared out over the horizon. For an hour or more I watched as the spiraling colors played at the end of the ocean. The galaxy of colors was huge, awesome in its proportions, and seemed to have a life of its own, twisting and turning almost playfully, as though it had an intelligence and was performing a dance with the Earth. Then suddenly it was gone, and we were plunged into darkness.

The groaning roar rose from the cave behind us, and this time I was able to study it, to listen with a calmer mind. Rather than like an animal, it sounded this time like two gigantic boulders being ground slowly together, emitting a voice from somewhere deep down in the earth beneath our feet. I had visions of two continental plates scraping against one another, their sound amplified and made more resonant by a long tunnel in the cave.

"Listen," Sen said. "Listen."

I did, and the sound varied, not like a voice so much as like music made by a gigantic instrument whose shape and mechanics I could barely imagine.

"Didn't I tell you?" Sen said excitedly. "Didn't I tell you I would show you a wonderful place?"

He leaned down and picked up his knapsack. Reaching inside, he produced a round object which he handed to me. It was too dark to see what it was, but from the size and texture I guessed it was an orange.

"Supper," Sen said, announcing this in a completely matter-of-fact tone.

Was he kidding? Was this really his idea of an adequate supper after our arduous climb to this place? Without comment, I sullenly peeled and sectioned the orange, determining that I would eat it slowly, savoring every bite.

I was aware of Sen rolling his orange between his palms, the peeling still in place. He was doing this in a very studied, very methodical way, and I grew curious. As I watched him, I also became aware that the mountain was growing brighter and brighter, almost as though a huge spotlight was being pointed at us. I looked up and saw the edge of a full moon just emerging from behind the top of the mountain, another five hundred feet above us. This was providing us with enough light to safely make our way down the path, if that is what we chose to do.

I looked at Sen, meaning to suggest this to him. But now he was ripping into the orange like a starving ape, tearing off great chunks and burying his face in his hands as he sucked and chewed at the fruit. I was disgusted by his behavior, and wondered if he always ate like this. He finished, reached into his knapsack for a bandanna, and wiped off his face and hands, licking his fingers now and then to get rid of the sticky juice. This done, he lay down, arranged the knapsack under his head, and appeared for all the world to be getting ready to take a nap.

"Shouldn't we be getting back while we still have some light from the moon?" I asked.

"What's the hurry? Have you got an appointment with the doctor or something?" To this he chuckled stupidly, like a man unaware of the fact that no one else thought his joke funny.

"When are we going back?"

"Why don't you just enjoy yourself," he said. "Take it easy."

I don't know whether I was more angry than anxious, but I could see that there was no sense in trying to budge him. He had his own plans for us, and he was obviously not going to let me in on them. I was completely at his mercy.

I leaned back and started picking at the orange that I had sectioned so carefully. I picked up the first section and was about to put it in my mouth when I felt something moving across my hand. I looked down at the orange section. A tiny lizard, about the length of my little finger, clung to the fruit. I grabbed it by the tail and flung it out into space, disgusted by the thought that had I not felt it moving in time, I would have bitten into H. and might at this very moment be spitting out its bleeding carcass.

I was careful after that, brushing off each section of fruit and inspecting it in the moonlight before popping it into my mouth. By the time I had finished eating, Sen was sound asleep. His rasping snores indicated to me that it would be no use trying to awaken him, at least not for an hour or more.

I felt restless and uneasy. From far below us I could hear waves lapping against the beach, and this was soothing. Then, every few minutes, the cave made that peculiar groaning sound, a sound to which I had now become accustomed. To pass the time, I decided that I would try to plot how long were the silences between the cave's groans, but after an hour or more I could determine no apparent pattern, and eventually gave it up.

The moonlight slowly faded, and again I became anxious as darkness closed in around me. Now, every sound seemed amplified, and I became aware of live things all around me. High-pitched whistles from inside the cave suggested the presence of bats. Rustling in the trees suggested night birds, or perhaps nocturnal animals. None of these things particularly disturbed me, though they didn't exactly put me at ease, either. I had spent many nights under the stars back in the States, hiking in the Sierras. But I have to admit that these sounds were not familiar to me, and my inability to identify them put my nerves on edge.

The sky was brilliant with stars, the Milky Way like a great sea of light. Several times I saw meteorites trailing across the sky. In spite of my nervousness, I caught myself dozing, jerking to attention when by body relaxed, and I almost lost the balance of my sitting position. At last I gave into H and lay down, staring up at the sky until I fell asleep.

The next thing I knew there was a shriek, and I sat bolt upright, not knowing what to expect. The shriek shattered the stillness once more and I looked up, having determined that the sound had come from above and to my left. As I searched the darkness, the shriek came again and a huge bird, with a wingspan of at least six feet, swooped down, coming right for me. I leapt behind Sen's rock—where he continued to sleep soundly—just as the great bird shot by.

As the bird passed, less than a foot from my face, I saw its talons extended as though for a kill. But that was not the worst of it. Just a few feet past me, it stopped in mid-flight, seemed to gather itself into a ball, and suddenly changed directions, facing me once again as thought preparing for another attack. I shielded my face with both arms, fully expecting to feel its sharp talons dig into me at any moment. But then it stopped. Facing me directly, flapping its wings gently, hanging in the air like a feathery helicopter, I thought I heard it make a sound.

Surely I was dreaming. But I knew I wasn't. I looked directly at the bird and saw that it had a human face. I rubbed my eyes, certain that what I was seeing couldn't possibly be true. But it was. The bird had a human face. Moreover, it was a face I recognized. It was Sen's face! Sen had taken the form of a giant night-hunter. I glanced down on the ground where he had been sleeping. Indeed, he was gone. And there, as clear as the paper on which these words are printed, was the bird—Sen in the form of a bird, hovering before my eyes, flapping his wings gently, evenly, as he held his space in the air.

"What are you doing?" I asked, at the moment not thinking how indescribably unbelievable it was to be talking to a bird who had taken the face of my companion.

"Coo! Coo! Coo!" the bird said. This was followed by laughter—laughter that I knew was Sen's. The laughter ended and was followed by his stupid chuckling. Did he somehow expect me to share in his little joke? I didn't think it was funny. In fact, I was shaking like a leaf, still unable to give a rational explanation for what I'd seen. Besides, the bird was still there, still hovering within an arm's length me.

I decided to treat it as an everyday occurrence. After all, maybe it was a dream. I had heard that the best way to stop a person or situation that you don't like in a dream was to rein in your rational self and tell it to go away. I did this, and heard the bird reply, "Go away to where? You said yourself, it wasn't safe to go down the trail in the dark."

"But you're a bird," I said. "You can fly."

"Oh, right. That's right," I heard Sen say. "Goo'bye, then."

And with this, he disappeared. By the light of the stars I watched him gather his wings under him and plunge off the cliff where I was sitting. I watched as he circled gracefully, changed direction, and disappeared, skimming the treetops in the jungle below, apparently continuing his night hunt.

Then, startled, I suddenly realized that I was all alone at the mouth of the cave. Could this have actually happened? Had Sen been transformed, somehow, into the body of a bird, a giant owl or whatever it was? In any case, it was very clear to me now that I was left alone on the mountainside.

I heard the crunch of gravel on the path a hundred feet away, off to my right. I called out, "Sen, is that you?"

Much to my relief, my companion came into view, hooking up his pants.

"Where were you?" I asked.

"I went to take a crap," he said. "What's wrong? Are you late for your appointment again?" This was followed by his usual stupid chuckle. Then he went back over to his rock and stretched out, arranging the knapsack under his head as before.

"I've had enough of this," I said. "Stop fooling around with my head."

"I'm going back to sleep," he said. "Wake me when the movie's over."

I could not believe his audacity or his incredible coolness. Within seconds he was sound asleep again, apparently oblivious to everything going on around him. I lay brooding, angry, thoroughly shaken by everything I had been through that night. I wanted to grab Sen by the shoulders and shake him awake. I wanted to scream at him, to tell him how much I resented the games he was playing with me. I didn't know how he was accomplishing what he was doing, and I didn't care. I just wanted it to stop.

I huddled close to my rock like an animal guarding its territory. I myself began to feel like an animal, destined to live out its life in the wild. I felt a warming sensation throughout my body, a rippling of muscle. Perhaps it was due to a warm breeze emitted from the mouth of the cave. It was certainly possible that there were hot springs somewhere below that occasionally emitted heat which escaped to the outer vestibules.

I found myself staring steadily and angrily at the sleeping Sen. I had never felt such hatred for another man. But as I stared at him I could not identify my anger. I felt a strange fear, like nothing I'd ever felt before. It was as though this man was an intruder in my life, that he was threatening me or something that belonged to me.

I watched him cautiously, waiting for him to make the slightest move in my direction, a move that would indicate that I would have to fight with him—perhaps until one or the other of us was dead. I determined that I would be the victor. After all, I was larger, more powerful than he.

Sen's snoring stopped. He took a deep breath, then suddenly began to tremble all over as though he was having some sort of fit. The light changed and I saw a giant cat, a mountain lion or a panther standing between me and him, teeth bared.

"Sen," I cried, wanting to warn him. But a strange sound came from my throat, a hissing that I could barely identify with.

Sen sat bolt upright and looked calmly past the cat. In fact, his gaze was piercing, looking right through the cat into my eyes. "Stop this nonsense right now," he said. "You need your sleep. You'll be exhausted in the morning."

"The cat," I said. "Don't you see it?" At that moment I wasn't certain of anything. I could not clearly see the cat myself. It was too close for me to see. I was terribly confused. Why couldn't he see it? I was aware only of its threatening posture, baring its teeth, ready to pounce.

"Of course I see it," Sen said. "It's your cat. It's not going to hurt me."

My cat, I thought to myself. Mine? And then I asked, "What makes you so sure?"

"I am just sure. I am just sure." He waved his hand in front of my face. Suddenly I was calm. I felt spellbound. "You see?" Sen said.

Sen lay back down, and in seconds he was sound asleep again. I drew back away from him, toward the mouth of the cave. The cat came back into focus for me. It was just me and the cat now. The cat turned, gazed into my face, and appeared to grin.

Was all this truly my own creation? I stared back at the cat. Its face lit up, glowing, as though it had been a plastic mask; now someone had turned on a light behind the cat mask, exposing the illusion. The body of the cat vanished and I was looking just at its face, at that backlit mask. Then the mask of the cat began to dissolve, as though the heat of the light behind it was causing it to melt. Soon it was nothing more than a molten blob turning in space like a star. As I watched, it began to reshape itself into a much more geometric form.

After a few moments its transformation was complete. Round, saucer-shaped, it turned slowly in the space before my eyes. The light still shown within it, as though it possessed its own source of illumination. It turned again and again, revealing its full configuration, thin and elliptical from the side, round and perfectly symmetrical from the front. It was a lens, like the lens from a telescope or a magnifying glass. But this lens had an organic appearance—not unlike a living cell, translucent and soft, definitely alive—a geometric jellyfish.

I moved closer to the lens. Deep inside it I saw movement. What were these shapes? I saw many images from my childhood—my brothers, the house where I'd lived during my high school years in Michigan, my parents, my first lover. I thought about how people often reported seeing their lives flash before their eyes when they were faced with death. Could this be the case? Was I near death? I looked deeper into the lens, as though I might find the answer there. I saw a cat, a powerful mountain lion. There was also a giant bird. There was a groaning cave, and a beautiful sunset over the ocean. There was a rugged trail up a mountain, and a man. I looked more closely. It was Sen. He was sleeping by the rock, his head on his knapsack. I could not figure out where he was—in the lens, or beyond it, or both?

The lens turned in the air. I closed my eyes, trying to block it out, trying to see around it, or to see a clear place through it where the world beyond would not be distorted by the images inside the lens. But I could not escape the lens' influence, and now I was aware that it was turning deep in my consciousness, in the same space out of which dream and imagination are created. I had never before noticed how large this mental space I called imagination could be. It had no limits, no beginning or middle or end. It seemed to stretch out in all directions, a vast landscape whose borders were as unlimited as space itself.

At one moment I could be on the mountainside with Sen, in Mexico. A second later I was back in Michigan, many years before, a boy of twelve riding his bicycle on a rain-slick asphalt street. A second after that I was driving across the Arizona desert in January, with a carload of friends, all in our early twenties, heading back to California after a Christmas holiday with our families in Michigan. Now I shifted to a backpacking trip in the high Sierras, where I fished for trout on the bank of a mountain lake.

Where was the lens now? I couldn't find it. It seemed to have merged with all the rest, lost in the jumble of everything I held in my consciousness. I felt panic. Losing the image of the lens was like losing a treasure I had dreamed of discovering all my life. Then there was a long moment of perfect clarity when I realized what had happened to the lens. I saw that it hadn't disappeared at all; the lens was my consciousness, not simply a piece of it.

For a long time I just sat quietly and thought about this. It seemed to me that the lens was like a vehicle for my awareness, giving me an identity separate from the rest of the world. This was the image I had been seeking since I was a child. A thousand questions and speculations that I had entertained along the way now focused on this lens image.

Having the sense of separateness which the lens provided seemed to me both exciting and frightening. It meant that I was not like an ant, with instincts—that is, pre-programmed responses built in—dictating my every action. It meant that I was capable of creating my own program, or even of overriding whatever biological or God-given programs might be built in.

My decisions, my fears, my dreams, my acquired knowledge, all could come into play. In my present situation, up on the mountain, I could make a decision, based on my fears or on other factors contained in my lens, to leave my guide sleeping by the mouth of the cave and make my way down the mountain trail alone. Or I could choose to trust him, and wait for morning. Regardless of which decision I made, because of my awareness of my separateness—achieved through the lens—it was now very clear to me that I alone was responsible for my destiny. I was terribly excited about being able to see all this. This vision of the lens provided me with a symbol for making sense of knowledge I hadn't even been aware that I was collecting over the years. I wanted to awaken Sen and discuss it all with him.

"Sen," I said. "Sen, are you asleep?" I went over to him and gently shook his shoulder.

"What do you want?" he asked, turning his head to face me. "Have you created another cat? A bird?"

I started to look for the words to explain what I was seeing. But then I backed away. I realized that Sen already knew about everything I had seen. To him it was common knowledge, and he had no time for it. "Never mind," I said, deeply hurt by the realization that I had no one with whom to share my discovery. "I'm sorry to disturb you."

Sen mumbled something I couldn't understand and went back to sleep.

I sat down and watched the world beyond the lens, and saw it all merge with memories, images, ideas and feelings that I knew belonged only to me.

As my companion slept, the shadows shortened on the ledge where I sat and I saw that the lens was not something new in my life. I saw it far more clearly than ever before, and that part was new and unfamiliar, but the subtle mergings of external sights, sounds, sensations, all seemed normal, automatic, even familiar to me. I realized that these things had always occurred—and the only difference was that now I could see them, could feel their shifts and mergings, their constant metamorphoses from one form to another.

I remembered many times in the past, all through my life, when I had also had brief glimpses into these basic truths about our ways of processing reality, glimpses never more substantial than the sun's reflection from a bright chrome strip on a passing car. I now saw why life really was not all it appeared to be. Rather, it took on meaning only as it merged with our images inside the lens.

Later that afternoon, as we made our way back down the mountain, Sen listened patiently as I related the story of what had happened to me up on the mountain. I wanted to know if he had experienced any of it. Were the things I had seen a shared reality? Had he seen any of it?

Sen shrugged. He was vague and elusive. He told me that the Indians believed that the place where we spent the night was a sacred spot, and that people often had visions there that changed their lives. I asked if he had ever had visions there.

"Oh, yes," he said. "That is why I sleep when I go there. When I sleep it does what it must do and I am not always jumping up and down thinking I have to do something about it." He laughed. "Unlike you, I am a very lazy man."

When I tried to get him to explain this to me, he said it wasn't important. He told me my Spanish wasn't good enough to understand him if he really tried to go into it. And his English wasn't good enough for him to even attempt it in my language.

He dismissed me with that phrase the Mexicans have for stopping all further conversation on a subject: "No me importa"—it is not important to me. "You went to the mountain and you saw what I promised you. I am a very good guide. I hope you will tell your friends about me."

I promised him I would.